Shooting the coup

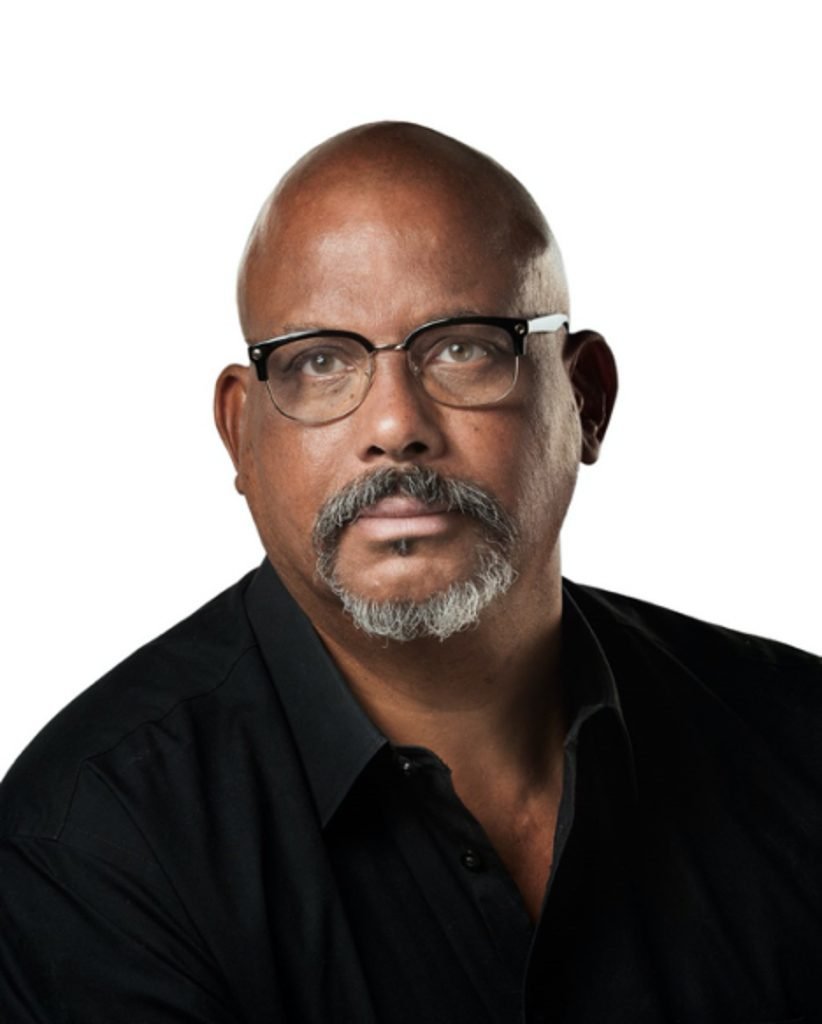

Photojournalist Mark Lyndersay recalls bullets, botched film – and lots of corned beef

ON THE NIGHT of the July 1990 attempted coup, writer and photographer Mark Lyndersay stepped out of the Trinidad Guardian building on St Vincent Street with his camera ready to shoot the unfolding events. Facing him was a man who pointed a gun in his face and told him "no pictures."

When he visited the Newsday offices he recalled the events of that day, and the days that followed, very clearly.

On the afternoon of July 27, the production manager was buffing Lyndersay over a design error.

"The fonts were all over the place. It was really bad. He was telling us that, 'You can't abridge this, you wasted paper,' and so on.”

In the middle of the setdown, the building rocked.

“We were like, 'Wow, earthquake.' And then somebody said, 'No, there was a fire.’

“We looked outside the window, which was, of course, looking north at the time from the Guardian– remember, there was no national library at the time, so it was a straight line to the old police headquarters as well as a direct line to the Red House – and we saw the smoke.

“And then we began hearing a 'pap pappappappap' – shots and so on."

Lyndersay went to a window that looked towards Edward Street and saw a car with its trunk open and people taking weapons out. Some wore bandanas, some wore masks.

"So I did the insane thing, which is of course to grab my camera, and I went out the back door, and a Muslimeen man pointed a rifle at me and said, 'No pictures.'

“I remember it very clearly. It is amazing how small the muzzle of a rifle is when you're staring down it. And I just shrugged and I said, 'Okay.'"

He had looked up and saw the late veteran journalist Terry Joseph on the street corner, doing a "wheel and turn again" gesture with his hands, and he decided to turn back.

The Muslimeen then shot up all the glass on the press-room side of the Guardian, on Abercromby Street.

LOST MOMENTS

Lyndersay went back inside, gathered his thoughts, and then went back to the north-facing window, put on his long lens, and began taking photographs.

It was dusk, and he shot two rolls of film of people running, people limping down the street, bursts of automatic fire and smoke coming out of the building.

But then he experienced his "great tragedy" of the evening.

"I gave them to a (late) photographer...and told him to process these two rolls of film so we could see what we have.

“And he processed the film in fixer (a mix of chemicals used in the final step in the photographic processing of film) because he was panicked and he was tipsy. Well, he was a heck of a lot more than a little tipsy. It was Friday afternoon and he was well into his cups.

“So what he brought me back, and he was actually trembling with fear now, was perfectly clear film. Because that's what happens when you run it through the fixer without developing it."

The photos were "irredeemably" ruined. Lyndersay sat back and looked at it and said "Okay then."

Then he got a call from the back gate that people were looking for him. It was reporters CaminiMarajh and Alva Viarruel from the Express (the other daily newspaper, and the Guardian's only competition in those days).

"And people were running about the place and there are shots and gunfire and smoke and so on and sirens wailing and they (Marajh and Viarruel) were saying, 'Can we come in?' And I was like, 'Well, it's not my house', but these are people I know so I said yes, and we went in."

By this time the army had arrived and wanted to take up a position on the roof. While they were setting up. Lyndersaywent up with Marajh and Viarruel.

"And I shot a photograph – by now it's well past dusk now, it's early in the night – of the flames rising up over the old police headquarters. And that went into the next day's paper.

“Actually, there was no paper the next day. There was a paper after that.

“It was the only time we skipped a publication entirely because there was simply no one there to run the presses."

He said the late Therese Mills, the editor-in-chief, the first woman to hold that position at a national newspaper (and later one of Newsday's founders), was really upset with him because he let "strangers" into the newsroom.

"And I said, 'Mrs Mills, there are people being shot at in the street.'

“And she said, 'Yes, yes, yes, but as soon as they can leave they must leave.'

“She was very stern about her newsroom."

After he had processed the second roll of film himself and Marajh and Viarruel had left, it was about 9 pm and things had started to quiet down. The army had secured the space.

Lyndersay, who had a motorcycle at the time, rode out from where he was parked in the Guardian basement.

"And it was really the most surreal thing because there were flames, there were the flashing lights and so on of police vehicles passing, all kinds of people walking up and down the streets, some of them carrying stuff on their backs, boxes – it was stuff they'd looted."

And so he went home.

SOMETHING TO SHOOT

Mills was in touch with the staff later on Friday night and they had decided to return at noon the next day.

On Saturday they began working on Sunday paper, which turned out to be "a very skimpy paper" that included Lyndersay's photographs.

"It was a very unusual time because you could leave, but you didn't want to really be out and about, because the whole set of circumstances was very uncertain.

“I think the scariest thing about it for me was at one point we went to a press conference. And I went with Carl Jacobs (later editor in chief) as the photographer, and a couple of other people came up and we were walking. And we walked to the Holiday Inn, which is now the Radisson, and I remember walking down the street and looking at all these little boys – they were men, they were in the army – with these enormous weapons (and) who were looking for something to shoot.

“And I have to tell you that I was more scared of them at that point than I was of anybody else.

Because they really wanted to shoot something. They were upset, they were annoyed, and I was not 100 per cent certain about their value judgments at that point."

Lyndersay said he had a particular concern as he had spent some time on the roof of the Guardian with the army and they had a "weapons-free" directive.

"They didn't have to account for bullets. They were just to shoot. And I saw bullets being discharged at a remarkable rate."

The army was shooting at "anything that showed themselves in the windows of the Red House." There was a window which came to be known as called "the hot window," where people would occasionally stick a gun out and fire. The Muslimeen shot up the north face of the Guardian building.

And how was working at the newspaper under these conditions?

"There was a lot of crawling around on the ground inside the Guardian because you could not take the chance of walking past the windows. There was also a lot of sleeping under desks.

“And the thing I remember most clearly is that there was a tremendous amount of corned beef."

He explained the Ansa McAl Group, which owned the Guardian, was aware there were people there who could not leave, and so went to warehouses and brought canned and tinned food for them.

"So many of us stayed there for days at a time and it was corned beef. Just corned beef. It was corned-beef casserole, it was corned-beef salad, there were corned-beef sandwiches.

“I couldn't eat corned beef for five years after the coup. Because it was just corned beef every single day."

IT'S THE JOB

During those days, the staff spent a lot of time waiting and trying to understand what was going on. Lyndersaywas in the Guardian newsroom, going out occasionally for press conferences, but there was very limited ability to move around.

"You couldn't walk up and down a street. You went to a place with a purpose, and the people were aware you were going to that place during that time. When it got locked down it got locked down very, very fully."

Asked if any family or friends expressed concern for his safety and putting himself at risk, Lyndersay said people had resigned themselves to the fact that this was what he did.

"This was an extreme version of what I did, but no one really said, 'Do you want to be doing this?'"

He said some Guardian staff members did not return to work either because they could not get transportor they were not inclined to. He recalled the Guardian ran for five or six days with about 20-30 per cent of its complement of staff.

"Because those were the people who were there and who could come out and who decided that they were going to be there."

But for him, "There wasn't any question about, 'Am I going to do this?' I wasn't terribly excited about it or was like, 'Wow, this is an amazing experience (and) I want to have this experience.'

“But I was there. It was my job. I was the picture editor, I was the most senior person in the photographic department. So this is what I signed up for. It wasn't precisely that, that I signed up for. But that was the job at the time."

Lyndersay said he was probably in shock during that time.

"I don't remember being scared. But I don't remember being terribly enthusiastic about the experience either. It was just, 'Okay this is the next thing we have to do. We have to process this film, we have to photograph this thing, we have to figure out what pictures we are going to use.’ You could lose yourself in the work in that way."

SURRENDER IN THE RAIN

His next clear recollection is the evening of the surrender of the Jamaat al Muslimeen. He went to state television station TTT (which had been taken over by the Muslimeen) and parked at what was then known as Casuals Club but was now an empty lot.

He walked west to Maraval Road and the rain began to fall.

"And it fell. And it fell. And throughout this process of the people coming out and surrendering, and laying down (their weapons) – all the weapons were in a big pile in the street – and photographing Abu Bakr, his lieutenants, people coming out, being patted down by the police, (and) led to a bus – I was soaked completely through. It was a major historical moment --but I was so wet. You feeling the tips of your socks wet and so on."

All the international media were there and were better prepared for the rain than the local media, as they had big raincoats and plastic sheeting for their cameras and so on.

How did he shoot in the rain? A lot of the time he held his camera under his shirt.

"But when it was time to shoot you shot. Because you had to take the pictures. Yes, you worried about the camera, but you shot."

He recalled receiving a call three years later from the Guardian – by then he had left– asking if he had any photographs from the coup for a commemoration of the event. He had taken two to three souvenir pictures, including one of the burning buildings and one of Abu Bakr surrendering with his hands over his head and being patted down.

Unfortunately, every one of his negatives had disappeared from the Guardian.

"It was the most remarkable thing. Within three years, they were all gone. Nobody knows what happened to them. They just disappeared.

“But all my work from that era is gone."

He said the only pictures that are left were pictures that he scanned and sent back to the Guardian.

TT NEVER THE SAME

Asked to reflect on those events 30 years later and if there was any justice for the victims of the attempted coup (about 24 were killed) Lyndersay replied that there was no justice.

"The people who died in that event never got justice. That's true enough.

"It was a social upheaval that I think at the time had to happen. I think it was extremely unfortunate that it did happen, but I don't know that there was a way to avoid that.

“I don't believe the country has been the same since then. And the idea that you can shoot somebody down in the street and get away with it, in my own heartfelt estimation, I think took root then. I think a lot of our crime and lot of what we are still grappling with and a lot of the hamstringing that has happened with our law enforcement has its roots back then."

He said the police service was "neutered" in that experience as the army took over.

"I think it was a humbling and humiliating experience for (the police)."

Now, 30 years later, new people are in charge of the police, with many who were involved then having since retired.

"But I still feel that there is a sense that law enforcement in this country has been on the back foot ever since. They have still been trying to recover and take a lead and take a forceful position since then.

“Up until that moment, there was the sense that the police were in charge. And then after that, it was very clear that it was possible for the police to not be in charge.

“And that is a very deeply troubling thing for a country to go through."

Asked if something like the attempted coup could happen again, Lyndersay replied that he had no idea.

"I think there are aggrieved people. It's possible that what we have been experiencing, in terms of crime waves and so on, is a kind of rolling experience of the same thing drawn out over almost two decades. We've lost a lot more people to senseless crime, murders (and) unexplained killings since then.

“I don't know that we can go back to what we were before. But I think we have to find a new way forward and a better understanding of the different classes that exist in this society, how they live together and how they don't live together. And finding a way to understand how we forge a modern nation out of these different interests."

Lyndersay said this is a very big challenge and is not effective as a policing engagement.

"But it's a social engagement that we're still very much flirting with. We're not accepting the fact that there are people who live in this country who live a very different life from the people who are even considered marginally privileged.

“And that's something I think we still have to come to terms with."

Comments

"Shooting the coup"