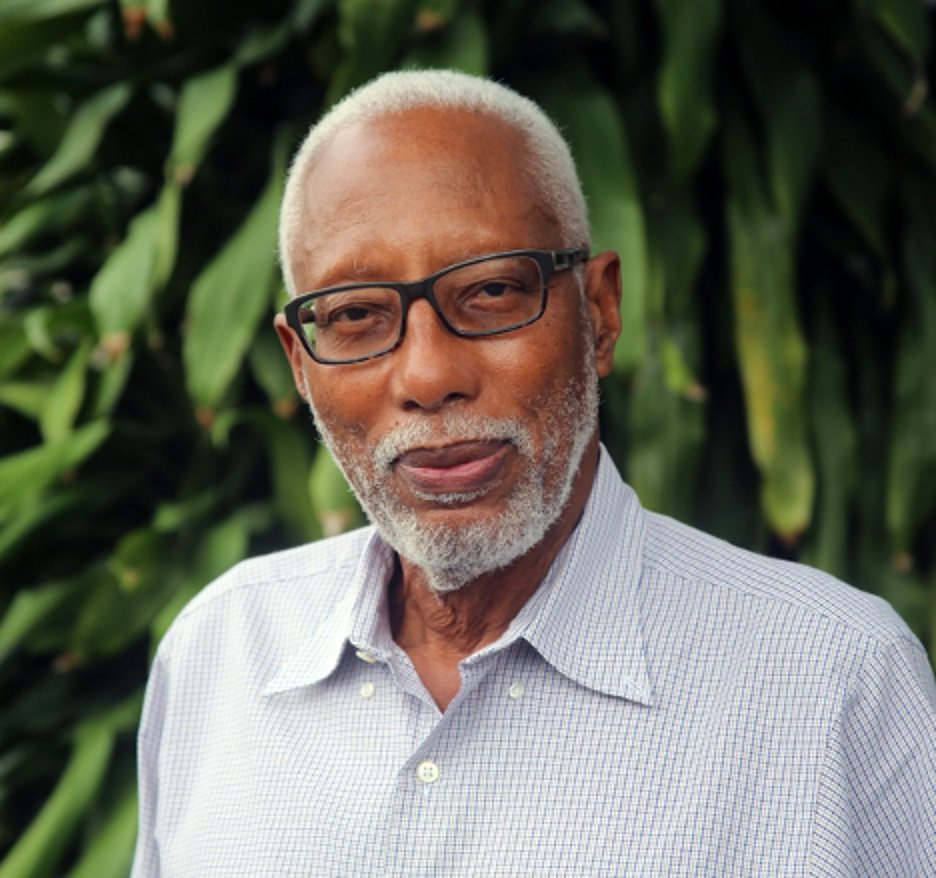

1990 hostage Selby Wilson recalls six-day ordeal: 'If the lights go out, kill them all'

WHEN 42 Jamaat al Muslimeen members took over the Red House, the seat of Trinidad and Tobago’s Parliament, they held 20 people hostage for days in inhumane conditions. At one point the insurgents began discussing a plan to kill them all.

On the afternoon of July 27, 1990, Selby Wilson, finance minister in the National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR) administration, was in the Parliament chamber. He wanted to be present for the debate on a number of corruption-related issues, including McDonnell Douglas Aircraft, petroleum company Trinidad Tesoro and former People’s National Movement (PNM) minister John O’Halloran.

He had missed the morning session – he was preparing for a trip that weekend for a ministers of finance meeting in Jamaica– but remembers walking to Parliament for the afternoon sitting around 3 pm.

“And it wasn’t long into the session we heard the commotion. People were entering the Parliament shooting. They were actually shooting. Firing shots. It was fortunate that only one person died in the reckless firing of guns in the chamber.

“I remember distinctly that as I heard the shots being fired I took the floor of the Parliament. I was sitting next to (minister of social development and family services) Gloria Henry, who stood up rather than go down. And I pulled her down.”

The men who stormed the Parliament were led by Jamaat second-in-command Bilal Abdullah. After they came in they started walking around and asking people who they were.

“When they got to me and they said, ‘You are Mr IMF (International Monetary Fund).’”

As finance minister Wilson had taken the decision to go to the IMF to assist the country out of the deep recession of that time.

“And with that they slapped me about the head. Hard enough to affect my hearing. And they hoisted me over the banister of the seating arrangements of the floor. They put my hands behind my back, and using the plastic tie (tied my hands and) pulled it. And they said, ‘Is that tight enough?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’

“And they yanked it one more time. So I had a blister on my hand for quite some time after.”

As he lay flat on the floor with his hands behind his back, what was going through his mind?

“I just felt it was an act of fate. I consigned myself to the Lord and said, ‘You do what with me whatever you will.’

“So I didn’t feel scared, I didn’t feel anxious.

“But I knew it was a serious act and it could probably result in the death of people.”

He spent all of Friday night lying on his stomach with an insurgent poking a gun into his back.

“If anything happen you will be the first to go and we throwing you through the windows,” the man kept telling him. Wilson thought the threat was a serious one.

He heard the insurgents speaking to Prime Minister Arthur NR Robinson and National Security Minister Selwyn Richardson, though he could not make out the entire conversation. They were apparently trying to persuade Robinson to tell the troops not to attack.

“And he did the opposite. He in fact gave the command to ‘attack with full force.’

“And then I heard a shot. I didn’t know he (Robinson) was shot until afterward. I actually thought Selwyn Richardson was shot dead, because when I looked across, Selwyn was lying on a bench totally covered in a white sheet. And I thought he had died.”

Richardson, however, had been shot together with Robinson and was lying on the bench recuperating.

Wilson later learned that NAR MP for Diego Martin Central Leo Des Vignes had also been shot, in the heel, likely during the indiscriminate firing when the Jamaat entered.

When negotiator and Anglican priest Knolly Clarke arrived later, he arranged with Abdullah for Des Vignes and other wounded, including Robinson, to be taken to hospital. Des Vignes later died.

Abdullah also agreed to free Planning and Mobilisation Minister and NAR deputy political leader Winston Dookeran, “because they had a theory that Dookeran should take over and Robinson should surrender.”

But the rest of the hostages remained for the six days. On Sunday afternoon the Jamaat brought other hostages into the chamber, including a policeman, acting Sgt Raymond Julien, and deputy mayor of Arima, Martin Thompson.

“Part of the story that stood out in my mind is that Bilal, in the negotiating rooms, had agreed to let us (hostages) out before the six days. It was probably the third day or so.

“(Opposition United Labour Front MP) John Humphrey indicated to Bilal not to trust us. Get it in writing. And I think this is where the amnesty came in.

“So we stayed in there beyond that time because of that interjection by Humphrey.”

What did Wilson think of Humphrey’s interjection?

“Very reckless. It was really a reflection of the character of people, in my mind.”

He said as a result, the hostages spent a further three days under very trying circumstances. They were not given any food except on the third day when the insurgents brought them some caviar from the kitchen. Wilson refused to eat, as he did not want to get sick. A six-day fast was not unusual for him. He does not know if any other hostage ate.

He was given water during that time, but very little and irregularly.

“The conditions were very bad. We couldn’t even ask to go to the toilet. We urinated in tumblers. The women went behind the Speaker’s chair to urinate in a bucket. Very embarrassing. Very dehumanising.”

Wilson was next to Mervyn Assam, then a high commissioner, who had gone to Parliament to get a licence to set up the Clico Investment Bank, and deputy Speaker Dr Anselm St George, who “was in a state.”

“By the end of the six days, he had a rash down his legs from urinating on himself.”

The stench was very offensive and the treatment of St George and the other hostages was all part of the dehumanisation.

He had limited conversations with Assam and St George, each mostly enquiring how the others were doing.

The hostages also had brief conversations with the insurgents. One came up to Wilson to say he was “Morris from Point Fortin,” and knew him.

Since the Jamaat is an Islamic group, during the hostage situation, the insurgents would chant prayers. Wilson joined in with them after picking up what some of what they were saying.

“Prayer is prayer.”

He recalled taking out his chequebook and writing out instructions on the back of a cheque authorising his wife to have full access to his account in the case of his death.

“I still have the cheque. It was effectively my will.”

Once the insurgents allowed him to make a call to his sister and wife to tell them he was all right. His wife was understandably tense and nervous. He also had two young children at the time, one six and the other 11.

“I was thinking a lot about them.”

On either Friday night or Saturday night Abdullah thought the army was going to attack the Parliament. He instructed his men to take all the hostages to the centre of the chamber. Their hands were tied behind their backs and they were made to lie on the floor.

“And he told his men to take up their positions with the guns on ready, with instructions that if the lights in the Parliament went off, to shoot us first and then they (would) defend themselves.

“And his rationale for this was the first thing (the army) do is turn off the lights and send in flares to disorient them. And therefore his instructions were, as soon as the lights go off, kill the hostages and then they would defend themselves.

“So I was very grateful that T&TEC (TT Electricity Commission) didn’t have a blackout that night. Because I think there would have been a bloodbath in there.”

Eventually some of the insurgents, who were armed with large automatic weapons, began getting irritable. One of them started walking around in a daze and Abdullah asked minister Dr Emanuel Hosein to attend to him. The insurgent was in such a state that he had to be tied down. Wilson believes he had some type of depression or psychotic state.

“If it hadn’t been done he would have triggered off and killed a few people.”

Hosein attended to wounded insurgents as well and hostages, including Robinson, before the latter was released. He was taken out of the Red House precincts in a wheelchair, almost blind from glaucoma.

Wilson recalled that the only PNM MP in the chamber at the time of the attack was Muriel Donawa-McDavidson, who escaped on the first day by running down a corridor.

On the sixth day, and after negotiations, the hostages were released.

Donawa-McDavidson’s driver had been shot dead outside the building. When they were leaving the Red House, his body was still there.

“The stench was high. We had to walk past his body to get into the buses.”

Wilson had survived six days without breaking down emotionally. But when he came out, people started greeting him and sympathising with him, including some of his colleagues who had not been in the Parliament at the time. They told him he was fortunate to escape.

“I realised the calamity of the situation. I couldn’t hold back my tears. Although there were no tears in Parliament.”

He and the other hostages were taken to Camp Ogden at Long Circular Road, St James, but they were not seen by any medical staff at that point. They were later transferred to the Trinidad Hilton, which was being used as a base.

The Jamaican government offered to put up the hostages who felt they needed a break outside Trinidad. Wilson took up the offer and spent a week with his family at a Sandals resort.

“It was good to be there and out of the environment.”

While in Jamaica he saw some TT news but made no deliberate effort to watch it.

“It was part of my recovery.”

Some time after he returned to Trinidad he went back to work as finance minister. He was assigned a police officer to guard him for two months after the attempted coup.

“I was fortunate (the experience) had no lasting effects on me apart from the physical damage.”

After his release, he had to be treated for a buzzing in his ears caused by his assault. He was prescribed medication and it eventually went away. He said there was no psychological damage and he never underwent any therapy; nor was any offered.

Wilson said it was striking that both ULF leader Basdeo Panday and PNM leader Patrick Manning were absent at the time of the attempted coup. He recalled that both were very callous in their responses to the incident. Panday made the famous comment, “Wake me up when it’s over,” and Manning said it was “between the NAR and the insurgents.”

“It did not reflect the national concern for our democracy of the gravity of what was taking place. They are at least guilty of treating it flippantly.”

He recalled that before the attempted coup the government was demonised.

“Almost as if government punishing the population.”

Wilson said as he became finance minister in 1986 there was the challenge of a literally empty treasury.

He said the Jamaat leadership has always been encouraged by different levels in society and that empowered them.

“They believed they could overthrow the government."

Wilson said there was a legal argument that the president (Noor Hassanali) did not grant an amnesty to the insurgents under duress because he was not in the Parliament, but it was an argument he found difficult to accept. Emmanuel Carter was acting president at the time.

“If the President has to think of a number of lives in Parliament to be saved, he must be under some undue pressure.”

He said there was also a technicality that the insurgents could not be tried twice.

Wilson noted that some people believed the Jamaat’s escaping any real punishment had given growth to the crime which the society has been experiencing.

“That may very well be so. If you do acts and get away, that encourages that behaviour. It becomes pervasive.

“Even now criminals are getting away. That is something that needs to be addressed in the justice system which has not yet been addressed. We have similar issues (today) of justice being delayed or denied.”

Did the hostages or those who were killed, estimated at 24, ever receive justice?

Wilson said the families who lost loved ones should have received some kind of compensation. As for the hostages, he said they might consider it a risk of the job they did.

He said an incident like the attempted coup could happen again and possibly in a more undisciplined manner, especially with the proliferation of high-powered weapons.

“The Jamaat at least were a little organised and controlled.”

Why is there no major annual remembrance of this dark time in the country’s history?

Wilson said it is because of the lack of maturity of TT’s politicians.

“They are not strong enough to say something to have it treated more seriously and given the prominence in our democracy. It is a similar lack of maturity where projects between governments are stopped for no real reason.

“If one thinks that it was not really an attack on the NAR government, but on the democracy of TT, then we will get the seriousness of the attack. This has not been appreciated by any political party.”

In the aftermath of the attempted coup, politicians made comments like “they too wicked,” “they look for that” and “the party doing wrong things which caused it.”

He said successive governments have only paid lip service to commemorating the attempted coup, and for many years only the NAR commemorated it.

He described the looting and burning that took place as a disaster, recalling walking down Frederick Street and seeing the damage. He wondered if this was not the natural reaction of people who had been encouraged by those who attempt to lead. He said this “I have to get back at them” political strategy was essentially still in play today.

“It was very pronounced under Robinson’s leadership, by both the PNM and the ULF. They painted him as a Tobago man who doesn’t have Trinidad at heart.

“But he served the country well. He had flaws. Which us of has no flaws?”

He is surprised that 30 years has passed so quickly since the attempted coup.

He stressed that there must be respect for those who offer to serve as leaders of the country, and the people who think differently should offer themselves to serve.

Wilson has long left politics behind and is a telecom strategist at the Caribbean Telecommunications Union and consulting partner at Financial Resource Management.

He has no regrets about serving the country from 1986-1991.

“In spite of the (attempted) coup. It was part of my own maturity, my development. It conditions my thinking in what needs to be done. I view the experiences as to what I could benefit rather than gripe about it. That helped me maintain my mental stability.”

Comments

"1990 hostage Selby Wilson recalls six-day ordeal: ‘If the lights go out, kill them all’"