Who killed my mother? Daughter still seeks answers 30 years after coup attempt

On Friday, July 27, 1990, the Jamaat al Muslimeen stormed the Parliament, Trinidad and Tobago Television and Radio Trinidad. They bombed the police headquarters, took hostages, and demanded the Government and military surrender. They demanded that the prime minister resign and their leader be made Minister of National Security, and for elections to be called within 90 days.

This resulted in a standoff that lasted until their surrender six days later

For the next few days, in print and in our online edition, the Newsday looks back at those events of 30 years ago, the effect they had on individuals and society, and the trauma they left behind.

Afeisha Caballero cannot remember her mother’s face.

One stranger can’t forget it.

Official records say 24 people were killed in the six days of the 1990 attempted coup. Parliamentary clerk Lorraine Caballero was one of these casualties.

For 30 years, Caballero’s daughter has wondered who killed her mother.

But a recent interview with an insurgent who was at the Red House during the attempted coup may reveal key details of what happened.

Speaking with Newsday on condition of anonymity in June, the insurgent recalled the moments leading to Lorraine Caballero’s death.

He said he struggled with a guard over a pistol in the chamber of the Red House during the Jamaat al Muslimeen’s assault on the Parliament.

“He throw his gun on the ground and I bend down to take up the gun and I heard a noise behind my back, but I didn’t take it on.

“But behind him had a woman. When I raise up I see the woman on the ground bleeding…God knows best. I bend down to pick up his gun and the woman get shoot.

“Years after, I hear they talking about this woman. She was shot.

“I don’t know if she's alive or she died by the Jamaat al Muslimeen. I couldn’t never forget that woman face.”

Lorraine Caballero, 34, was one of two women shot and killed during the insurrection.

Afeisha Caballero, who was only two at the time of the attempted coup, did not even say goodbye to her mother as she left the family’s Champs Fleurs home for the last time 30 years ago.

Speaking with Newsday earlier this month at her Mt D’Or home, metres from where she grew up, Afeisha said while the insurrection means different things to different people, she will always remember it as the day her life was torn apart.

While she was too young to remember the insurrection itself, Caballero said the absence of a mother growing up is a painful reminder of its lingering legacy.

“My father said she left to go to work one Friday morning, and my eldest brother, Akee Caballero, asked her to stay at home. She said she couldn’t stay home because she had to collect her salary as it was month-end.

“She went to work and never came back home. The last time we saw her was in a body bag.”

Afeisha said her father and brothers, nine and seven, were not given any official notification that Lorraine had been killed, and were left to wonder what had happened to her as chaos engulfed the streets of Port of Spain.

Her father said no one contacted him at that point in time. He was just watching television when he realised that Port of Spain was under attack, the Red House was under attack – and she didn’t reach home as yet.

“Then when Saturday morning reached and she still didn’t come home, that’s when he realised that something had to be wrong.”

The Caballero family eventually learned of Lorraine’s death days later, when they had to identify her body among a number of others who lost their lives in the insurrection.

Afeisha, still a toddler, was unaware of the tragedy. She was raised to believe her paternal grandmother was her mother.

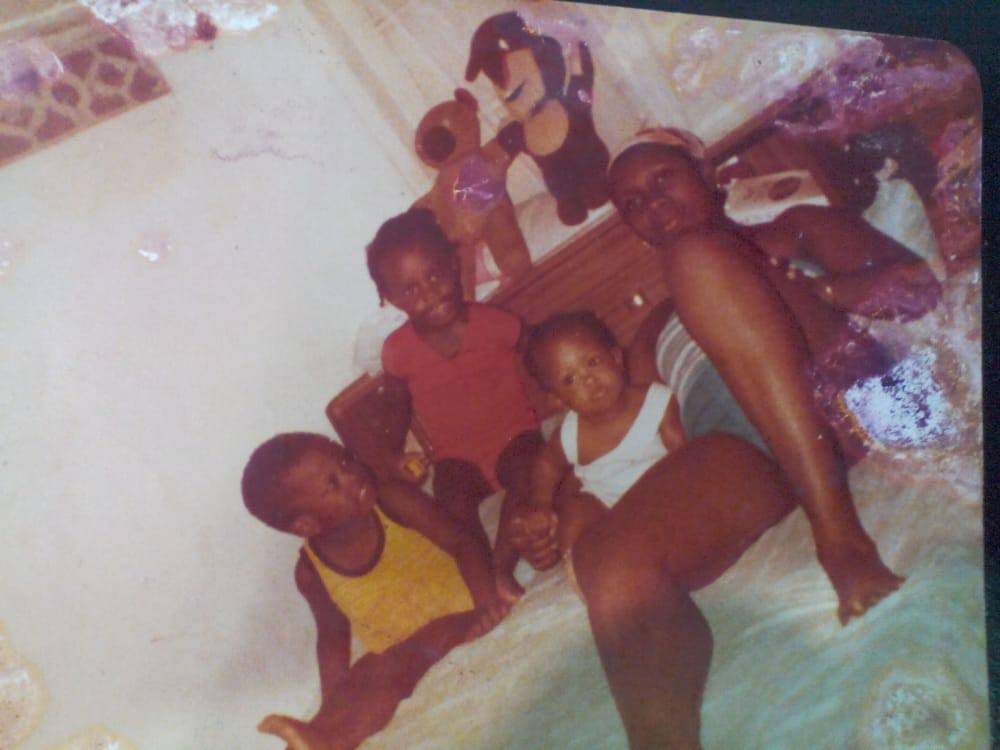

PHOTO COURTESY AFEISHA CABALLERO -

She said the truth was revealed when she was 11. She was at the neighbourhood parlour – and the shopkeeper explained what happened.

“The lady in the shop asked me what I came for and I told her what my mummy sent me for and she said, ‘You know your mummy died, right?’

“I said my mother is alive, she was at home – all this time I was referring to my grandmother as my mother.

“But the shopkeeper said, ‘Your mummy got corn and died.’

“I didn’t know what she meant so I stopped eating corn for a while.

“My father wasn’t living with us at that point in time, but when I did eventually see him, I asked him about it and he finally admitted that she died in the Red House.

“It was around that time I learned that I had brothers also, because I didn’t know about them either.”

This revelation turned Afeisha’s world upside down. She now had to mourn the mother she never had the chance to know.

It also gave rise to conflicting emotions about her family. She still finds it hard to describe her feelings about the relatives who kept this secret from her.

“I’m here with them because they’re the only family I know.”

The emotional turmoil did not end there. She was called to testify at the commission of inquiry in 2012, when she recalled the wounds her mother’s death inflicted on the family, wounds she said have never properly healed.

The commission found that Lorraine Caballero's death "seems to have greatly contributed to the dysfunction of her family. It is possible that the family lost her maternal guidance and influence as stabilising factors." Afeisha testified that afterwards her father took to drink and drugs. He died at 51. Her two brothers "manifested anti-social behavioural traits." Her brother Akee was one of three men shot dead by police in Morvant in 2009.

Over the years Afeisha said she has done her own research to better understand the cause of the insurrection and what would lead men to take arms against their country.

But while she may be better informed, the reasons are still unclear to her.

“It was inexcusable what they did. Thirty years after, I want to know what it was over. Why did she (my mother) have to lose her life?

“I still don’t know what it was all about, if it was over land, or if it was about some old talk.”

There is another question over whether her life might have turned out differently.

Jamaat leader Yasin Abu Bakr went to TTT and said the women and children were to be released.

“I was wondering if he meant those at the Red House as well. Up to this day I don’t know who was the person who shot her, or why.”

As she tried to make sense of it, she needed to speak to one man to gain her a sense of closure – or at least a better understanding.

Despite her apprehensions about him and his organisation, Afeisha felt she had to meet with the man who masterminded the insurrection.

“Throughout the entire process of the commission of enquiry, the only person whose take I didn’t hear was Mr Bakr, and that was because he told the commission that he also had a matter before the High Court at the same time.

“When I was much younger I went to the masjid to see him and talk to him but he didn’t have time. I went again a couple of years ago, coming closer to Eid, but he wasn’t there at the masjid. I left a message, but he never contacted me.

“I want to speak with him face to face. Just to get some peace of mind. And I think he’s the only person that can give me that.”

Young and filled with frustration, she was angry at Bakr, the system and the country she felt failed her by not being able to protect her mother and convict the man who orchestrated the coup.

Now, while Afeisha is still deeply pained, her thoughts about Bakr are more settled. She prefers to “leave him to God.”

The same cannot be said about her perception of the criminal justice system. She feels one of the insurrection’s biggest lessons was the weakness of the courts.

“One lesson this taught me was that you can get away with murder in this country once you have the right connections.”

While the attempted coup is still vivid to those who survived it, Afeisha believes the insurrection is just another fading memory in the national consciousness of TT, owing in part to misinformation and the absence of a national discussion on its effects.

Recalling a heated argument she had with a man over how many people died, she said it was just one example of how many people were misinformed about the grim truth of the 1990 attempted coup.

“I remember I was at the hospital where a gentleman told me, ‘Where in the world do you know a person staged a coup and two people died?’

“He said the only two people who died was a police officer and some other person. I told him that my mother died as well, and the man was arguing with me and I was getting so angry. A lot of people died.

“People still don’t know what actually happened.”

While she feels people should do their own research into the insurrection, Afeisha also believes the government has a responsibility to honour the memories of those who died through a national day of remembrance, something she hopes is done sooner rather than later.

For all the pain, she does not shy away from the topic, especially when her sons, Malachi and Nathaniel, ask her about what happened to their grandmother all those years ago.

“I tell them that was the day my life was torn apart. As much as God is the boss and he knows best, I still feel that things would have been different if my mother was around. She would have pushed me to get out of the ghetto.

Afeisha, a CEPEP worker and lives near the site of her family’s home in Champs Fleurs, which burned down years ago.

“I’m an adult now and I can move on and move out – but move out where? It doesn’t make sense that I leave from one area and go to another area, and the way that society is going I may not survive on my own.”

Afeisha’s story is a reminder of the dangers of violent uprisings.

Armed rebellions often involve the loss of innocent lives. While history is seldom black and white, innocent people with no loyalty to either side of a conflict can be collateral damage in violent clashes.

It also shows the lifelong impact that the 1990 coup attempt has had on the lives of ordinary people who were guilty of nothing and who were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The attempted coup never really ended for Afeisha Caballero. She feels the pain it caused her every day of her life.

Comments

"Who killed my mother? Daughter still seeks answers 30 years after coup attempt"