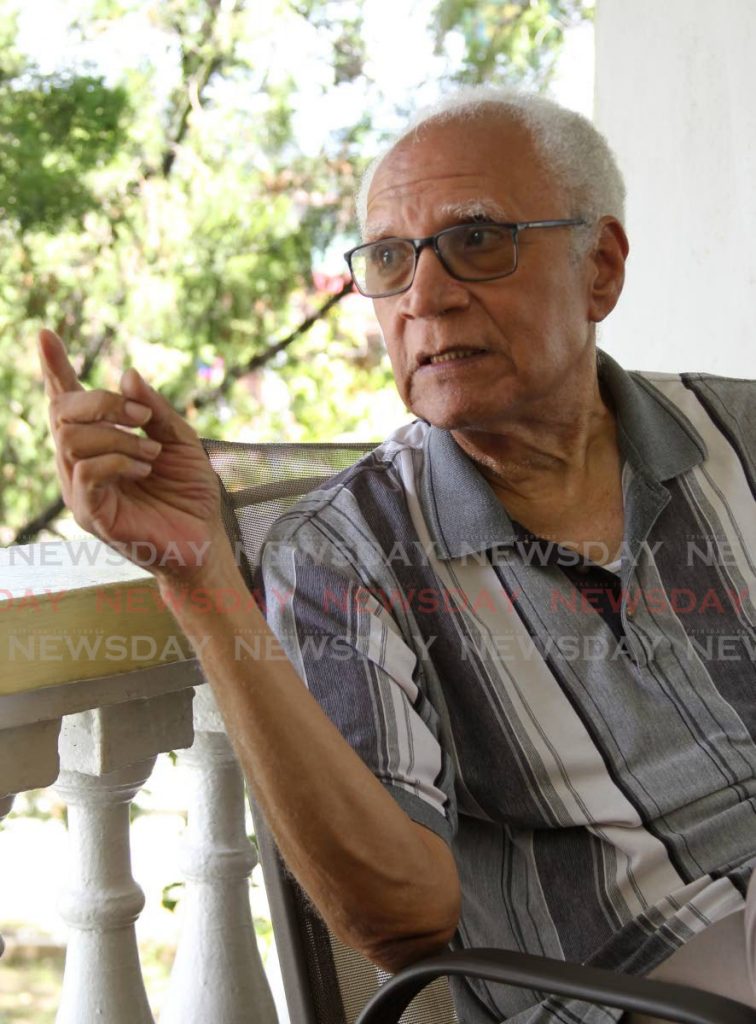

Jones P Madeira: Son of Arima soil

JANELLE DE SOUZA continues Sunday Newsday’s reflection on the career of Jones P Madeira with an account of his childhood and early entry into media.

Jones P Madeira’s early life was not a stable one.

He recalls his mother, himself and his three siblings packing their bags and moving to various parts of Arima every six to eight months. Why? “Because my mother did not suffer fools gladly and refused to be humiliated by anyone,” he told Sunday Newsday.

Born in Arima, Madeira, 76, said he did not remember any time before 1950 but he knew they lived in Sangre Grande for a while as well. He said their longest stay at any place was four years, when they moved into a large dilapidated house in central Arima: Cocorite Road, to be exact.

This latest location was an entrance to “over the bridge,” where new habits and more permanent friends were found. Among these new acquaintances was the Choo Ying clan. He played dolly house with his sisters and the Choo Ying daughter, as well as spear-fishing in the Arima River with the boys.

The new neighbourhood also brought them near the Princess Cinema just up the road, where Madeira feels he saw every western movie ever made. The cinema, incidentally, is where he got his first job: six cents for cleaning the cinema.

His mother, Gertrude, now 97, found the house through an acquaintance who told her they owned a house and were not doing anything with the property, so she and her children could stay there. The top of the house was made of wood which had rotted so they lived on the ground floor and slept on the dirt floor, with sheets to keep them warm. He recalled that sometimes when it rained, the roof leaked, and they had to move to another part of the floor to sleep.

Sleeping on the floors of houses or sharing small homes with numerous people was the norm for him by that time and the pattern continued for many years.

One good thing about those times, however, was, Madeira says, people did not see race. The profile of the area was a mixture of today’s TT demographics and the names of the people told the story: Madeira, Choo Yings, Ramsumair, Tota, Oliver, Pierre, Rahael, Moufidy.

Madeira’s father, Felix Duke, was a police officer whose wife had died. He was from the Duke clan, essentially Tobagonians from Delaford, which includes politician and labour leader Watson Duke.

He was a police inspector who became head of the criminal investigation department in San Fernando for a time. Madeira described him as a gruff person with an overwhelming presence. He was afraid of his father until he spent some time with the man when he was older.

He said in those days times were hard, mostly due to the country recovering from World War II. They were among the poor who had to battle the many shortages, but a Chinese shopkeeper, Mr Kom Tong, and his wife always ensured some supplies to help them survive.

-

“I never found it difficult. We had grown so accustomed to the hard times that if we had to do something that was a challenge, we were better prepared. For instance, I remember us having breakfast, but I don’t remember getting a steady lunch or dinner. But Gertrude, through her hard work and dedication, always ensured something was always there.”

One of his earliest and most poignant memories is of getting diphtheria at the age of four. Diphtheria is a bacterial infection that affects the skin as well as mucous membranes of the nose and throat. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website says it can lead to difficulty breathing, heart failure, paralysis, and death.

Madeira spent about three months in isolation at the Port of Spain Colonial Hospital. His mother would leave Arima to visit him, but had to stand in the courtyard below his room. The nurse would take him out of a crib and stand with him on a balcony to look down at his mother.

“I remember that as a heart-wrenching thing, to see her, and she would wave, and I would be put back in the crib. If the visit lasted five minutes it lasted long, but she would come almost every day.”

Following the girls to school

At one of his numerous homes, there was a neighbour, a shoemaker, Peter Attai. Attai liked to hear Madeira talk and would come from work and call the four-year-old over.

He would have magazines, newspapers and other reading material spread out and would read for Madeira. And in this way, Madeira taught himself how to form letters.

Madeira and his family once again moved, not too far from Attai, to live with “Tant” on Sanchez Street. She took them and others into her one-room home, in which about ten people, mostly girls, slept on the floor.

“Things were so bad sometimes that now and then you would move and you would hear a squeak. And that squeak would be a mouse that you just mashed.”

However, the building was next to the Arima Boys’ RC School, with the Girls’ RC School less than a block away. Madeira was always enthusiastic about going to school and so one day he followed his female adopted cousins there.

He recalled sitting quietly at a desk when the teacher noticed him sitting with the girls. However, there was no one to take him back home so the teacher kept him – and he continued to attend the girls’ school. In fact, at the end of term, the teacher gave him a copybook and pencil and when school reopened, he kept attending the girls’ school.

-

He did so until he was five, by which time they had moved again.

“I was so afraid of my teacher, Harry Cumberbatch, so much that I made biche (played truant) for a couple weeks. I got the worst licking from him and those at home.

"The event made me beg to go to the Arima Boys’ RC and it is there I settled under the hand of teachers like Mr Sulan Assue and Vicor Mitchell.”

Years later, he wrote his post-primary examination and, around age 14, began attending Holy Cross College.

A love of broadcast

Madeira’s family could not afford a radio, but a few of his neighbours and some of the shops in the area had them. While he liked the music, he mostly enjoyed the sound of articulate people talking to him through the speakers.

Madeira recalled that the Trinidad Broadcasting Co Ltd’s Radio Trinidad used to join the BBC news broadcast and he was fascinated by the voices of presenters John Wing and Peter King, who became his favourites.

“I would listen to the quality of the announcers’ voices and the words that were being said. I remember thinking, ‘I would like to do that.’ Little did I know that, in several years, I would be originating that type of broadcast, that I would be one of those people on the BBC.”

It was not only BBC presenters who made an impression. Even at the age of nine or ten, the voices and presentations on Radio Trinidad, including Bob Gittens, Peter Minshall, and Frank Pardo, fuelled his desire for information.

When he was around 15, Holy Cross was having a concert as a fundraiser for the Santa Rosa RC Church. Being in charge of the project along with fellow student Frank D’Abreau, who himself was a performer, Madeira wanted to publicise it on the radio.

He wrote a letter to JC Mc Donald, who had a Saturday programme on the very popular Voice of Rediffusion, and was invited to talk about the fundraiser on air.

Excitedly, he asked his mother for a new shirt and 36 cents. He got another 36 cents from a neighbour, and that allowed him to travel to and from Port of Spain, and buy a rock cake for lunch.

As he entered the station he immediately noticed, and still remembers today, the fresh, crisp smell and the welcoming lobby. Mc Donald met him there and escorted him to the recording studio, where he was promptly “blown away” by the set-up and interviewed about the fundraiser.

“After the interview he said, ‘You know something? I like your voice. It sounds good on the radio. Why don’t you come on a Saturday and sit down with us and we’ll have you be a part of the programme?' And I said yes.”

Every Saturday for the next two or three years, he targeted that 72 cents in order to be part of the 1 pm Saturday programme – for which he was not paid.

He loved it and decided to build a makeshift studio at home, where he had gone to assist a sick cousin, who was looking after the property for an aristocratic family, the Paredes. The woman who bought it, Elaine Miranda, a retired postmistress, lived alone and asked whether he would come and stay there. He gladly agreed, and spent the rest of his teen and early adult years there.

“I borrowed a tape recorder from the priest at Holy Cross College, and I set up a little studio. And if you passed by at two, three, four o’clock in the morning and looked upstairs at the attic, you would see a light on. That would be me talking, taping, listening back, re-recording, and reading from the newspapers. In some cases I liked hearing myself and at other times I would hate it, but I kept going.”

And so years passed with Madeira as an unpaid amateur announcer. But he had developed skills.

When the National Broadcasting Service (NBS)’s Radio 610 was formed, some of the Radio Trinidad announcers moved to the new station. Dave Elcock in particular encouraged him to make the move and he did. As an amateur announcer he joined others on a programme called SatTeen (Saturday Teen) session from 9 am-12 pm every Saturday.

Then, in 1963, at 19, Madeira became a trainee reporter at the Guardian.

“I had no aspiration to become anything other than a broadcaster, although I was encouraged by one of the Holy Cross Dominican Irish priests, Fr Francis Mc Namara, who took a chance to seek out a position for me at the Guardian. I got the job – and it turned out to be one of the best decisions I made.”

Madeira’s initial beat was the magistrates’ and high courts, and he would tackle politics and general reporting also. His performance earned him a position at the Guardian’s office at Piarco Airport.

“Piarco was awesome and inspiring. I interviewed and wrote stories on almost every head of government of the Caribbean at that time, and I enjoyed in particular a special relationship with Dr Cheddi Jagan, who eventually became president of Guyana, and also Forbes Burnham and Shridath Ramphal.”

After a few years, he resigned to become a public relations assistant at the Canning’s Group of Companies, but returned after 18 months. He spent less than a month at the Guardian this time around, because his life-long dream was about to come true. He had applied for and was offered a job on the staff at 610 Radio in January 1970.

There, he made his mark in broadcasting covering the demonstrations and turmoil at the time of the Black Power Revolution and the resulting state of emergency.

A year later, in September 1971, when he was 26, Madeira accepted a training fellowship at the BBC, the organisation he had admired since he was a boy. He was amazed by the fact that he was at the BBC. At first, he was rattled as he was not accustomed to so many people being in the studio with him. At least seven people were “in his face,” and he stumbled a few times.

However, after the fellowship, he was offered a job there and so he returned to TT, married his girlfriend Melba, and went back to London with his wife. He soon became a producer with the organisation’s Overseas Regional Services and remained there for two more years.

By that time, he was ready to go home to TT and rejoined 610 as a senior producer.

However, during his years at the BBC he had made a contact at the Commonwealth Secretariat in London. He received a letter saying he had been recommended for a media relations adviser position at the Caricom Secretariat in Georgetown and was later offered a two-year contract. He stayed there for five years, from 1976-1981.

After that he held numerous positions, including the first full-time secretary general of the Caribbean Broadcasting Union, editor in chief of the TT Guardian, editor of the Independent newspaper, manager of News and Current Affairs and Caribbean Relations at Radio Trinidad, head of news at TTT, member of the board of the Caribbean New Media Group (CNMG), public relations manager at Nipdec, communications manager at the Ministry of Health, information adviser to the Caribbean Epidemiology Centre (CAREC/PAHO/WHO), and court protocol and information manager of the Judiciary.

In 2014, he became editor in chief, and then executive editorial consultant at the TT Newsday. In 2018, he received a national award, the Chaconia Medal (gold), in the spheres of public service and journalism.

And so Madeira rose from a small beginning, grabbed opportunities, and grew from strength to strength to become one of the most respected journalists in TT.

Comments

"Jones P Madeira: Son of Arima soil"