Digital campaigning, 2020

BitDepth#1256

IS TT ready for a virtual election campaign?

A significant technology engagement is likely to be part of the voter push over the next five weeks as political parties – the two majors and smaller independents – work to make their messages resonate.

The walkabouts have begun, with candidates strolling the streets of their constituencies hoping to press home a message of presence during a time of covid19-mandated distance. But there is a limit to how much in-person engagement can be considered.

Police can't raid a bar and charge 61 people with breaking restrictions on public gathering, then turn a blind eye to groups assembled to hear political speeches or festive parades in the streets fuelled by hastily composed campaign songs.

If physical space is restricted, virtual vistas are essentially unlimited, but political parties haven't proven particularly effective at using online media to articulate messages that appeal to young voters.

Online campaigns have tended to be either push advertising, flooding ad slots with uniformly forgettable messages featuring smiling politicians, or thinly veiled mudslinging, using sock-puppet accounts and vocal supporters to target opponents with invective.

Both approaches discourage youth participation in the polls and reinforce voter apathy towards the prospects available on the ballot sheet.

Both major parties have aggressively tried to offer up new faces, purging stale and uninspiring prospects who have aged out of relevance in favour of candidates that look more like most voters.

According to indexmundi.com, which tracks global demographics, in 2018, 69.66 per cent of the TT population was between 15 and 64, with a massive 44.99 per cent in the age range 25-54.

That's more than 540,000 voting age adults who matured when it was possible to become digitally capable.

That number is also likely to be a hefty slice of the 734,792 people who voted in 2015.

Any sensible political party is going to want to talk to that group, but reaching them will be a challenge.

Their collective presence on social media and the wider internet, in my experience, suggests they are not particularly receptive to broadcasts, favouring one-way communications only as chew toys for private conversations on issues they find relevant.

Of the 41 candidates offered by the PNM, at least 23 are young people with minimal public political histories. On the UNC slate, 19 of the 31 candidates to date might be similarly classified. Almost half of the major parties' candidate rosters are still to be introduced persuasively to the electorate.

Many experienced politicians find it difficult to engage with digital natives who are unwilling to grant respect until it has been earned, often expressing such disregard with casual incivility and a tendency to backchat.

There are also significant tribal nuances attendant to participating on different social media platforms. There is, for instance, no communications strategy that straddles the engagement divide between LinkedIn and WhatsApp.

To reach voters in 2020, political parties must master, in short order, the capacity to host multiple micro-conversations across widely differing digital hearths by replacing traditional rally-style bluster and podium pageantry with effective and meaningful online engagement.

Beyond that, parties must embrace a fundamental shift in communications models that deprecates top-down declarations in favour of vigorous discussions that border on brawls.

There are 32 days left for political parties to find a digital path past covid19 restrictions to persuade undecided, potentially disenchanted voters to stamp the ballot in their favour.

The race for reach is on.

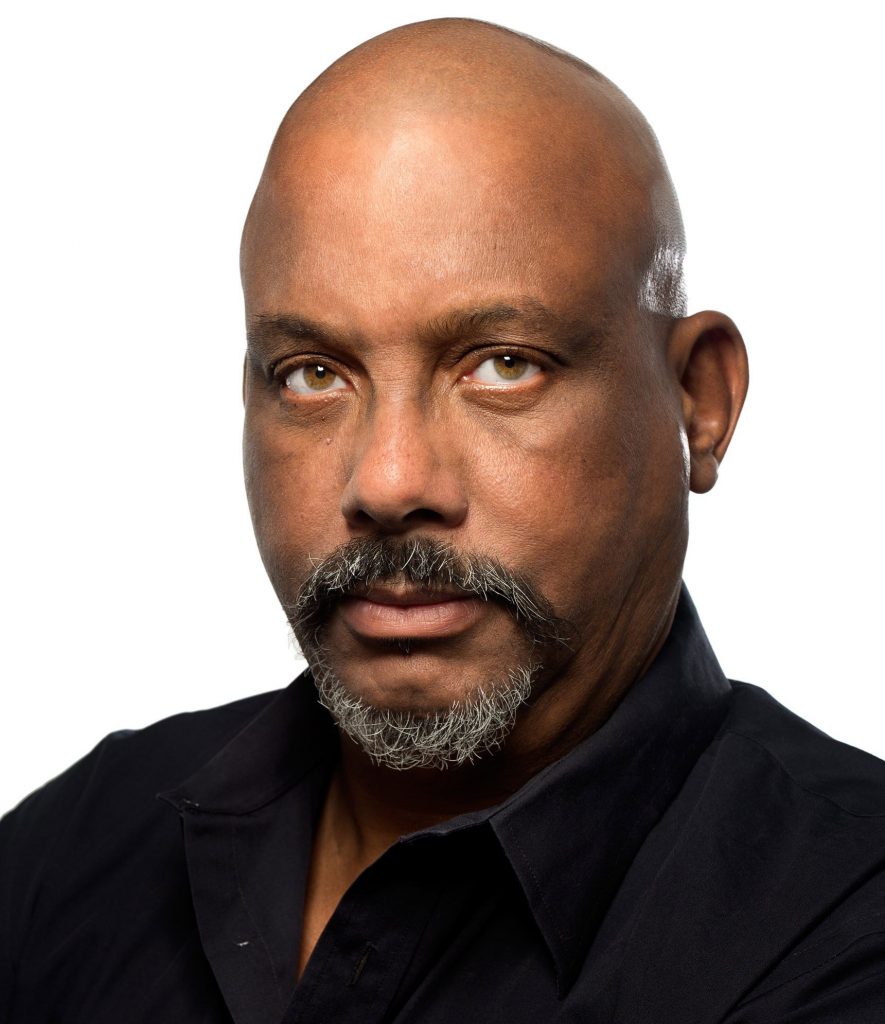

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there.

Comments

"Digital campaigning, 2020"