Fiscally responsible urban planning

Fiscal prudence (the goal of balancing a national budget) is an important goal for politicians and citizens who hold certain views on the economic policy spectrum. It is not a universal aim, as proponents of the increasingly popular Modern Monetary Theory believe it to be a somewhat moot endeavour. They contend that taxation is useful as a tool for dealing with socio-economic inequality, but is not the source of funds for government spending, when those governments print their own sovereign currency. It is, however, evident that prudence, or at least the illusion of it, is something that locals “educated” in the mainstream approach to finance believe in.

Even in the midst of a worldwide crisis, with record unemployment numbers in many countries, long lines at food banks in the great economic powerhouse up north, and locals in TT lining up for hampers from charitable organisations, the talk about the need to curtail the deficit is on the tongues and keystrokes of the chattering classes. All while they (we?) sit at home enjoying the luxury of virtual working arrangements, post selfies with fashionable face masks, and decide which Netflix shows to watch for the day; but I digress.

If we as a nation have made the policy decision that our ability to maintain a social safety net and other beneficial endeavours is tied to our ability to balance the national budget, then discovering ways to balance the budget is vital, even for those that disregard the idea of prudence.

Knowing the mindset of the chattering classes, it is a wonder that we as local urban planners have not used it to our advantage to sell the benefits of more sustainable approaches to development. Urban planning can assist in achieving fiscal prudence, among a remarkable host of socio-economic and environmental benefits. In this regard, the planning framework known as Smart Growth (SG) stands out as an innovative approach that can guide us towards better outcomes.

The US Environmental Protection Agency has defined SG as, “a range of development and conservation strategies that help protect our health and natural environment and make our communities more attractive, economically stronger, and more socially diverse.” More specifically, SG sets out ten principles for development:

1) Mix land uses

2) Take advantage of compact design (efficient use of land)

3) Create a range of housing opportunities and choices

4) Create walkable (pedestrian-friendly) neighbourhoods

5) Foster distinctive, attractive communities with a strong sense of place

6) Preserve open space, agricultural land, natural beauty, and sensitive environments

7) Direct development towards existing communities

8) Provide a variety of transportation choices

9) Make development decisions predictable, fair, and cost effective

10) Encourage community and stakeholder collaboration in development decisions

Taken all together, these principles lead to the creation of urban areas that look little like what we are currently developing locally, but probably look a lot like what we used to do pre-Independence, while the railways were still active and the car was not an everyday necessity.

We have our North American friends to thank for that post-Independence shift in approach to development; they exported it to just about every corner of the globe. However, we also have them and others to thank for helping us all understand the resultant consequences.

From a fiscal standpoint, the benefits of SG simply cannot be overstated. We have Hazel Borys and Kaid Benfield to thank for their collation of studies known as Code Score, which is an invaluable repository of information on the benefits of SG-like development. Here is a sampling of what they have uncovered:

Smart Growth America found that SG development generates 10 times more tax revenue per acre of land than conventional suburban development (the suburban sprawl that we continue to implement) and costs, on average, 10 per cent less on ongoing delivery of police, ambulance and fire services.

The City of London in Ontario estimates that sprawling development patterns (like ours) will cost them an extra $2.7 billion in capital expenditures plus $1.7 billion in operating expenses over the alternative (SG), or $4.4 billion extra over 50 years.

Joe Minicozzi, who studies the fiscal implications of land development patterns, has found that urban mixed-use, mid-rise (roughly three to 10-storey) buildings – that serve more functions and use land more efficiently – can produce as much as 25 to 59 times more tax revenue per acre than the suburban equivalent of separated uses and low-rise construction.

Then again, given that many preaching prudence live in oversized suburban homes – sometimes even in gated communities where they still want the State to pay to maintain their private roads – in areas where the public costs of maintaining the infrastructure and services exceeds the tax revenue generated from the wasteful spread-out setup, is fiscal prudence really our concern?

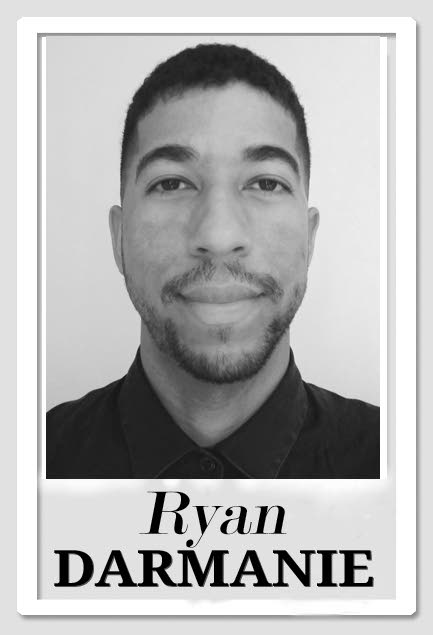

Ryan Darmanie is a professional urban planning and design consultant, and an avid observer of people, their habitat, and the resulting socio-economic and political dynamics. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or email him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"Fiscally responsible urban planning"