Language and history

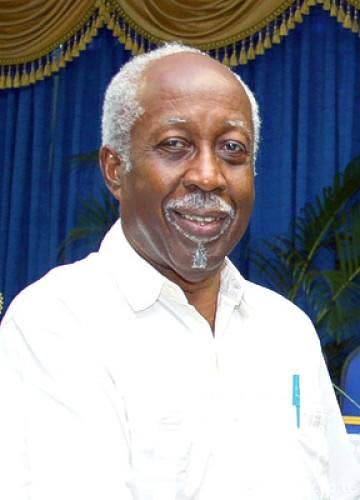

REGINALD DUMAS

A FEW DAYS ago, someone sent me a social media post, apparently written by Dr Lovell Francis, the Minister in the Ministry of Education. It reads: “Silly people are fussing because the Prime Minister used the word recalcitrant. Well I have some advice for you…It’s not too late to do a Barry…you can’t catch a plane like him but there are still pirogues around. Jump in, paddle out, keep paddling and give the rest of us a break from your dotishness. Thank you.” (The “Barry” reference is, I believe, to MP Barry Padarath.)

Actually, the Prime Minister hadn’t merely used the word “recalcitrant” when he spoke a day or two earlier. What he had said was “recalcitrant minority,” a phrase which has a specific resonance for many people of Indian origin in this country. Why? The following is what I wrote in my 2015 book The First Thirty Years.

“Attempting to explain his party’s electoral setback [in the March 1958 West Indies federal elections], Williams used a phrase that, more than half a century later, is still brandished by persons of Indian origin as clear proof of his – thus his party’s – racist convictions. That descriptive phrase, first used at a public meeting on 1 April 1958 and aimed at a certain group, was ‘the recalcitrant and hostile minority.’ It was taken by all and sundry to mean the population of Indian descent of Trinidad and Tobago.

“In his autobiography, Williams refutes the charge. He speaks of a circular letter addressed to ‘My dear Indian brother’ and signed ‘Yours truly, Indian.’ The letter, he says, ‘is seditious in intent, offensive, derogatory, an insult to the West Indian nation,’ especially as it refers to ‘our Indian people’ and ‘our Indian nation.’ And he goes on:

“The Indian nation is in India. It is a respectable, reputable nation, respected the world over. It is the India of socialism, the India of Afro-Asian unity, the India of the Bandung Conference…That is the Indian nation…,not the recalcitrant and hostile minority of the West Indian nation masquerading as ‘the Indian nation’ and prostituting the name of India for its selfish, reactionary, political ends.”

The explanation may have been persuasive to many. But the damage had been done among many others, and the phrase, which they considered unsavoury, has from one generation to the next clung like a malevolent limpet to his memory, and to the reputation of the party he founded.

Williams was later publicly criticised even by a member of his own 1958 Cabinet, Dr Winston Mahabir, minister of health and himself of Indian origin. In his 1978 book In And Out Of Politics, Mahabir wrote that Williams’ speech “contained generous ingredients of abuse of the Indian community which was deemed to be a ‘hostile and recalcitrant minority.’ [It] represented the greatest danger facing the country. It was an impediment to West Indian progress [and] had caused PNM to lose the federal elections.”

In both national and international affairs, you have constantly to watch your language. Perhaps because I spent so long in the Foreign Service, I try to be careful with mine, though I receive criticism both from those who are convinced that I am not deferential to authority (especially PNM authority, because, for such people, if you are black and middle-class – any class, really – you are duty-bound to support that party), and from those who feel that my language is too elliptical, not censorious enough. What to do.

Politicians often say things in public they and their parties come to regret. Remember Desmond Cartey? A heckler at a 1986 PNM political meeting kept shouting “Allyuh t’ief!” during Cartey’s presentation. Cartey lashed back: “All ah we t’ief!,” meaning that the whole country had been misbehaving itself. That response didn’t enhance his party’s electoral prospects.

Remember “Money is no problem?” Eric Williams had gone to Piarco in August 1976 to welcome back our first Olympic gold medallist, Hasely Crawford. The price of oil had again risen sharply, and Williams took the opportunity to say that the Cabinet would be discussing the issue of more funding for sport; money, he said, (was) “not a problem.” In other words, TT could now afford to spend more on sport. But you know what happened then.

I think Rowley spoke innocently, but innocence alone can ambush you. I agree with Amilcar Sanatan in his April 2 Global Voices article: “Language is not neutral. Political meanings are a part of language…(There is) a challenge to all public leaders to consciously use language that includes rather than excludes…(W)e cannot wash our hands of our history.”

We, the country. Contemptuous advice to “paddle out” is language that excludes, and does nothing for the country.

Comments

"Language and history"