A balcony visit a day keeps insanity away

What is the value of the in-between: the casual and under-appreciated forms of human interaction that lie somewhere in the middle of intimacy and isolation?

In those moments when we do not want to – or are not allowed to – be in close physical contact with others, yet do not want to be alone, what options do we have?

The current covid19, coronavirus, pandemic is testing societies worldwide in ways that have not been experienced, certainly in a long time. Psychologists have responded by sharing coping mechanisms on how to deal with the current norms of isolation and limited gatherings imposed by social distancing.

How do we preserve our sense of shared humanity? Phone and video calls, text messaging, and social media can and have been playing a role, but technology has yet to supplant that instinctive human longing for tangible social interaction.

The traditionally-designed cities of southern Europe, planned before automobiles and the pretense of privacy dominated every facet of city design, are once again teaching us a valuable lesson; are we paying attention?

In cities throughout Italy, musicians in isolation at home are playing their instruments and singing from their balconies; an entire neighbourhood was recorded singing along to a popular Rihanna song in unison from their windows and balconies. In Spain, a fitness instructor led a workout session from a rooftop with the surrounding apartment dwellers following along.

Of course, these stories that have warmed the hearts of the world, in two of the hardest hit countries in Europe, should come as no surprise to an avid urbanist. Traditional urban design has always facilitated these types of in-between interactions.

Streets are typically intimately scaled in these places, with buildings sitting at or near to the sidewalk, and the buildings replete with balconies and windows that look onto the public street. This provides the basic physical conditions that allow for people-watching from the comfort of your home. It represents the casual surveillance of street and neighbourhood life that is so vital to community building and a sense of belonging.

Here, distance and orientation play a key role. Spaced too far from the sidewalk and the buildings on the opposite side of the street, and this entire system of in-between interactions that is allowing for this strong sense of community in Italy and Spain disappears. The distances will be too great to perceive the face of a neighbour on their balcony, the fitness instructor’s movements, or the activities of a pedestrian walking on the adjacent sidewalk; or to appreciate the sound of the human voice singing or the musician playing the guitar.

Distance regulates our five senses. The greater the distance, the lesser our ability to surveil our environment and interact with others. The importance of distance, the value of a human-scaled street and community, and the role of the humble balcony have, in a time of uncertainty and anxiety, come to mesmerize a world that is increasingly forgetting the meaning of these things. Countless news articles are being written about the trending videos showing the sense of community in Italian and Spanish cities.

In our unfortunate American-driven obsession with the pretense of privacy and individualism, we have created vast swaths of single-family homes set in isolation from neighbours. Alternatively, and now increasingly, we are building entire apartment developments that lack streets and sidewalks, and instead comprise of a roughly strewn together arrangement of buildings, parking lots, grass, and driveways, with little to no semblance of the physical conditions for community life built it.

The buildings within these “modern” apartment compounds are typically spaced far apart and/or intentionally oriented in anti-social ways that could never replicate the community-building layout of a traditional Italian or Spanish neighbourhood built for social interaction.

Similarly, the apartment buildings being built in our existing cities are designed to keep residents physically and visually “quarantined” from the horrors of the city and its streets; the designers of these will tell you just as much as they try to justify their neighbourhood-destroying creations.

The term resilience refers to the capacity to recover quickly from disasters, hazards, and other challenges. A huge component of resilience though, is the ability of the collective human spirit to endure.

So, for those urban professionals – the architects, planners, and others – throwing around the term resilience as the new, in-vogue buzzword, yet actively designing out opportunities for social contact and community-building by the very way that they lay out entire developments and design individual buildings, take note. You are killing the capacity of the human spirit to survive in times of turmoil, but also to thrive in times of normalcy.

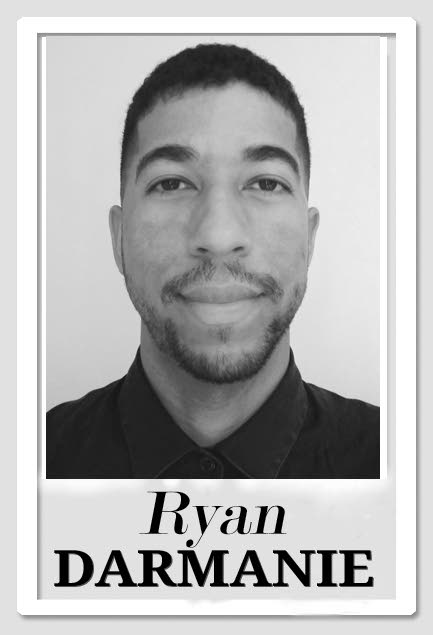

Ryan Darmanie is a professional urban planning and design consultant, and an avid observer of people, their habitat, and the resulting socio-economic and political dynamics. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or email him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"A balcony visit a day keeps insanity away"