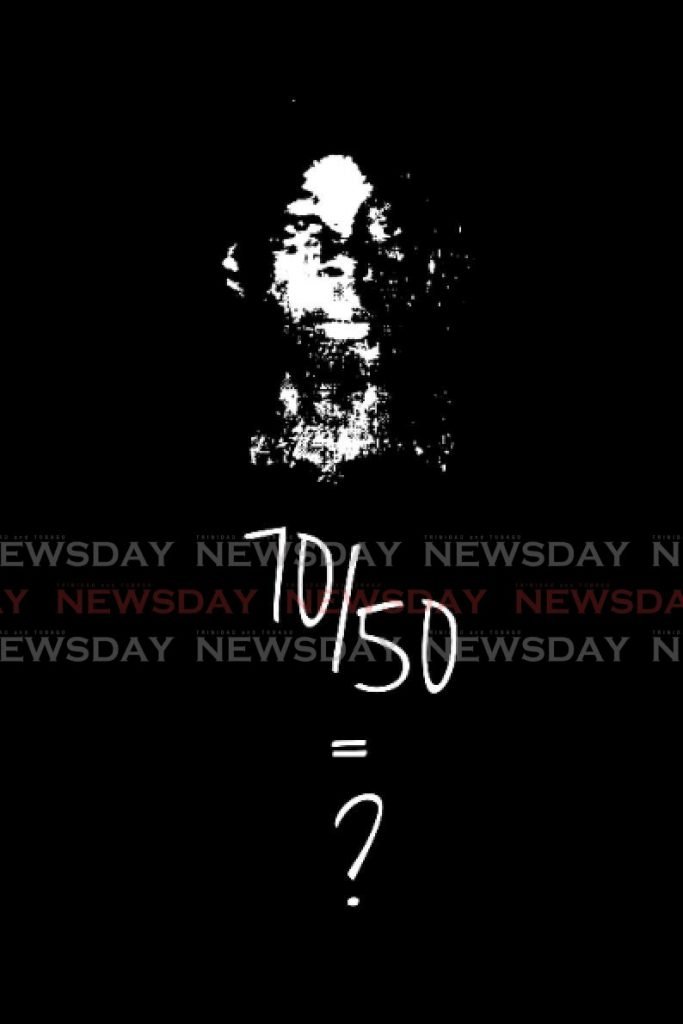

70/50 mas band reflects on 1970 Black Power Revolution

THIS year marks 50 years since the dramatic events of 1970.

Those events, sometimes referred to collectively as the Black Power Revolution, involved the confluence of a series of activities: artistic activism, protests over racial discrimination against Caribbean students at a Canadian university, Cabinet resignations, a state of emergency, a failed Defence Force mutiny, the exercise (legitimate and illegitimate) of police power, damage to property, and fears of violence among all camps.

Though these things happened over 50 years ago (and indeed some predated 1970, some spilled over into subsequent years) they remain raw in the minds of many.

As with most highly-divisive historical moments, many look upon 1970 as a kind of victory, others a pyrrhic one: a dangerous moment when the tinderbox of race threatened to inflame the issue of basic rights and take TT into disorder.

Into this maelstrom comes 70/50, the latest Carnival band from fashion designer Robert Young, which aims to look back, reflect and pay tribute to the complex legacy of 1970.

Young, 55, who wears large glasses with transparent frames and sports a heavy salt-and-pepper beard, is well known for The Cloth, the fashion label he founded in 1986. His designs, which frequently involve collages of form, palette and texture, often contain elements of protest. Think stained-glass window meets placard.

For him, the theme of this year’s band is personal. His father, Joe Young, was a masquerader in the band The Truth About Africa, which was brought out in 1970 and was, for some, the start of the year’s frenetic series of events.

Joe Young was a founding member of the Transport and Industrial Workers' Union (TIWU) and frontline member of the United Labour Front (ULF), who later sat in the Industrial Court.

In that band he wore chains as a comment on the provisions of the Industrial Stabilisation Act, legislation which did not sit well with the labour movement, which largely felt not enough was being done to bring about true race parity in the wake of independence, and that freedoms were being suppressed.

“I was five years old at the time,” his son recalls. “My relationship with him was coloured by the fact that sometimes he just could not be around. He was there but not there. Significantly present but also significantly absent.

“When he died in 2012, someone said my father could not have done what he did for workers if he was at home all the time being a family man.”

A son’s yearning to bridge the gap between him and his father might be one motive behind the decision to bring out a small band inspired by 1970.

But in the process, Robert Young has, through his Vulgar Fraction collective over the years, made a habit of producing mas that goes against the grain.

“Vulgar Fraction is a way for art and mas to be accessible as a living thing,” he says of the band. “It is allowing people to access the making of mas. The mas doesn’t end up looking like it was expensive – but that’s a statement too, about how we consume Carnival, and the status we get from playing certain kinds of mas.”

The band first came out in 1997. It normally attracts a small but dedicated following comprising an array of artists, activists, academics and tourists. Masqueraders are encouraged to devise their own costumes.

Last year’s theme was Nothing, a fusion of Yoruba references with sailor mas; the year prior was Playing White, which in its own way intersected with this year’s 70/50 theme.

In relation to 70/50, Young is still working out the final details of how the band will communicate its ideas about 1970. At the moment, he’s drawn to the idea of using symbols, graphics, images of protesters, silhouettes, portraits of specific figures, and imagery surrounding Ethophia.

The bandleaders intend these items to relate to figures such as Basil Davis, a protestor killed by police on April 6, 1970. It was reported Davis had tried to intervene in the arrest of another person.

Whatever the context, the shooting of a protester troubled many and came days before the resignation of ANR Robinson, Tobago East MP, from the Cabinet of prime minister Dr Eric Williams.

Both events arguably added momentum to the looming idea of a general strike. Williams declared a state of emergency on April 21, 1970, and Black Power figures were arrested. There were riots and four people died.

At the same time, a group of rebel soldiers, led by Raffique Shah and Rex Lassalle, mutinied and took hostages at the army barracks at Teteron.

According to the University of Central Arkansas, six US naval ships (and 2,000 troops) and two British ships were deployed offshore on April 22, 1970. The US government airlifted military assistance (weapons and ammunition) in support of the government on April 23. Troops suppressed the mutiny on April 25.

The international flavour of the events is not surprising given that one early incident which had provoked protest was outrage over the treatment of Caribbean students who had protested racism at a Canadian university.

There was a sequel to 1970. Between 1973 and 1974, figures from the National Union of Freedom Fighters (NUFF) – variously described as “an armed revolutionary group and a “guerrilla group,” set up in 1971 in opposition to the government – were captured in a camp in the Northern Range. Some 18 people, including 15 rebels and three policemen, were killed. Among those reportedly killed was 17-year-old Beverly Jones, another figure of interest for the bandleaders of 70/50.

-

For Young, these events raise questions.

“Access to power still does not reside in the hands of people like Beverly Jones and Basil Davis. They have been erased. Did they dream of the society we have now?”

Young also links questions about power, race and capitalism to the fate of the planet. He is keen to make 70/50 environmentally conscious, asking masqueraders to use only recycled materials in their contributions to the costumes.

“We are using old, used shirts. The idea we’d like to convey is of a shrine where these shirts are used to venerate ancestors.”

The names of some 1970 protesters will be on the clothes, as will symbols like the “equals” sign and the question mark, reflecting ambiguities surrounding the achievements of 1970.

Young also wants the band to encourage activism more generally, particularly in relation to climate change.

“What if we take the energy of the 70s and use it to think about climate change?” he says. “There’s a type of grief we haven’t processed on 1970, and grief for our climate crisis. It’s a holy call, because the environmental D-Day is supposed to be coming in 2030.”

The band will be launch at its base, which it shares with The Cloth, at 24 Erthig Road, Belmont, on February 11 at 6 pm.

At one point, Young wanted to join the priesthood: to be a man of the cloth – hence his label’s name. His zealous dedication to fashion has taken his work to stages all over the world, in collaborations with iconic figures like Peter Minshall, David Rudder, Andre Tanker, 3canal. Throughout, there’s a spirit of punk – of revolution.

But Young is not entirely sure his father, the trade union activist, would have approved.

“He might say. ‘What are you doing? Revolution does not happen like this. It happens when there’s a real ferment, an energy, a movement.

“‘And that’s not happening these days.’”

Comments

"70/50 mas band reflects on 1970 Black Power Revolution"