Treat crime as a disease

kmmpub@gmail.com

We must sweep aside our sheet of tears and rage and embrace cold, impersonal data. A public health approach will win the battle against crime.

Seemingly random sprays of bullets at maxi taxis. Mass shootings with military grade weapons. Two doctors dragged off, one dead. Another young doctor stabbed in his practice.

No wonder the red mist has clouded our eyes.

It is tough not to be emotional about crime. We understandably need to lash out at the people that have hurt us and those closest to us. The result: we call for policies that have not worked: executions, longer sentences or states of emergency.

The attack on our doctors has brought it home (if it wasn’t already) that violence is not confined to inter-gang warfare. No institution is sacred – not a church and not a hospital.

But what if the key to tackling crime lies in reaction of those same institutions? There was outrage when the doctors’ attackers were treated on the same ward by their colleagues, but this hides a clue to the solution: use data to treat crime as a public health problem.

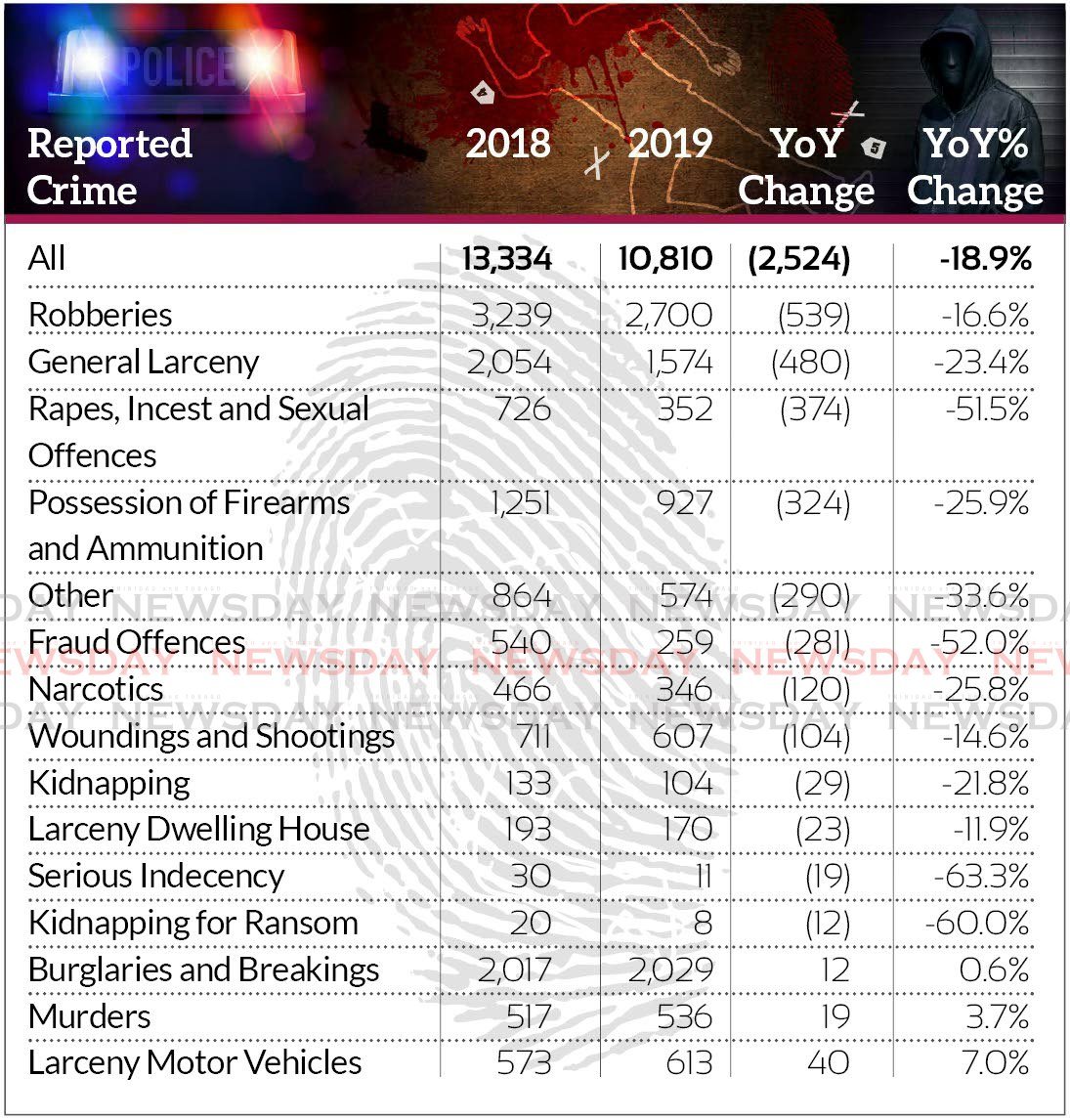

What does our data show? Firstly: overall reported crime has fallen by 18.9 per cent from to 10,810 in 2019, across all major categories. Robberies in particular fell from 3,239 in 2018 to 2,700 in 2019.

Now you might ask whether that police service data is reliable. Crime is likely to be underreported. But is it that likely that crime was less likely to be reported in 2019 as compared to 2018? And if the police wanted to fudge the numbers you would think that murders would be the first one. It seems reasonable to take the numbers at face value.

Overall crime is falling. We must first acknowledge this and stand against the prevailing rhetoric. If we don’t, we risk abandoning policies that have proved to work.

Once we’ve done that: we can focus on our biggest problem: violence. Murders are up by 3.7 per cent and those crimes that do happen have become more violent. Men remain a problem: the Inter-American Development Bank reports that up to 30 per cent of women experience domestic violence.

So what does a public health approach mean? It means that the police alone cannot prevent all crime. Society and the whole government must take responsibility to use data to tackle crime, what the Police Commissioner has called an “intelligence driven” approach.

Britain’s Home Secretary has seized on this approach: announcing last year that: “Violent crime is a disease…I’m confident that a public health approach and a new legal requirement that make[s] public agencies work together will create real, lasting long-term change.”

According to the UK’s Home Office: “The new ‘public health duty’ will cover the police, local councils, local health bodies such as NHS (National Health Service) Trusts, education representatives and youth offending services. It will ensure that relevant services work together to share data, intelligence and knowledge to understand and address the root causes of serious violence including knife crime. It will also allow them to target their interventions to prevent and stop violence altogether.”

Practically, a public health approach leads to targeted policies. The University of Chicago’s Crime Lab has found that the introduction of lights in New York streets “led, at a minimum, to a 36 per cent reduction in nighttime outdoor index crimes.” Data like this changes the cost-benefit analysis for many ministries’ projects, even if they don’t seem directly related to crime.

Take released prisoners: TT's reoffending rate is between 53-74 per cent. At last official count (back in 2010), more than 2,608 prisoners are released each year. Do the maths: that amounts to about 1,400 people who are just about guaranteed to commit a crime.

How can stop this quickly? In Liberia, the American Economic Association “recruited criminally engaged men and randomised one-half to eight weeks of cognitive behavioural therapy designed to foster self-regulation, patience, and a non-criminal identity and lifestyle. We also randomised $200 grants…When cash followed therapy, crime and violence decreased dramatically for at least a year.” Simple and effective.

Similarly, researchers at Justice Tech Lab have found that the expansion of DNA registration in Denmark reduced reoffending by 43 per cent in the following year.

These are huge and direct effects. If we are serious about tackling violence we must reverse the rhetoric of pain. Advocating policies based on emotion will simply “cut off our nose to spite our face.” It is time we start treating crime as the disease it is.

Kiran Mathur Mohammed is a social entrepreneur, economist and businessman. He is a former banker, and a graduate of the University of Edinburgh.

Comments

"Treat crime as a disease"