Some planners are more equal than others

Act No 1 of 2019 – an act to amend the Planning and Facilitation of Development Act, 2014 – was assented to on January 25.

One of the purposes of this amendment was to refine the qualifications for the position of director of planning of the to-be-established National Planning Authority.

Now, stated in the act are two acceptable educational qualifications for the position: “an undergraduate degree in the field of urban and regional planning and a postgraduate qualification in urban and regional planning or a related field” or “an undergraduate degree in a social, environmental or design science and a postgraduate degree in urban and regional planning.”

The second option, and assumedly its precise wording, was added – on the recommendation of local planners – because many, if not most, planners possess undergraduate degrees in fields other than urban planning. The decision to specifically narrow what those undergraduate degrees should be is, however, quite baffling.

The companion legislation, the Urban and Regional Planning Profession Bill, 2019, was recently debated in the lower House of Parliament. It states that those seeking to be licensed urban planners must have an undergraduate or post-graduate degree in urban and regional planning.

A planner who may be deemed qualified and competent enough to be licensed; who may have decades of experience; who may have a masters or doctorate in the field; and who may be highly regarded in the profession, may not be eligible to be the director of planning in this country, on the basis of his/her undergraduate degree.

The degree you gained when you were probably not yet a fully formed adult determines your eligibility to hold the highest urban planning position in the nation. With the wrong undergraduate degree, it matters not how much you have perfected your craft.

Someone with lower-ranked qualifications, like a bachelor’s degree in planning and a post-graduate diploma in planning or some related field, can be deemed more qualified than someone with a master’s or doctorate degree in planning.

Someone with lower-ranked qualifications, like a bachelor’s degree in planning and a post-graduate diploma in planning or some related field, can be deemed more qualified than someone with a master’s or doctorate degree in planning.

Urban planning is, at its core, a generalist field of study that deals with very complex, nuanced, and interconnected issues. It is a field that no doubt benefits from having people from the widest array of backgrounds and perspectives.

The UCL Barlett School, ranked in 2019 as the best institution in the world by QS in the field of architecture and the built environment, requires “an upper second-class bachelor’s degree (in any field) from a UK university or an overseas qualification of an equivalent standard” for admission consideration to its city planning master’s programme.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the second-ranked university in that survey, will similarly consider the application of a candidate with an accredited bachelor’s degree in any field of study for its city planning master’s programme.

The top graduate from one of these programmes could go on to do ground-breaking work in the field of urban planning, yet if his/her first degree was not in a social, environmental, or design science, he/she should not waste time applying to be the director of planning. The story is the same for most educational institutions, including my own, which happily accepted me with a bachelor’s in computer science.

This poorly worded amendment – based on bad advice – reminds me why I have yet to cancel the job alerts that flood my email inbox daily. Over the years, I have read hundreds of job descriptions for urban planning positions in the US, Canada, Australia, and the UK from entry level to director.

What I have come across, is unlike what has been written into our legislation. Almost universally, the requirements are preferably a master’s in urban planning, or if not, a bachelor’s (with additional years of experience required).

A candidate’s undergraduate degree is understood to be sufficient, as it satisfied admission into and matriculation from the educational institution that granted the master’s. End of story. Furthermore, an undergraduate degree only tells you the major area of focus of someone’s studies.

Even though I majored in computer science as an undergraduate, I took two architecture courses, an economics course, two courses in introductory and advanced geographic information systems, and two urban planning courses, in preparation for postgraduate study.

In other words, potentially a far wider breath of planning-related knowledge than someone who majored in environmental science, and took few courses outside of their core area of study.

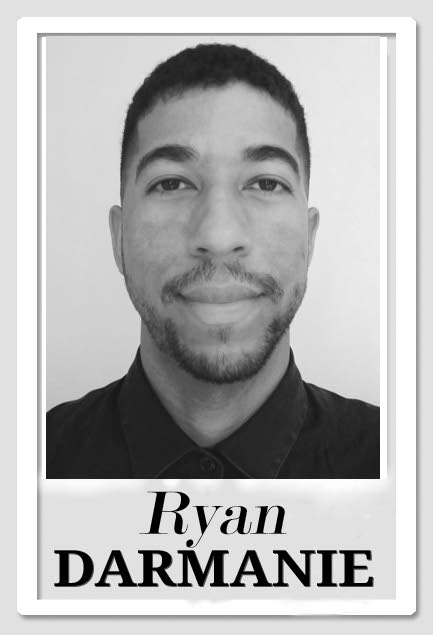

Sorry Ryan, you are still a second-class planner.

Perhaps the qualified first-class planners should be writing this column instead. They would decidedly be far more adept.

Sorry Ryan, you are still a second-class planner.

Perhaps the qualified first-class planners should be writing this column instead. They would decidedly be far more adept.

Comments

"Some planners are more equal than others"