This dragon can dance

MOST learn to walk once, but Earl Lovelace learned to walk twice.

The first time was as a small child in Toco. The second was when, at about five or six, he fell seriously ill, was hospitalised, and believed he was about to die.

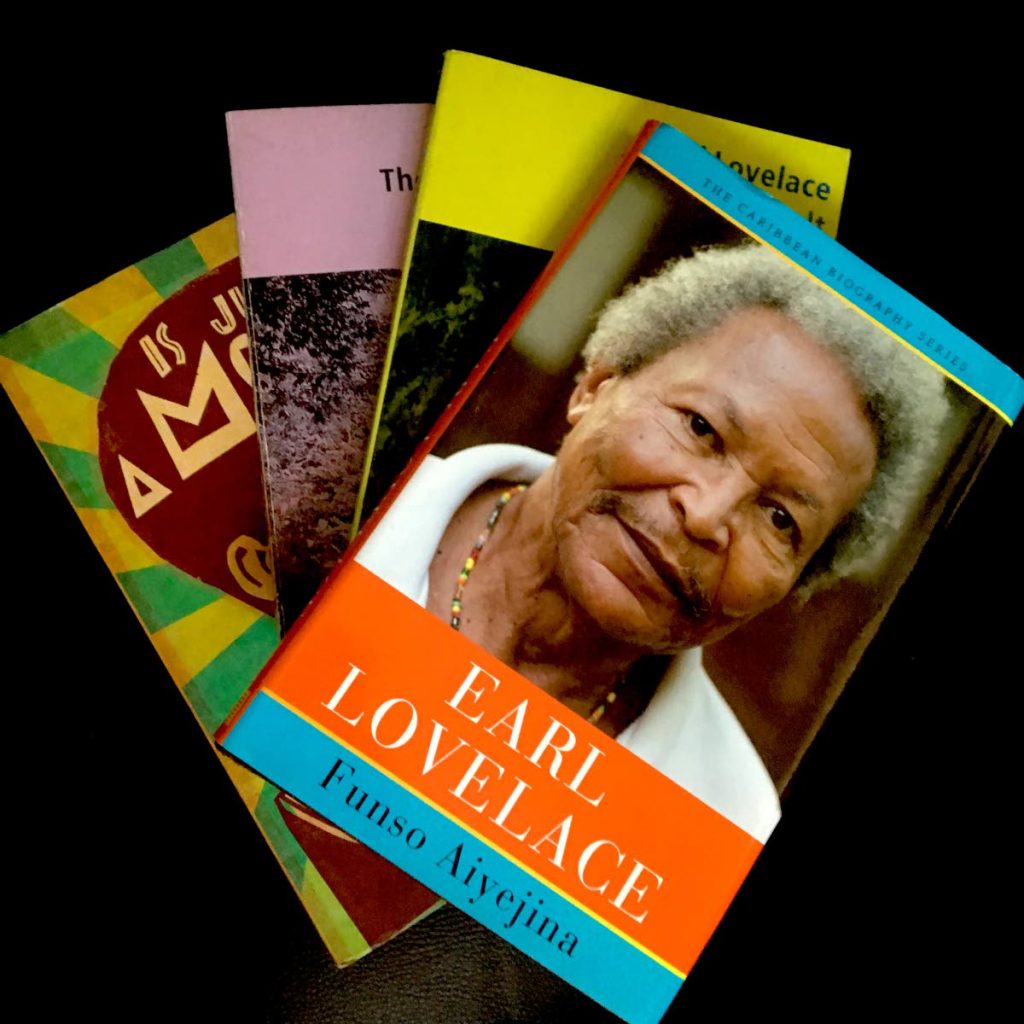

Destiny had other plans, as made clear by Funso Aiyejina’s biography, Earl Lovelace, published in 2017 by the University of the West Indies Press as part of its Caribbean Biography series.

“He recovered from the typhoid and had to learn to walk all over again,” Aiyejina informs readers.

It’s a useful book to turn to in the year in which Lovelace’s novel The Dragon Can’t Dance turns 50 – an anniversary celebrated by a series of events at May’s NGC Bocas Lit Fest.

Aiyejina is a friend and fan of Lovelace (the novelist dedicated his 2011 novel Is Just A Movie to him). The overlap is fertile. The biographer gives insight not otherwise available. He draws equally from public sources and private conversations and personal material. The result is a pleasingly broad examination of Lovelace’s worldview.

For example, we chip effortlessly from walking to dancing. Dancing, Lovelace says, “is perhaps the most affirmative human expression of self, indicating as it does the exercise by the individual of power/control over his own body.”

Further, “if you look at African dances you will see that they show the body in control of itself. The dancer is not seeking to traverse space, like the waltz and other European dances, but concentrates on mastering his/her body within a limited space. The body becomes the universe.”

But a good biography does more than lift the veil on the thinking of its subject. It tells us why that subject is worthy of attention. And it tells us something new.

Though running for a brief 114 pages, this book succeeds on all counts.

We discover Lovelace has worked on an autobiography, fascinating excerpts of which are sprinkled through the narrative. We read of the writer’s formative experiences growing up. We hear of a heartbreaking dilemma he faced as a child, when he was made to choose between an aunt and his biological mother.

“Now as I think of it, I see how devastating it must have been for Aunt Lorna,” Lovelace says. “How much of a traitor I must have seemed. I loved Aunt Lorna dearly and I loved my mother. I chose to go to live with my mother. It hurt Lorna…I had been required to choose in a situation in which any choice was the wrong choice.”

These disclosures are moving, but they also raise important questions about the shape of Lovelace’s work. It’s intriguing to consider whether the experience with Aunt Lorna coloured the writer’s estrangement with the idea of a motherland, whether colonial or otherwise.

Aiyejina pays a lot of attention to a publication called the Frog Hopper, described as “the annual magazine of the Eastern Caribbean Farm Institute,” a publication which served as the platform for Lovelace’s first outings as a writer. While this material is important, the Frog Hopper section sometimes feels belaboured in a book that does not require its argumentation.

In contrast, there is relatively less critical discussion of Lovelace’s novels. Which is well and good. The UWI Press’s Caribbean Biography series, which has also published concise biographies of Beryl McBurnie, Marcus Garvey and Derek Walcott, is becoming known for its slim, elegant volumes and Aiyejina may not have felt it appropriate to take up space with detailed academic critique. A single novel by Lovelace could probably inspire several books.

Elsewhere, Aiyejina writes with humour and in quietly stylistic prose that is admirable for its handling of complex ideas with clarity and verve. All of it is finely modulated. We never lose sight of the writer behind the books.

So in an era when the trauma of the Secondary Entrance Assessment examination is still upon us, we are informed of the great writer’s own childhood experiences with exams as well as his misfortune of having terrible teachers who embodied the worst aspects of colonial education.

We also learn of Lovelace’s start as a poet before becoming a novelist, a matter which strikes me as an important observation because it explains why so much of his prose has the feeling and tone of poetry.

Aiyejina also manages his knowledge of Lovelace’s output expertly, drawing connections between aspects of the writer’s life and the fiction. It all adds up to a short but meaty book that is not afraid to enter the gayelle with its dancing subject. Compulsory reading for anyone interested in Caribbean ideas and writing.

Comments

"This dragon can dance"