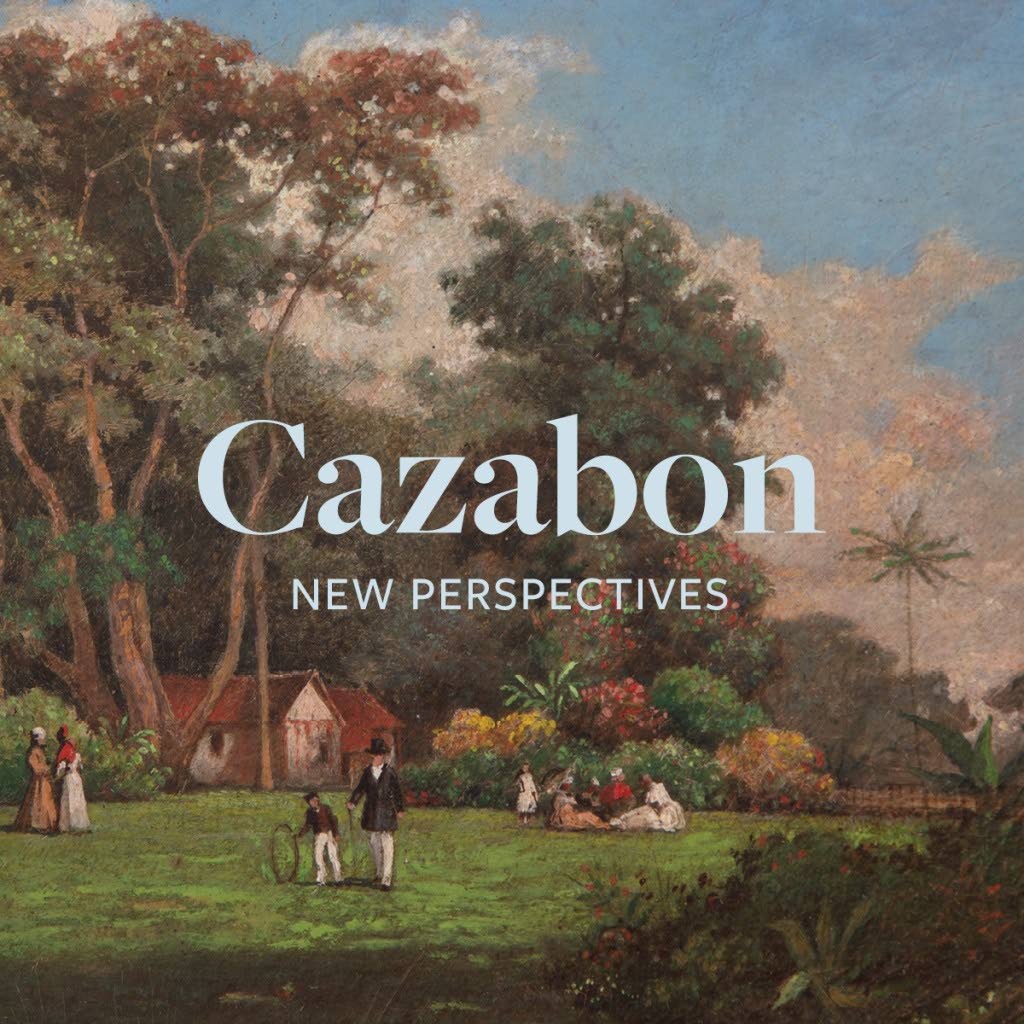

New perspectives on Cazabon

Let’s face it. When people start to criticise and analyse art, the academic language and jargon can make things a bit dull.

Fortunately, this is not the case with the book, Cazabon: New Perspectives with contributions by local artists Kenwyn Crichlow and Donald “Jackie” Hinkson, art dealer Mark Pereira, and writer and Newsday Editor-in-Chief Judy Raymond.

The narrative style of writing presents an analysis of the works of 19th century Trinidadian artist Michel Jean Cazabon, insights into the man and his career, as well as the practices, politics, and society of TT at the time through his work and in the context of other artists of that time.

Although the reader may need a dictionary at times, Cazabon: New Perspectives is a surprisingly easy read. It gives an appreciation of the visual appeal of Cazabon’s work and techniques from an academic standpoint, going into depths probably not considered by the average viewer, in a palatable form. The use of the many pictures of his works also helped.

The main message I got from the book was that his work, including portraits and landscapes, should not be taken at face value.

For example, Crichlow examined how artists who studied in England worked and were trained at the time. He noted that landscapes were linked to empire-building in the Caribbean, and presented how well European society had reproduced itself in the region. He even described the techniques used to manipulate how and to what the viewer paid attention.

“The artworks functioned as recordings of events, advertisements of commercial possibilities, and marine and scientific studies. Their production, substantially different in nature, form and quality from the art of the Parisian salons, was instrumental in the visual projection of imperial power in the region and in Europe.”

He said Cazabon was obviously familiar with the techniques and used them but kept his work separate from the politics of the day. Crichlow said Cazabon felt his work should be an “accurate reflection of observation and a consistent narration of the actual experience of a place” although he sometimes romanticised scenes.

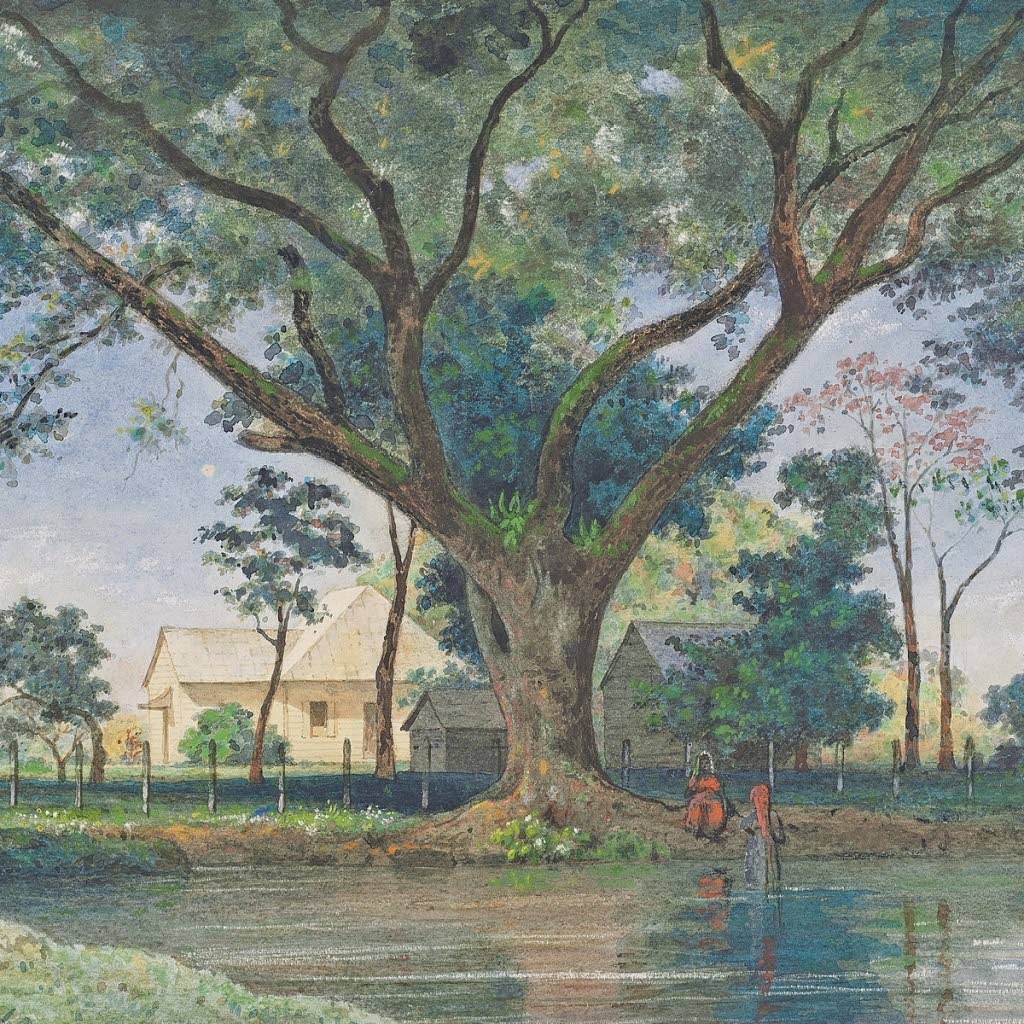

In Hinkson’s contribution, he examined the light depicted in the paintings and Cazabon’s use of human figures.

Cazabon worked in various parts of the world including North Africa, South America, Europe, TT, and other West Indian islands. Hinkson said there was a difference between the light in the tropics and that in the colder countries of Europe. Yet comparing paintings from different countries and climates, some had similar light.

The topic brought on a memory from a Hollywood movie about an architect where one character spoke about light. He said, “The light in Barcelona is quite different from the light in Tokyo. And, the light in Tokyo is different from that in Prague. A truly great structure, one that is meant to stand the tests of time never disregards its environment. A serious architect takes that into account. He knows that if he wants presence, he must consult with nature. He must be captivated by the light. Always the light. Always.”

The same must be true for any visual artist.

Hinkson said the discrepancies could be due to deterioration of the paintings over the years, or deliberate or unconscious superimposition of the light when Cazabon later completed his works in his studio.

Regarding the use of figures he said, “Cazabon used it widely and often wisely and cleverly, sometimes to introduce a focal point of interest and relief and sometimes simultaneously to hint at an admiration for those performing ordinary but essential tasks...

“At other times Cazabon seems to be venturing closer to stronger social commentary or observation which may appear to be in contradiction to the dominant mood of contentment in his serene, bucolic landscapes.”

Hinkson said the lack of detail in some works, the explicit detail in others, the depictions of lower classes in society, and other issues raised many questions about Cazabon’s circumstances, patronage, opinions about society and his own work, and other aspects of the artist’s life.

Raymond raised even more questions about Cazabon’s work. While acknowledging the artist’s skill, she highlighted the inconsistencies with real life. She also questioned how he may have viewed non-whites given Cazabon’s family history and the social structure of TT just after the abolition of slavery.

She said Cazabon held a special place in the hearts of Trinidadians because people think of him as “one of us” – a Trinidadian of mixed race. She said his work brought on a sense of pride and nostalgia because people know and recognise the scenes depicted. However, she said nostalgia was more about wishful thinking.

“The nostalgia evoked by Cazabon is for a Trinidad that may never have existed. And the more you look at his paintings, the odder they start to seem. One reason for that is because we look at him as if he were unique. In fact, Cazabon fits firmly into a tradition, and once he is set into this context, his paintings become, if no less idiosyncratic, then at least more understandable...

“Cazabon wasn’t painting his pictures for himself, and he wasn’t starting from scratch. He was trained and worked in a European tradition that he continued to follow faithfully in many respects. Some of the truths of West Indian life couldn’t be fitted into artistic moulds made in Europe, and that’s why they don’t appear in Cazabon’s work. What exactly did Cazabon leave out?”

One of those things left out was the majority of the island. She noted that with a few exceptions, he mostly painted scenes in Port of Spain and environs, and in south Trinidad near where he was born. Also left out were the First Peoples who were “barely considered human,” as well as the effects of slavery and the problems after its abolition.

Raymond compared Cazabon’s drawing with writings from the 19th century which described the “wretched conditions” and ragged appearance of Indian indentured workers. They do not coincide with the healthy, well-dressed Indians in his work.

Lastly, Pereira contributed biographical notes of Cazabon’s contemporaries, as well as a visual comparison of the artists’ paintings of the same scenes. “Until now, Cazabon’s contribution to nineteenth-century art in Trinidad has been examined in isolation, and at the expense of these other artists working in the same landscape at the same time. Viewing the works of these other artists may also offer not only further insights into life on the island but also useful points of comparison with Cazabon.”

* Cazabon: New Perspectives will be available in a limited hard-cover edition at 101 Art Gallery, Newtown, and in soft-cover at Paper Based Bookshop at Hotel Normandie, St Ann’s, and all branches of Nigel R Khan Booksellers from October 5. A book launch also takes place on this day, 5 pm, at the art gallery.

Comments

"New perspectives on Cazabon"