The underlying cause of unauthorised development

The pervasiveness of unauthorised or informal development has been used as an excuse for why our urban planning regulations are unimportant. I’ve been told that overhauling regulations, in order to effect change in the functionality of our built environment, is moot since people don’t comply. There is a built-in assumption that people are inherently law-breakers.

That may be true for a select few, but unlikely for the many. It’s an excuse, as far as I can tell, for not opening our minds to the confluence of socio-economic factors that explain why so many urban planning efforts have failed over the years.

While we may be unable to fully eradicate unauthorised development, I have no doubt that it can be decreased substantially.

Conventional planning practice has taught its adherents that places can be planned and designed while dismissing basic human motivations, including innate behavioural patterns and inescapable economic forces.

Our urban planning approach – which involves the modernist, American-conceived idea of separating different categories of land uses; using land inefficiently; privatising amenities and therefore human interactions; and creating a dependency on costly imported private cars – is at odds with our sociable, collectivist nature, the very organic intermingling of residential and commercial activity that makes functional cities, our peculiar physical reality as small islands, and the economic realities of average housing income.

The most influential planner of the last century once said, “Any city that’s tearing down its buildings just to make money for a development, or just to have novelty, is doing something criminal.”

Isn’t it also criminal to ignore the well-documented consequences of planning regulations, just to create a built environment that fulfils some anti-urban, anti-city bucolic fetish?

But I’m just a lone inconsequential voice with one master’s degree in urban planning, questioning the established players with their decades of experience, or multiple degrees – MBAs, PhDs, PMPs and every other imaginable letter after their name.

Luckily, far more established and credible planners than myself are there to justify my sentiment.

Shlomo Angel, New York University professor, researcher, and well-known author of Housing Policy Matters, singles out unrealistic planning regulations as one of two reasons for the high cost of housing, particularly in developing nations.

Alain Bertaud, former principal urban planner for the World Bank, with years of multi-continental working experience states most clearly that:

“When a large part of the urban population cannot afford the cost of the minimum standards imposed by regulations, the enforcement of the planning rules becomes impossible…in many cities of developing and emerging economies, informal (squatting) settlements typically represent 20-60 per cent of the total housing stock”.

Even in places with strong regulatory enforcement capabilities, informal development will still manifest, albeit in a different way.

With weak enforcement it will show up as illegal land subdivision in agricultural areas, hillsides, and other unintended places, while it will show up in the developed world as illegal building subdivision and extensions of existing homes. In 2008 it was estimated that 114,000 illegal new dwellings were built in New York City between 1990 and 2000.

Further compounding our predicament is the lack of transparency in urban planning regulations. As a layperson, one can, as one could have nine years ago when I entered planning school, locate online a copy of the zoning code for thousands of municipalities in the US – even for Native American settlements!

So, we try to enforce planning regulations that are incompatible with our very culture and blind to the physical reality of land space and the economic realities of households, and don’t publish these regulations for public knowledge.

Yet we’re scratching our heads in bewilderment, and, one would assume, digging into the depths of our teachings from multiple academic qualifications to figure out why our planning is not working. As the rapper of TT descent, Cardi B, would remark: “Okurrr?”

Of course, the disciplinarian decision-makers among us can’t see this. They are like hammers, to whom everything looks like a nail in need of a forceful pounding.

Luckily, good sense and critical thinking still exists, as evidenced by encouraging recent interactions with important actors in the housing and tourism sectors, who have been reading this column, and have been able to internalise how urban planning affects their own work.

All hope is not lost, and with a bit of luck, I won’t end up, in the long run, as the Bernie Sanders of the local planning profession, with the gatekeepers unfairly deriding me as a gray-haired, curmudgeonly old man harping on the same points unendingly. But then again, if things don’t change or get worse, that comparison is flattering, in a way that may not be immediately perceptible.

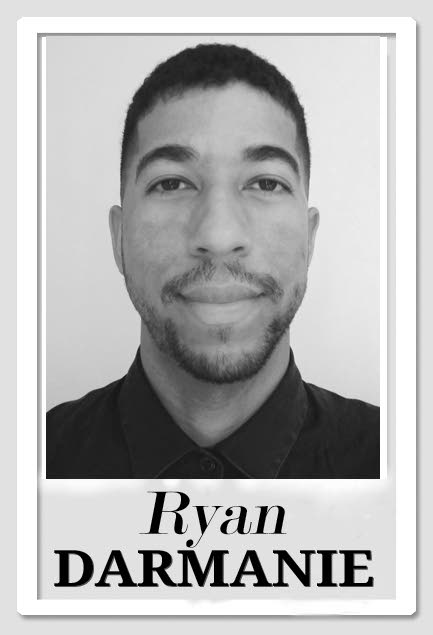

Ryan Darmanie is an urban planning and design consultant with a master’s degree in city and regional planning from Rutgers University, New Jersey, and a keen interest in urban revitalisation. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or email him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"The underlying cause of unauthorised development"