Are we learning lessons?

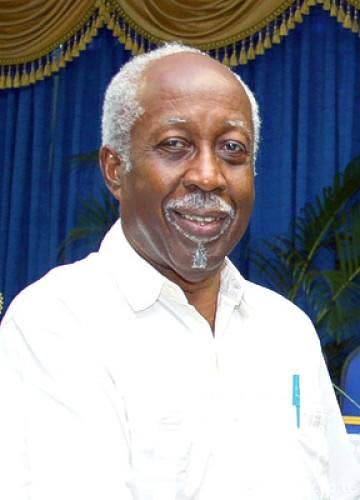

REGINALD DUMAS

ON THE Marlene McDonald matter, we’ve been running the risk – actually, in TT today it’s not so much running the risk as following the mindless tradition – of concentrating on personalities instead of principles, on political snarling, and on losing sight of the wood for the trees.

As a citizen, I’ve been embarrassed by the McDonald affair. But I cannot spend my time in a fog of embarrassment. For me, what is important is that, as a country, we learn lessons (if we haven’t already) from the events of the last few weeks, and find and apply best practice solutions. What are some of the lessons?

First, the role and functioning of the Integrity Commission. To put it mildly, this body has lived a chequered life. There have been public disputes between its members; resignations by its chairmen; clandestine investigations of individuals, provoking strong suspicions of political interference and manipulation; a successful lawsuit against it by the current Prime Minister.

“Integrity” hasn’t always seemed the best word to describe it. I still think it’s a necessary institution for us, but I also think it’s badly in need of overhaul, particularly where its powers of investigation are concerned.

Second, ethics. In 1987, the NAR administration published two Codes of Ethics for parliamentarians including ministers, and for parliamentarians including parliamentary secretaries. (Why the title overlap I cannot say.) After 30 odd years, they need to be dispassionately reviewed. And adhered to.

Among other things, they should in my view set out how a minister should act in the event he or she is arrested, even if not yet charged. In the Westminster system on which we claim to have patterned ourselves, a British minister arrested on suspicion of criminal activity would be expected to resign forthwith.

To say that one is “innocent until proven guilty” may be legally correct, but good governance goes beyond the law; crucially, it embraces ethical behaviour. Someone occupying a position of such public trust and responsibility as a minister (or a judge) must, in the national interest, constantly live up, and be seen constantly to live up, to the cardinal requirements of that position; a proper example must be set, especially to the young.

The mere fact of arrest, as in the recent circumstances, should therefore trigger an immediate departure from office. As Winston Churchill said, MPs must always place country above party and constituency.

Third, scrutiny of government grants. To what extent, if at all, do we oversee the use of government (taxpayers’) monies given to institutions? Do we even first check the bona fides of such institutions? What role does the ministry’s accounting officer play? (Incidentally, what about the Darryl Smith matter?)

Fourth, bail. My comrade Martin Daly has for years been questioning our bail procedures. This is clearly a matter of national interest, especially for the less well-off, who find themselves on remand for ages because of their inability to meet bail conditions. Might their frustration be a factor in the hits called on prison officers?

Fifth, vetting of candidates for office. That this should have become an issue in 2019, nearly six decades after we gained political independence, tells you a great deal about our continuingly and damagingly poor quality of governance. We have preferred to operate by party loyalty, personal and financial relationships, and vaps. We can and must do better.

Barack Obama’s White House transition team prepared a lengthy questionnaire for those desirous of working in his administration. We – civil society and the political class – should look at it to help us draw up our own list (which in my view should include a polygraph test).

Why civil society? Because it must by now be obvious that many decisions made by politicians zealously guarding their party ramparts have not benefitted the population as a whole. Ministerial office concerns the nation, not merely the party. Remember Churchill.

I have two more suggestions. One is that monitoring of the individual continue after he or she accedes to office. That might sound like George Orwell’s intrusive Big Brother, but, as we know, the world these days is what it is. The second is that prime ministers maintain a shortlist of vetted alternative names as possible replacements for incumbents. That should help avoid incidents like the Simonette stumble.

And let’s not forget the judiciary. The Express and Ralph Maraj have requested Justice Gillian Lucky to respond to a publication purporting to be a transcript of her words addressed to someone. In an apparent reaction to the request, the judiciary issued a non-response. But where is Justice Lucky? Only she can shed the light of truth. May we hear from her?

Comments

"Are we learning lessons?"