The future of NJAC

This is the third part of Newsday’s series looking at the National Joint Action Committee’s (NJAC) 50 years. The organisation, as was detailed in the last two articles published on July 10 and 14, shaped a new kind of TT in the 1970s and 80s. But has that new consciousness lasted into the 2000s and beyond. Is NJAC still relevant? The last two parts of this series examines NJACs role in the TT and beyond.

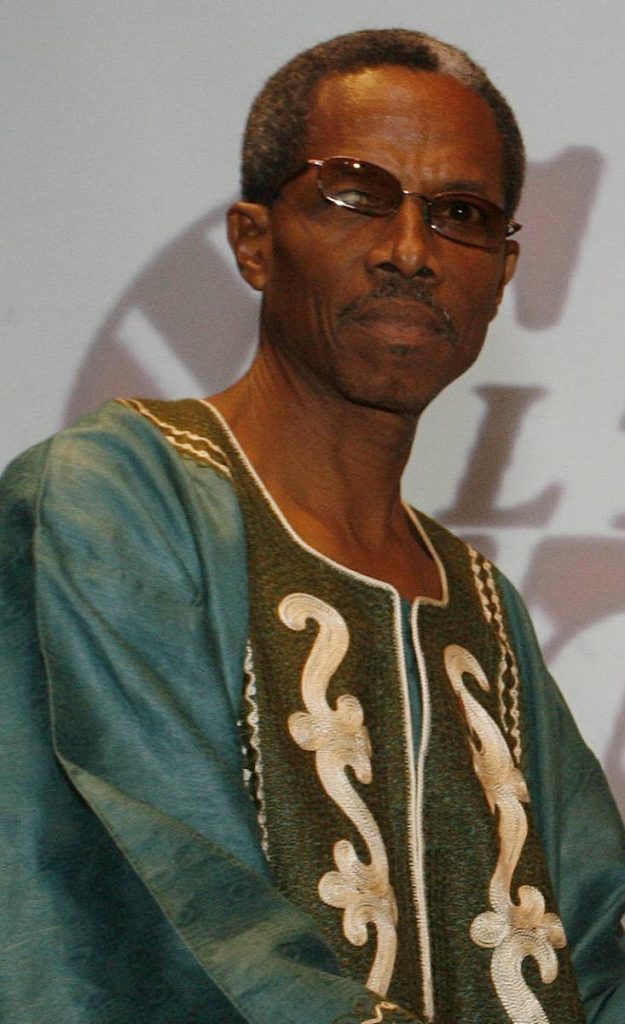

Some might say from its height in the 1970s to now, NJAC is but a shadow of itself. Embau Moheni, the organisation’s servant president, agrees that the party and organisation is not as prominent as it once was but he does not believe that it has lost its way.

He believes that NJAC’s principles are everlasting and so will contribute to the party’s longevity.

The organisation’s principles, which many of its members have lived by, inculcated and internalised, he said, have been clearly enunciated. Some of the party’s principles are: the political system must be outside of control and manipulation; political systems must be structured to involve the people as the supreme authority in the decision making process; the political institutions of the new society must grow out of people’s conscious creative effort to build institutions by which they can govern themselves; labour must be organised as a positive force of economic development; work must be seen as a right of every citizen; economic security must be guaranteed to all; different cultural expression must contribute to the building of a united nation and the society must, as a concept, believe in the equal worth of every one of its members.

NAJC’s principles also placed emphasis on Caribbean unity and the legal system maintaining the “wholesomeness” of the society.

The organisation’s philosophy, he added is so closely intertwined with “the pursuit of human development, human progress, justice, equality...” So influential NJAC has been on TT’s consciousness, Moheni said, many of its members would come to the organisation and gave yeoman’s service without a cent in pay.

Its popularity and influence subjected it to “attacks” which left the organisation in debt and contributed to its lack of prominence.

“Some of our members have been incarcerated, victimised, our national headquarters was burned out, bombed out as a matter of fact...” This happened in the 1980s.

Moheni said this was the only property NJAC owned. The Hermitage Road, Gonzales headquarters was not insured and the organisation spent years paying off the mortgage. NJAC, he added, also printed its own newspaper from that location and so lost its printing press when the space was burnt.

“So all those years when people weren’t hearing NJAC’s voice, we were just struggling to pay debt.”

Moheni said the organisation did not get out of debt until 2007-2008. “It was a very harrowing experience.”

While many believe that NJAC is all about Black Power, Moheni said its vision has always been about national unity. This, he said, was Makandal Daaga’s vision even from Pegasus.

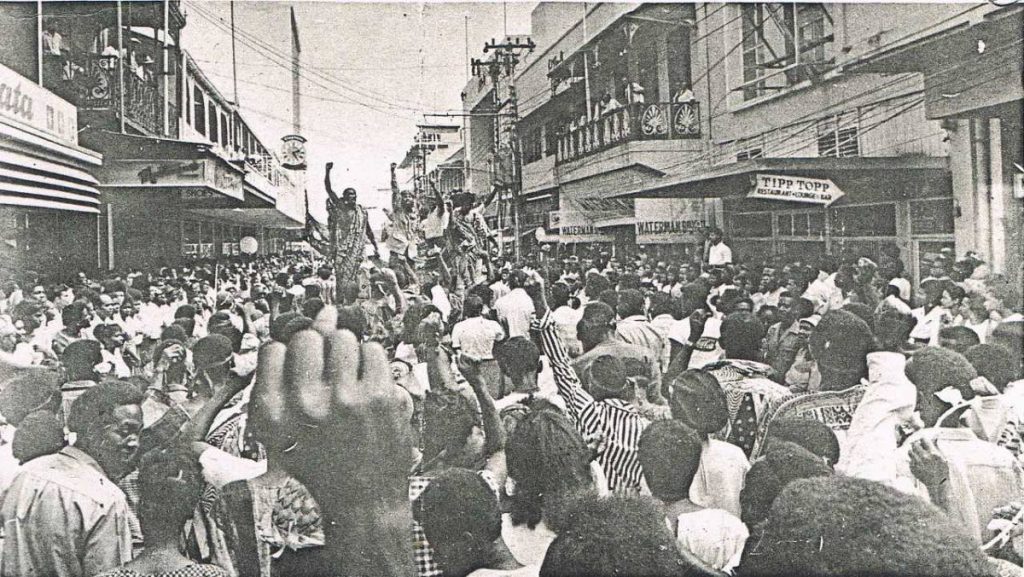

Its march from Caroni to Couva was a perfect example of its attempt to unite the two major races “away from race politics.” The march from Caroni to Couva took place on March, 12, 1970. In a 2016 anniversary piece on wired868.com, Moheni said, “In its quest for people’s power, NJAC recognised that national unity was absolutely essential for true independence. From the very outset, the banners at the head of the demonstrations read “Indians and Africans Unite Now.” This climaxed in a call for National Unity on 12 March 1970.”

Moheni believes that NJAC “was doing fantastic work” and made “fantastic achievement” in that short period in 1970.

Moheni also credited the organisation as one of many firsts. He said NJAC was the first party to challenge all the other parties to have a minimum of 25 per cent female candidates in the 1981 general elections.

“We were an advocate for women’s participation in politics.”

NJAC dispensed with the idea of men in front and women behind, saying “they are to be side by side.”

“A lot of the rhetoric that is used today came out of 1970,” Moheni said.

He added that the organisation saw the nation as a family and developed the greeting "brother" and "sister."

NJAC, he added, always stood and continues to stand for national unity, and in 2010, when NJAC became part of the People’s Partnership led by the Kamla Persad-Bissessar-run UNC, it was an opportunity “to strengthen that cause for national unity,” and Daaga saw being a part of the Partnership as an opportunity to fulfil that dream.

Asked if the organisation was still up to political marriages and coalition government, Moheni said it was open to always putting the national interest first.

“We sit, look at the landscape and see what would be best for our people, what would be the best for TT and national unity.”

Although not prominent, NJAC is still politically active, Moheni said, and will be contesting the 2020 general election. And asked how the party planned to contest it, he said, “Where there is a will, there’s a way.”

Asked if other political parties have approached it for collaboration, Moheni said no, not at this point.

While he does not see the party as a fallen one although, he admits the membership is less than it would have been.

NJAC is working to re-instil the values that could engender a more humane society and meets regularly, weekly and bi-weekly at its Duke Street, Port of Spain headquarters.

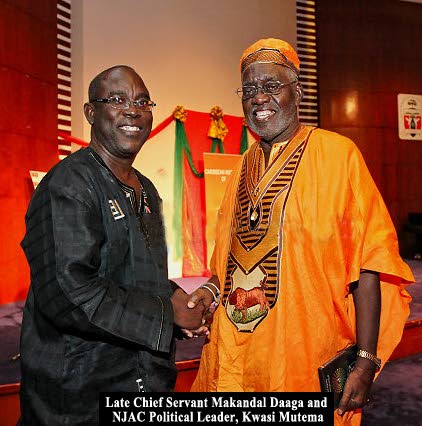

There is new leadership at NJAC’s helm with servant political leader Kwasi Mutema. He became its leader after Daaga’s death in 2016.

Although it has only been an interfaith service so far, Mutema has promised its 50th anniversary will be celebrated throughout the year.

He too does not credit Black Power as the cause for NJAC’s formation. He agreed there are diverse opinions among those actually involved on the use of the term Black Power, but shares the belief that the term Black Power was used by the media.

For Mutema, a major focus of the revolution was to address the balance of power, and a major factor that determined that balance was ethnicity and skin colour: “The questions of the whites having dominance within the society and the blacks suffering,” he said with black being defined as people who are non-white, including Indo-Trinidadians.

The movement, he added, empowered both Afro- and Indo-Trinidadians. He quoted Prof Brinsley Samaroo as saying the revolution had a great impact on the Indian population and resulted in their accepting their traditional names and way of life. Indo-Trinidadians, Mutema said, were giving up their traditional names and adopting English names; the revolution helped them to accept their heritage, and 1970 was able to give the Indian a new kind of motivation and respect.

He also agreed with Moheni that Daaga’s original intent was not political activity, but he had a strong sense of social awareness, concern and desire to serve. Like Moheni, he does not think the organisation but the country has lost its way.

“The society was not given the chance to accept fully what NJAC had to offer, in terms of its ideas and programmes and so on.”

He said NJAC’s approach was one of political education. “I think that is what people admired. When you left an NJAC meeting you left uplifted.”

The public, by and large, appreciated NJAC, he felt, since otherwise it would not have had 1970 or the years after.

He said when the party first entered electoral politics in 1981, most people felt NJAC had the best ideas/policy but was stopped by a “string of 'buts,'” such as people feeling they were wasting their votes.

He also said there was propaganda that went along with that.

“When you look at a lot of the predictions that NJAC made, during those early years, we are seeing them unfolding before our very eyes today,” Mutema said.

He said many people are now alarmed by crime and the types of crime taking place, but this was predicted by Daaga years ago.

He said the party also offered solutions to many of the problems faced by TT today. Asked if it had a space in today’s TT, Metuma said yes, NJAC’s message still had a very relevant place.

The party has also been preparing for the future by building a second tier of leadership, but Mutema said while the organisation has a “vibrant youth” arm, its youth component was not “strong enough.” This was identified in a recent strategic planning session.

“There is need, we feel, for greater balance in terms of having a greater youth presence.”

Asked if the coalition was the beginning of the end for NJAC, Mutema said no, and that its purpose “was another vehicle for bringing about national unity.”

He too said the party was open to future political marriages, and national unity was a major concern and mission of NJAC.

“Unless this country achieves that objective of achieving real national unity, I do not think we will ever be able to go forward as a nation in the true sense of the word.”

Comments

"The future of NJAC"