Black Power and NJAC

The first article in a Newsday series on NJAC over its 50-year existence, published on July 10, looked at how the organisation came into being. It was one of the groups whose work led to Emancipation being declared a national holiday on August 1, 1985. Emancipation Day was precipitated by several factors among them the 1970 Black Power Movement of which NJAC was a major player– but past and present members have different views of its meaning. This is examined in today's feature.

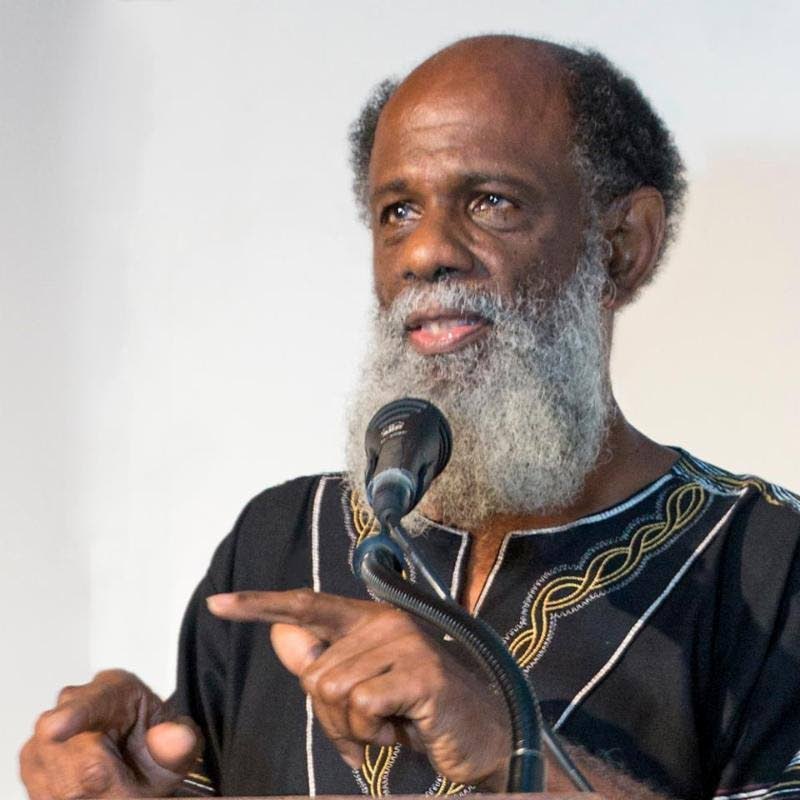

While some might say that Black Power was not the basis for NJAC’s formation nor the movement (also called the Trinidad and Tobago Revolution by NJAC), for Khafra Kambon, Black Power was its essence.

“The organisation did not immediately form and say, 'Let us be a Black Power movement,' but our language as radical people at the time was definitively Black Power, shares Kambon, an NJAC member at the time.

“Everything was coming out of the Black Power movement. Every meeting...the symbolism...the fist in the air. The shouts of power. Every single meeting was ‘Power, power, power. Black Power, power, power.”

Kambon, head of the Emancipation Support Committee, has since left NJAC –he did so around 1984/85, and believes the organisation has lost its way.

“If it could deny Black Power as its source, I don’t mind if somebody wants to say we are not in that again. We find that is foolishness. We were young. We were foolish, whatever. But to deny it...it is really a shock to the system to me.”

If NJAC had denied Black Power in the 70s, Kambon would not have been a part of it.

NJAC, he said, no longer projects revolution, whether it is Black Power or anything else.

The “denial” of Black Power comes as the party and its leadership say the movement was for a “new and just society” and the revolution was the TT Revolution, explains Embau Moheni. He was the party’s former deputy political leader, now its servant president after the April 28 internal election.

Moheni, by contrast, said the organisation is quite convinced that the term Black Power was introduced to “alienate the movement from the other ethnic groups in the country” and the use of the term was a “masterstroke by its enemies.” For Moheni any discussion about NJAC’s start should begin with a group called Pegasus, since Pegasus shaped a young Makandal Daaga.

Pegasus was a “service organisation meant to put the country on a pathway to true independence” and encompassed cultural, economic and social aspects.

This group was started as Daaga found that there was no real mood of celebration around TT gaining its independence in 1962. Moheni said when Daaga attended an independence party and calypso was “bawled down” by the crowd, Daaga became so alarmed that he and his friends left the party and began to discuss what independence was all about.

Through Pegasus, Moheni said, Daaga was able to assemble “75 of the young brilliant minds in this country in different areas, most of whom have contributed significantly to national life then or afterwards.” He named people like former minister of finance and Central Bank governor Winston Dookeran, media professional Ken Gordon and masman Peter Minshall.

Moheni added that kind of “brain power” behind Daaga “created concern” where the Eric Williams government was concerned.” He said Williams saw Pegasus as a group that could challenge him even though the “chief servant (Daaga) had absolutely no intentions to build a political agenda.”

There were a number of events between Williams and Daaga, Moheni said, which pushed Daaga down a political path.

He recalled being told that when Daaga asked for Williams’ blessings for the construction of a national stadium, Williams promised to return to him within two weeks, but instead “went straight to Parliament and said the government was doing it.”

Pegasus, Moheni said, and then came up with another project called Project Port of Spain, getting together with “businessplaces in Port of Spain, engineers, architects, designers...to redesign Port of Spain along the lines of a modern city.”

But when Dagaa was about to launch Project Port of Spain in City Hall, Williams called a mass meeting next door in Woodford Square.

By then, Moheni said, Daaga had had enough and decided he was going to “teach Williams a lesson.”

Although Pegasus died a natural death, Moheni believes that it was at this point that Daaga’s focus began to shift.

This shaped the Daaga that became UWI guild president and also led the revolution which saw thousands march throughout the country and the death of protester Basil Davis.

But Kambon disagreed with this saying that Pegasus could be credited with the formation of NJAC. Pegasus, Kambon agreed, shaped Daaga, but said it did not lead to the formation of NJAC. Kambon said Daaga became radicalised when NJAC came together and Black Power was the basis for its formation because of “the environment of the time."

He was also “absolutely stunned” by hearing that Black Power was something imposed on the group by the media. The first time he heard that was 20 years later, Kambon added.

Documentation, he added, was being prepared to give Black Power a full ideological definition and he still had the papers.

He emphatically denied that the media gave the movement the term, Black Power. He said the organisation started to break up in the early to the mid-1980s and wished not to discuss the reasons for that.

“It has become an organisation that is working on issues for people which are quite relevant. Have an education programme going. Working in the culture...”

Kambon said he does not know the organisation from the inside anymore but saw a major challenge with the death of Daaga, because he had “a national image, and therefore, based on his image, they could have gone out and attracted certain resources.”

The actual revolution began on February 26, 1970, when one year after the Sir George Williams University sit-in in Canada, NJAC and other groups held an anniversary demonstration in Port of Spain. The then group of approximately 200, according to an article by historian Jerome Teelucksingh, entered the Roman Catholic cathedral and had a sit-in.

The group made their way to various spaces throughout the city such as the Canadian High Commission, then on South Quay; Royal Bank of Canada on Independence Square and along Frederick Street.

At the end of the march, a meeting was held at Woodford Square. “Nine of the leaders of this historic march were later arrested and faced charges, including a breach of peace and disturbing a place of worship,” Teelucksingh’s article said.

When the nine leaders were released on March 4, 1970, the first of several “massive demonstrations” were held, it added. “Thousands of supporters, including Black Power groups from rural and urban areas in Trinidad and Tobago, converged outside Parliament. They gave the traditional Black Power salute and shouted ‘power,’” the article said.

For that month of March, Teelucksingh wrote, “Black Power marches and protests continued throughout Trinidad and Tobago, from which there were minor skirmishes with the police, but this soon changed when a protester died.”

It added that Davis’ killing “mobilised persons (sic) from all walks of life.”

Both the revolution and NJAC changed TT. Raffique Shah, then lieutenant in the army who led a mutiny, said in a phone interview, NJAC and, moreso the revolution, had an impact in the sense that it made people aware.

He said prior to the Black Power movement people (meaning the non-elites, as the elites were mainly white) were aware that they were not getting, out of independence, which was eight years before, what had they had expected.

These expectations were in the sense of having control of the economy, and by that Shah meant people holding the management and decision-making positions in the public sector.

He said in the private sector people were “shut out of certain levels of responsibility even though they were qualified.”

The movement, Shah said, brought those issues “front and centre” and demanded that people take their rightful places.

“So the movement put those issues: ownership, control, policy-making, decision-making in the public sector and certainly positions that they were capable of handling in the private sector, the Black Power movement put those on the agenda and in its aftermath the government was literally forced by the weight of public opinion to give in to many of these demands.

“And we saw the promotion of local people to positions of influence in big industries. Also in commerce you started seeing more non-white people in managerial positions than we had ever had before,” Shah said.

The banks, he added, were the windows to seeing “in all its nakedness” what obtained pre-1970.

Shah said the only locals working in the banks then were the fair-skinned ones, whether they were fair-skinned Indo or Afro Trinidadians, and the local whites.

“Of course, later we discovered that those jobs meant little by way of control but it certainly meant more faces in the institution like the bank,” he added. Also the movement meant some political cutting back. He said, for example, in the then PNM-led government there was the removal from ministerial portfolios from people like Gerard Montano and John O’Halloran.

Shah said, culturally, the local culture, which was “pushed into the dark”, finally started emerging and becoming mainstream. This also ushered in the “ascendency of the steelband.”

“I mean it was there all the time. But its ascendency, in the frontline of the culture, again, that came out of 1970,” Shah said.

These happenings cemented NJAC and its leader, Daaga, as an important part of TT and its history.

Like Shah, Moheni said, the TT Revolution was a “mass movement that affected so many different areas of life, nationally as well as regionally. And that drew the attention of very citizen.”

In 1970, a then 16-year-old Tobagonian – Moheni – became a member of NJAC and took part in the demonstrations because for him “it was a just cause.”

“And justice is something that is very close and dear to me.”

Comments

"Black Power and NJAC"