Elitism or insanity?

We obsess over replicating the aesthetic of the grassy lawns surrounding grand, old English country houses, but the peasants of the time could probably only gaze in bewilderment and resentment at how people could use so much space to grow grass instead of for farming or some other economically-productive use.

The ability of individuals to buy land and not use it efficiently or for productive means is a luxury of the well-to-do. A system of land-use regulations (zoning), like the one we utilise locally, that insists upon using land in that way, is elitist.

Our zoning system shares many similarities with the typical model in the United States known as Euclidean Zoning, named for the US Supreme Court Case of Euclid versus Ambler. Core similarities include:

Specific standards that dictate the distance of buildings from property boundary lines (setbacks); the height and number of storeys; the allowable ratio of gross floor area of the building to the area of the lot of land (floor area ratio); the maximum percentage of the lot area that can be covered by the building (building coverage) and can be paved (site coverage); the maximum number of separate dwelling units that can be housed on the lot (residential density); and more.

A nuisance-based approach premised on the perceived incompatibilities between different land uses, such as residential and commercial, resulting in large distances between places of residence and places of employment and commerce.

A bias towards a suburban single-family aesthetic, with detached homes, grassy lawns, and generous distances between the building, the public right of way and neighbours.

A preferred road network design, known unofficially as the “cul-de-sac collector model,” where local residential dead-end roads feed traffic into collector roads, which then feed into main roads, and finally into highways.

Euclidean Zoning became a tool, among many others, used to exclude poor, typically non-white, people from affluent white communities.

How? By placing restrictions on the use of land guaranteeing that only those of means could afford to use land so casually and inefficiently, and ensuring that convenient travel from that land to jobs and amenities meant purchasing an automobile.

The larger the building setbacks, and the lower the allowable floor-to-area ratio, building coverage and residential density, the more likely the suburban community was to be rich and white.

Such regulations create a perfectly wasteful way to use land. Add to that an overall development pattern that is spread out, with a low level of connectivity between roads, and is therefore much harder to service with efficient public transportation, or to bike or walk anywhere useful.

That development pattern is an experimental one. In over 1,000 years of human civilisation, it has existed on a large scale through regulatory mandates for maybe 75 years, and has already been failing in just about every way, even in the country that pioneered it – a country that is far wealthier, still manufactures vehicles, and still has roughly seven times more land space per person than TT.

It would be a dubious claim to say that the goal of zoning in TT is stratification, but the result can be exactly that. But then again, we can’t appreciate the implications of Euclidean Zoning when we refuse to recognise our system as such. Zoning is “Yankee ting,” ent?

We spend exorbitant sums of public funds on projects that entrench the car-dominated way of life; we spend money to host conferences and “training sessions” where we theorise about the problems of car-oriented development; and we pat ourselves on the back for using the words sustainability, resilience, and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in as many conversations, speeches, and press releases as feasible.

Yet when it comes to reassessing the fundamental blueprint guiding our approach to land use, we cannot seem to prioritise, justify or even discuss an overhaul of zoning regulations.

An overhaul that could ease the burden of affordability by allowing for the supply of housing to increase; begin to reshape the environment around sustainable transportation modes like walking, cycling, and public transit; and tackle economic inequality by making it easier and cheaper for people to access employment, and not spend money on buying, maintaining, and insuring motor vehicles – which are depreciating assets that we don’t manufacture and pay exorbitant costs to import.

The US state of Oregon, with far more per-capita land space and wealth than us, just recently made it legal to build duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes in places currently reserved exclusively for single-family houses.

The deafening silence on the issue would be baffling if here, silence wasn’t so golden, or should I say lucrative.

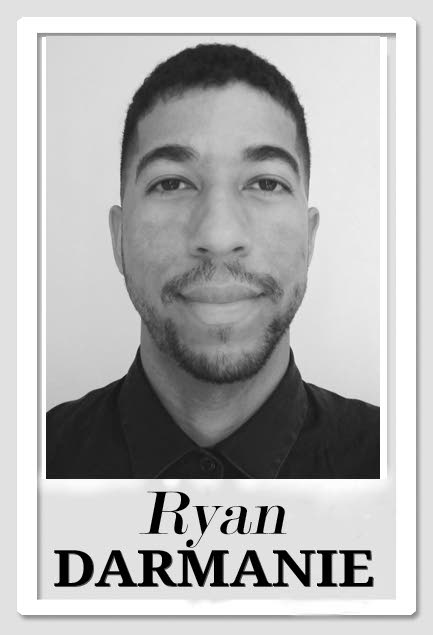

Ryan Darmanie is an urban planning and design consultant with a master’s degree in city and regional planning from Rutgers University, New Jersey, and a keen interest in urban revitalisation. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or email him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"Elitism or insanity?"