Before Stonewall

Before Stonewall is back in US theatres for Stonewall 50, I got to see the Greta Schiller/Robert Rosenberg documentary on the big screen during its first release, a time I spent much of my life walking past the nondescript Christopher Street landmark, to or from tiny overstuffed Oscar Wilde Bookshop that consumed most of my disposable income; the vogueing and hook-ups on the piers at the end; or, round either corner, Keller’s bar or Peter Rabbit’s dancefloor, which, like so many other clubs black gay men frequented, have disappeared.

I’d been living in New York almost all my short adult life, escaped rented Brooklyn rooms in older Trinidadians’ homes for a stint of homelessness, then a shared apartment in a Washington Heights on the cusp of crack. My student visa had expired, I’d left school incomplete, and made the immomentous decision that returning home as a 23-year-old gay man with no degree didn’t make much sense.

I was discovering this heady community of other black gay men through writing and activism. As I wrote in an essay-excavation of the HIV grief under which that period has since become buried, I knew that intersection of blackness and queerness “was not so much a delta or natural landmark for me, but a convenient place, like a city, to build a house: a bustling place where people were gathered and energized. And so I built, because it was powerful to see the beams reach upwards foreshadowing the roof. I knew…this particular crossroads had no co-ordinates where I came from.”

Before Stonewall historicised queer life in the United States for me.

So “you can imagine my surprise” (the words of the song itself) when during World War II’s impact on US domestic life and gender – off the screen into the theatre’s darkness leapt the sound of De Gay Young Lad from Trinidad.

In relentless innuendo (now readily accessible on Youtube), Ruth Wallis, saucy chanteuse of 1950s recordings, invites us to imagine her surprise at finding “a pansy in Trinidad” on an exotic trip which on she expected to sow “a few wild oats, but he preferred banana boats.” He was “as gay as he could be…The waves they were swishing against the shore. Like the waves swished, so did he.” She thinks to teach this shy young man lovemaking skills, but ends up discovering “the things I was trying to teach him I found him learning from some other guy…Heavens above!…Nobody knows I’m the lookout. And those other two are in love.”

I never expected, looking back at America’s queer past, to find it looking back at me.

Wallis’s tune is a constant reminder about storytelling.

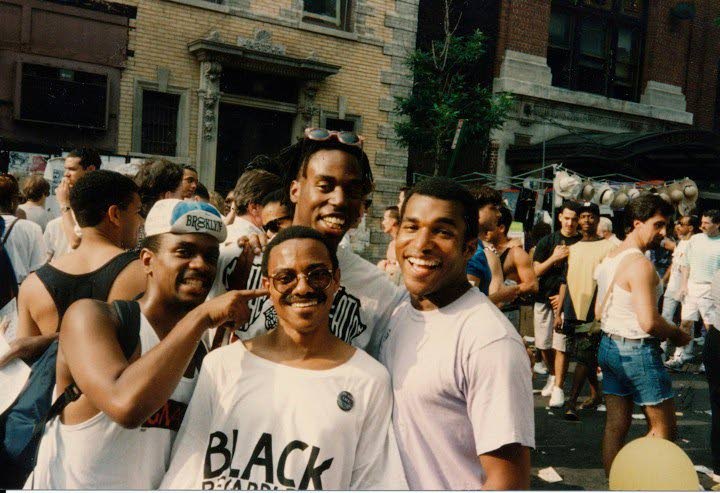

Pride parades, with so much of which Stonewall 50 was celebrated, continue to be triggering for me. I’ve felt Pride in New York transform from when I first experienced it as a raggedy, raucous space that welcomed queerness and non-conformity into a sponsored festival of binary flesh – all these men with bodies you don’t have, whose bodies you can’t have – more readily inspiring lonely shame than anything else.

But watching in my Guyanese friend’s video of the sea of Caribbean flags jump-and-wave behind Caribbean Equality Project’s soca big truck in Sunday’s World Pride parade, I couldn’t repress the tinge of regret that I’d taken a self-protecting pass.

But I held on to pride that I helped transform Pride too. If it wasn’t me, it would’ve been someone else.

But in maybe May, 21 years ago, Godfrey Sealy was living with HTLV-I and sitting at my Brooklyn dining table, with us preaching to him about all that Caribbean LGBTI movements ought to be doing differently. Someone – I think it was Gail from Tobago – asked what we’d done for ourselves as Caribbean queers in New York. And weeks later we had put a soca big truck up in the people’s Pride Parade, down Manhattan’s Fifth Ave to Greenwich Village, behind a bright-yellow banner that Leslie, who used to beat in Phase II, led us in making, saying “Caribbean Pride.”

The truck’s a fixture now. But then Caribbean folks were used to being queer outsiders, looking on at the parade. And suddenly they were watching ourselves all in it. The stories were breathtaking, beyond our imagination. The woman who heard the beat coming from the distance whose pores raised recognising the soca, who left the friends and the corner she was to meet them, to follow us. The Garifuna man wining atop the truck realising it would pass his work site and he wasn’t even on the other side; refusing to budge. The person who disobeyed the officer, scaling the barricade the minute he’d turned his back.

It was the year of Who Let the Dogs Out. I still remember its barking echo off the canyon-like buildings as the oversized vehicle inched along the narrow street past the Stonewall Inn.

I could keep telling these stories.

Comments

"Before Stonewall"