Murder, Trinidad and a novel

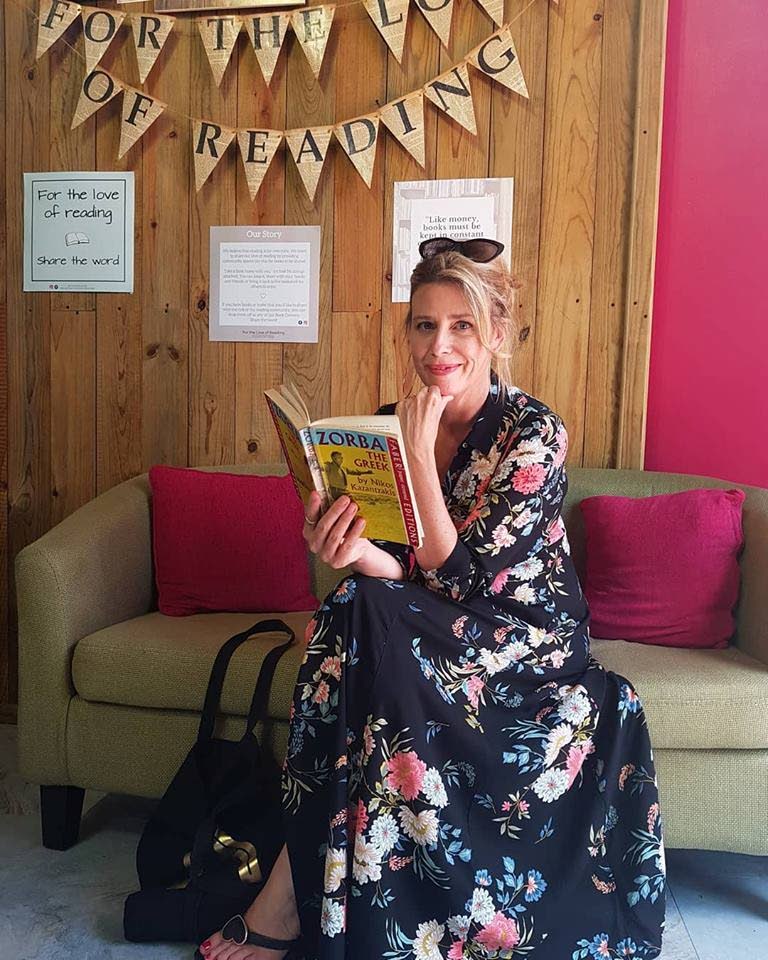

AMANDA SMYTH is a Trinidadian-Irish writer. This is the second and final part of a talk she delivered recently to MA students at Birmingham City University in the UK.

When my father was dying, I came back to England with a few stories and some poems. I sent them out; they were published. I applied for an MA, and by then I had enough of a body of work. It didn’t matter that I didn’t have a degree.

For the first time in my life I knew what I wanted – to be a writer and to be a good writer. To get better.

At the University of East Anglia, Ali Smith was my lecturer. Over a tutorial, she handed me the stories I’d given her and said, “Right then, you can put these in your book.”

I said, “What book?”

She said, “The book you’re going to write.”

I’d never thought about that. I thought only about getting the stories into good shape. I was naïve.

I learned some things at this time. It was easy at UEA for expectations to drift into fantasy. It was easy for students to get carried away with ideas that the work will soar; that it will come easy, and pretty much make itself.

Expectations based on illusion lead almost always to disappointment. But expectations based on the work itself are the most useful tool a writer can have. What you need to know about the next thing you write is contained in the last piece.

Your work is always your guide. There is no other such work and it is yours alone. Your fingerprints are all over it. It tells you about your discipline, your techniques, your working habits. Your willingness to embrace. Your capacity to reach. The lessons you are meant to learn are in your work.

But here’s the thing: to see them, you need look at the work clearly, without judgment, without need or fear, without wishes or hopes. Ask your work what it needs, not what you need. If you set aside your fears and listen, the way a good parent listens to a child, it will tell you.

I left UEA with a collection of short stories. I found an agent. After six months, the stories were almost signed by three publishers.

But the short-story market was tough, and they were eventually turned down.

I was back to square one. What was I to do?

My agent told me I must write a novel.

About what? A novel? I can’t write a novel.

I took a job working for an internet company, and when I had time, I delved back into my memories, and thought about the stories I had heard as a child in the veranda. I knew only this: I wanted to write about Trinidad. It was a place that affected me deeply.

I decided to write about the murder of my great-grandfather and I imagined his murderer. I remembered the stories my grandmother told me about her uncle dreaming of buried treasure. The bullet wound my mother had talked of. I found photographs of the old estate, the citrus trees, the donkeys, the scorching Trinidad light.

It took five years of working on it on and off. I had no idea it would be so difficult. I couldn’t get the story quite right. It was much harder than I expected.

When it came to my next book, I was unsure what to write about. I knew that to spend years writing something, it must matter. It must excite me.

At the time, Trinidad was dangerous – there were kidnappings, break-ins, brutal killings. By chance I met an ex-police officer from the UK who was recruited to work there. I decided that I would write about this.

I drew upon an experience I’d had when I was living in London, when a group of men came to a flat where I was house-sitting and beat on the door with hammers and drills. It had affected me a lot.

I became fascinated with the idea of danger. I took a job in a police force as a PA to a chief superintendent. I waited each morning for criminal reports to land on my desk so I could type them up.

I remember a man who worked in “estates” coming to me one morning. We had never spoken before. He was in his thirties, fine-looking. He sat down and told me about his journey to work that day. How he had to pull over in the dawn light, stop at the brow of the hill, to steady his galloping heart. He was sure he was going to die.

He looked up and saw the oak tree, the light, the familiar skyline. He knew he was going to be okay. He started the engine and drove away. Astonished by his honesty, I wondered why he was telling me.

We never spoke again.

A year later, I took this scene, and I gave it to my protagonist, Martin, in A Kind of Eden, when he is close to having a breakdown.

As writers we listen, we hear stories, we steal them, we put them away in notebooks and use them when we need to.

We must be curious. Apart from anything else, it makes the world even more interesting. I would like to encourage you to be curious about other people, write down things that capture your interest, don’t let them get away.

I found a note about a woman I knew when I was young. She had a hand curled like a claw from a childhood disease. I used this in the novel I’m working on now. I gave her the same name, Elsie.

We must remain as curious as children. We must pay attention. Our lives don’t have to be exotic. Strange and wonderful things can happen in the ordinary.

When I go back to Trinidad I see every trip as research. I take photographs with my mind. A man coming towards the car with no shirt and eyes that look crazed. A vehicle burning on the highway. The sunset, a sky as swirly as ice cream. I hear of the ghost of a young girl once seen floating in the hills of Central, and I think: I’ll use that, too.

In the last few years, my mother has been talking about my great-grandfather and how he invested in an oil well that blew up and killed 17 people. They were partying in the Queen’s Park Hotel while gas was leaking out. It was one of the worst oil disasters in the Caribbean. A cousin saw it in a prophetic dream.

I decided to write about this – this real story. I’m using things that have been in my memory box for 40 years or more.

We all have memories. We all have an inner world, an interior life we can explore and mine and exploit. You have your version. You have this all at your disposal.

After a while, we become better attuned to listening to our instincts. If an idea comes to watch a particular film instead of sitting at your desk, then watch the film. Go to an exhibition if it will feed into the work. Keep yourself inspired, excited by the world you’re writing about. Work hard. Keep your toolbox stocked.

And when you think you’re done, work harder. Don’t give up.

When I was 18, I lost my beloved cousin in a car crash in Trinidad. I wrote a prose poem about her death, and it came out of my fresh grief. The poem was good. It landed quickly on my page, and my mother said, “How wonderful, let’s send copies to the family.” My mother had it written in special calligraphy and put it on the wall in her house.

Years later, I brought my mentor, Wayne Brown, home for tea. I saw him stop in front of the poem, hands in his pockets, head cocked. I felt pleased with myself. I waited to hear what he thought.

He said, “Well kid, you’re not as good as you could’ve been.”

“What?”

He said, “This piece of writing here. You were how old? Nineteen?”

“Yes.”

He said, “Well, if you’d kept writing, and working hard, you’d have been something else. But you left it alone, the writing. You wasted time. It doesn’t get better by itself.”

If only it did get better by itself. But we know, it’s only through practice, through reading and writing, and reaching – reaching to be the best that we can be – that we get better. Through dreaming. Through imagining. We must read books that make us gasp.

To live a writer’s life is to feel things deeply. Isn’t that the most important thing we can do? Feel alive? Engaging our senses as much as we can – touch the tip of a rose, breathe its scent; watch rain sliding down your window; a taste of hot bread and cold butter; the feeling of silk on your bare shoulder; the sound of a baby wailing; a rush of cold sea on your sandy toes.

We can allow ourselves to feel things fully, to experience them fully, and to see things in Technicolor. Even when they are terrible. And even when they are terrible, we write about them. We find the words. We craft our sentences. We make sense of them, and out of our pain we make meaning.

Being dreamy doesn’t mean you are undisciplined. For me, and for most writers I know, they are extremely disciplined. Writers need a routine of some sort. It’s important to have a schedule because there are certain hours when you’re at your desk, your muse knows how to find you. She knows where you will be, say, from ten to one, so she doesn’t have to go out to find you. She knows at that time, you, the writer, will be at your desk.

She might not always show up. But then again, she might. And she may arrive with gifts.

A novelist friend of mine told me most of his day working is spent staring outside the window. An onlooker might say, “What on earth is he doing?” As writers we give ourselves permission to do this very thing, and allow ourselves to dwell in the place of imaginings and make-believe. And what a wonderful place that is.

Comments

"Murder, Trinidad and a novel"