One nation under Zuckerberg

BitDepth#1203

THE RECENT announcement of a cryptocurrency architecture built by Facebook with significant buy-in from other major partners might seem to trigger concerns about the social media giant’s future ambitions.

Libra, the digital currency proposed by Facebook, has already won support from powerful supporters, including Uber, Spotify, eBay, PayPal and Visa.

Facebook already has the numbers associated with an independent country, with two billion users, even discounting bots. It has a significant presence in most countries on the planet with a fluency of communication exchange that exceeds even that of the most aggressive embassy.

Now the company/virtual nation is ready to create its own currency.

According to the Facebook whitepaper on Libra (http://ow.ly/HE0F30p0ek2), “Libra is designed to be a stable digital cryptocurrency that will be fully backed by a reserve of real assets – the Libra Reserve – and supported by a competitive network of exchanges buying and selling Libra.”

In the wake of increased public scrutiny of Facebook’s operations and its notorious privacy lapses, Libra won’t, therefore, be the Facebook dollar. There will be a subsidiary company, with equal voting power divided among the companies that join up to provide the seed capital to back the Libra, set at a baseline of US$10 million worth of Libra tokens per member. Founder members must also meet two of three possible criteria, have a market value of US$1 billion, reach more than 20 million people a year or be in the top 100 businesses in their industry.

The plan is to have 100 founder members of the planned Libra Association, the agency governing the digital currency, by a planned launch date in the first half of 2020.

Libra cash investments, the white paper notes, “will be backed by a collection of low-volatility assets, such as bank deposits and short-term government securities in currencies from stable and reputable central banks.”

Libra intends to offer low transaction costs and fast transfers to users, but any returns on the reserve will be used to provide dividends to investors and to pay the costs of running the system.

Users get convenience, but no return on any money that lingers in the system.

Facebook calls it digital currency, but that’s a bank.

The Facebook White Paper on Libra concludes by restating the plan in blunt terms: “A stable currency built on a secure and stable open-source blockchain, backed by a reserve of real assets, and governed by an independent association.”

While aspirational, that statement should send a cold and breezy chill through anyone who was around when Facebook itself was introduced as a way for “friends to communicate.” If the 15 years since Facebook was founded have offered any lessons, it’s that simple, noble goals have unintended, world-changing consequences.

Were there any indication that Mark Zuckerberg, his leadership team and indeed anyone at Facebook had learned anything over that time, Libra wouldn’t seem so alluring and terrifying all at once.

A currency exchange that tracks closely to exchange rates for local funds that works in near real time is an admirable goal, but it brings a range of hazards for the banking sector as well as governments hoping to control the value of their local currencies.

And those are just the most obvious concerns.

The last time that Zuckerberg had a good idea, it was to help friends connect and chat – and he came close to breaking journalism completely as an unintended consequence.

Back then, he wanted to build a better chatroom. Now, he wants to change the fundamentals of money.

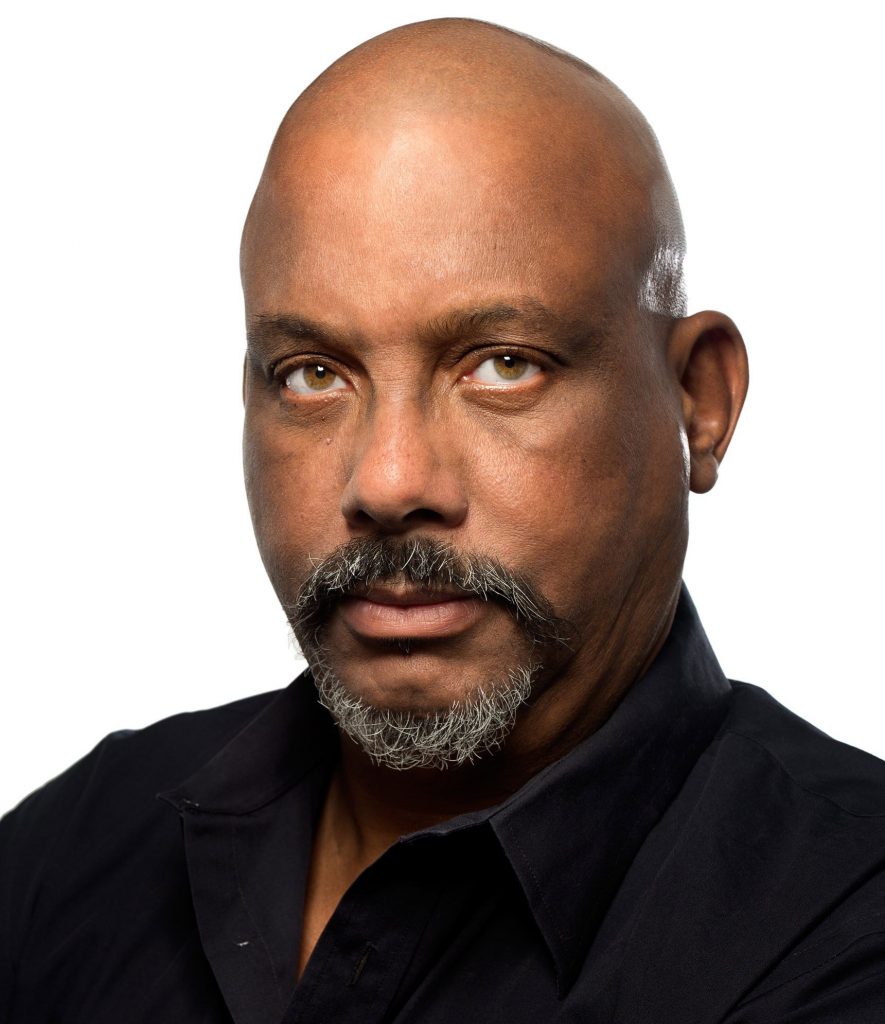

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"One nation under Zuckerberg"