Wolf at the door

AMONG Marlon James’ first encounters with a wolf was one that happened when he was six.

Not a real wolf, mercifully, but something more terrifying – the creature that appears in Little House in the Big Woods, the children’s book that made him want to write: “There were no roads. There were no people. There were only trees and wild animals who had their homes among them. Wolves lived in the Big Woods, and bears, and huge wild cats. Sometimes, far away in the night, a wolf howled. Then he came nearer, and howled again. It was a scary sound.”

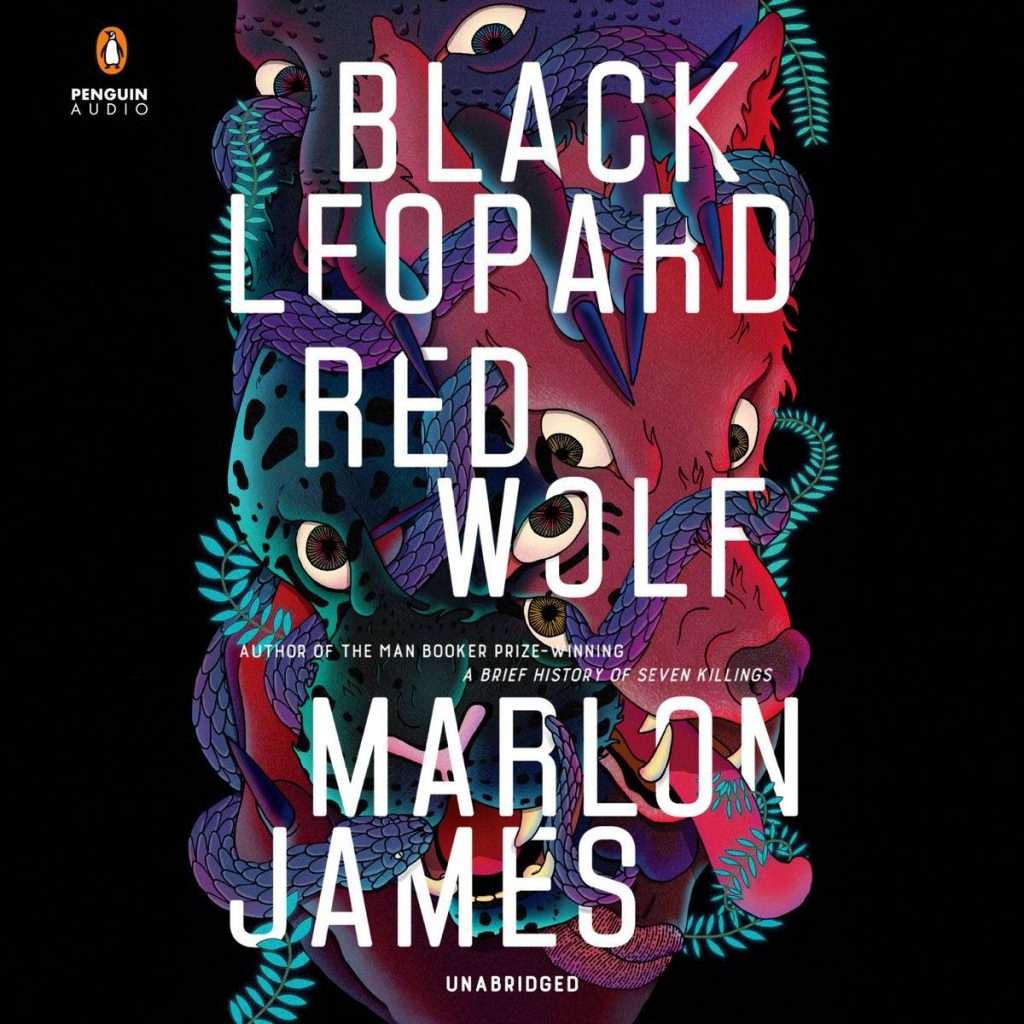

Four decades later, James has published Black Leopard, Red Wolf. Billed as an African fantasy, it is a beguiling novel that inhabits yet defies its genre. The book is an immersive experience, sometimes taking the guise of a tale of mystery and terror, sometimes a quest, an epic adventure, a drama, a buddy comedy, a coming-of-age tale.

Ultimately, like the shape-shifting leopard of its title, it resolves into the simplest of cores. Here is a love story featuring black characters. A queer love story.

“I hope readers get the sweep of an epic,” James told Sunday Newsday between a string of appearances last month at the NGC Bocas Lit Fest in downtown Port of Spain. “For me, it was about writing the type of book I wanted to read. I’m a huge fan of fantasy stories, but it must be said I rarely see anybody like myself in them.”

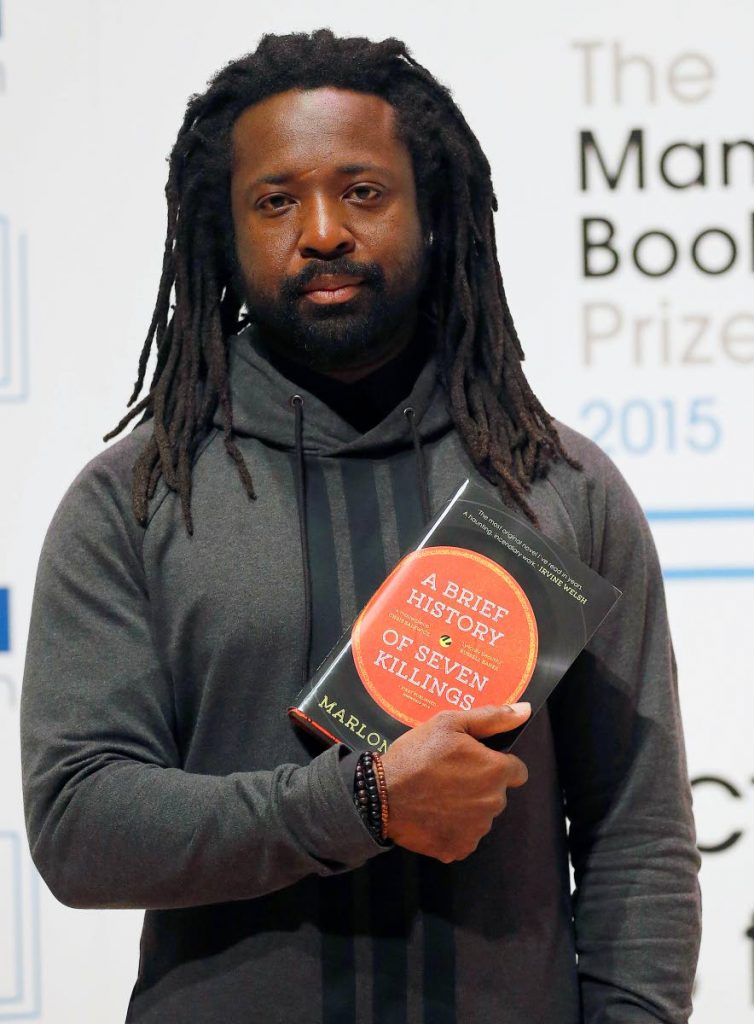

Like his previous novel, A Brief History of Seven Killings, which won the 2015 Man Booker Prize, Black Leopard, Red Wolf opens with a list of characters. Additionally, there are maps drawn by James. These prefatory materials transport us, give us a visual means of establishing the world in which the action takes place. James, who was born in Jamaica in 1970 but now lives in Minnesota, literally redraws the map.

The plot involves a slave-trader who hires a group of mercenaries, including a character called Tracker, to search for a missing boy. Instead of a rescue mission, the child is assassinated.

The facts are then put on trial. Truth is just another story, lost among a constellation of characters whose allegiances and loyalties shift like quicksand. Some things are constant.

Tracker has a powerful wolf-like nose, capable of picking up remote scents. He is also deeply in love with several male figures around him, but is only slowly coming to terms with this.

“He was the first man I could say I loved, though he was not the first man I would say it to,” he says at one point.

“I never thought I would find legitimising arguments for queerness by going back to African mythology,” James says after a quick lunch of chicken roti at the National Library on Abercromby Street. “That is the last thing I expected to find, that there have always been multiple genders, that in African traditions men were queer and were known to be queer. The fact that I could go so far back into the past and find a thing that almost justifies myself as a queer person was quite frankly a shocking and welcome surprise.

“There are people who think I was trying to score politically correct points. Or go for diversity and inclusion. No, I was just doing the research!”

A few weeks before Bocas, The New Yorker published a feature in which James candidly discussed his experience of growing up gay in Jamaica. At five, children would call him sissy. Around this time, he retreated into comics and books like Little House in the Big Woods.

As puberty hit, James tried to capitulate to the toxic masculinity around him. Students at Wolmer’s Trust High School for Boys would call him Mary. In response, he secretly practised how to “shape-shift,” to speak in a deeper voice, to sprinkle words like “bredren” and “boss” among his sentences.

Later, he fell in with an evangelical church in Kingston. At this time, the idea of writing an African fantasy with evil spirits first came to him. Meanwhile, he struggled with his gay desires. In a fraught moment, he requested an exorcism. It didn’t work. The leopard could not change its spots.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf is equally concerned with sexuality as it is with the bending of genre, the reshaping of society and the retelling of history. On the level of the sentence, it deploys a rhetorical strategy that places emphasis on language as embodying the world, and on African philosophies such as the Dogon idea of gender twinness.

Time itself works differently in this world, is associative, is dominated by the present tense.

“The child is dead. There is nothing left to know,” the book – which is meant to be the first of a trilogy – begins. In some ways, the novel’s 620 pages confirm and deny these fatalistic claims.

James litters the narrative with Yoruba, Hausa, Wolof, Fulani, and Swahili, among other languages. He peppers his plotting with suspense techniques, such as cliffhangers, moments of ratiocination in which Tracker teases out political secrets that surround the boy, and, in one instance, there is the memorable use of stream-of-conscious narration to convey the rush of sensations when Tracker has a key breakthrough. The book’s rich depictions of sexual yearning and landscape are heightened by the use of synesthetic imagery. All from a writer who infuses his prose with poetic techniques like repetition, parallelism, and parataxis (there is actually a poem at the middle of the book, and a griot’s song comprises the whole of the novel’s fifth section, perhaps in homage to JRR Tolkien).

“Whenever I start a novel, I will read poetry before I write,” James tells an audience at a Bocas panel discussion with fellow novelists Nalo Hopkinson and Karen Lord on May 4. “I particularly like War Music by Christopher Logue.” (War Music is based on Homer’s Iliad.)

At times, his novel’s story is told in a non-chronological style that betrays this poetic sensibility. Equally, the cinematographic leaps hint at the influence of writers such as Amos Tutuola, whose My Life in the Bush of Ghosts recalls the fate of a boy abandoned by his family. There are also older works looming over the proceedings such as the Epic of Sundiata, and Aeschylus’s Oresteian trilogy, which asks us to question, as Tracker does, the meaning of justice.

It’s a long book. The UK Guardian calls it “hulking,” the Independent “exhausting,” the New York Times prescribes “a little judicious pruning.” The criticism is only partly merited. Once Tracker figures out a key element of the plot, the book does appear to come to a narrative terminus.

Until, that is, James springs a remarkable closing act. By this stage, we surrender to its operatic heights.

“I wanted to write fantasy in a way in which an American or European would write fantasy, which is to look at this vast reservoir of art and knowledge and history and language and myth and legend and make something from it,” James says. “This book for me is a powerful reset. I had to change everything.” Part of the change relates to the history of British colonisation in the Caribbean and beyond.”

It was not just about researching “African stuff,” he says. “It was about reading a lot of Indian stuff too, reading the Ramayana, reading contemporary novels. Some of the novels I really went back to and read and took apart included Vikram Chandra’s Red Earth and Pouring Rain, Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red, the work of Sofia Samatar. I looked to African, Asian, South-Asian writers who have found a way forward by going back to their own myths.”

In a sense, then, redefining the story has become James’ own story. In a 2015 essay for The New York Times Magazine, he came out publicly for the first time, writing: “I teach that characters arise out of our need for them. By now, the person I created in New York was the only one I wanted to be.”

With Black Leopard, Red Wolf, he has created an elaborate conceit in which a missing boy is a symbol of the protagonist’s infantile attitude to his sexuality. In a way, the unnamed boy must be transcended for Tracker to fully emerge and to embrace, without guilt, an adult self that has left childish fear behind. After a tragic development, the book’s burning question is whether it is too late for Tracker to be happy.

“Sometimes the only way forward is through,” Tracker says. “So I walked through. I was not afraid.”

Comments

"Wolf at the door"