Chicken and chips and urban planning

At one point, the battle for the title of TT national dish would probably have been an even match between pelau, roti, and doubles. But increasingly, that title may belong to another.

For many, eating fried chicken and chips is as habitual as scrambled eggs, cereal, or sada roti for breakfast, despite the dire side effects.

Imagine for a moment that this culinary obsession had evolved differently, and with a different outcome. Imagine that this had been the history:

Some doctors in the US decided that they loved the fried food from a fast-food chain called Bob’s Delicious Chicken (BDC), and since quite a bit of Americans did too, they started a campaign within their profession to erroneously promote its health benefits. It provided everything that the body needed: protein and fat in the chicken, carbohydrates and fibre in the potato fries, water in the soft drink, and vegetables in the tomato ketchup and pepper sauce!

They were marketing geniuses, and soon many in America believed that BDC was the food of the future.

In TT, doctors, politicians, and many in the general public, being bombarded by the slick international and local marketing and media coverage, were now fascinated by the idea. A business conglomerate launched a successful local franchise.

A decision was made by the State and its technical advisers to influence the market. The State was a firm believer that BDC was inextricably linked to the nation’s progress, and the advisers had become indoctrinated in its purported benefits.

The State invested in soybean farms to grow and process the crops, and the cooking oil sold at subsidised prices to BDC restaurants. All nationals who could show proof of enrolling in BDC’s 30-year meal plan were then granted a tax deduction for their first five years of membership.

The advisers decided that the demand for BDC was going to be extremely high, so each new outlet was mandated to build a huge, on-site storage facility, as large as the restaurant itself, to keep stocks of frozen chicken, fries, and other supplies to ensure that customers were never inconvenienced.

It was therefore far cheaper to build new branches in places where land was inexpensive. Understanding this, the State then decided to invest heavily in new utilities and roads—at the expense of the maintenance of existing infrastructure—that opened up undeveloped agricultural, forested, and other virgin land on the outskirts of town, where BDC could more easily locate.

Due to subsidies and interventions, BDC’s menu items seemingly became cheaper than home-cooked food and it monopolised the entire market. People wanted to consume this doctor-approved, affordable food, and began relocating to the outskirts of towns to be closer to the source.

Those who enjoyed eating BDC for breakfast, lunch, and dinner were seemingly happy, but those who wanted some variety, or who hated the smell and taste of it, were at a disadvantage, and therefore struggled and ultimately migrated.

Eventually, rates of obesity, heart disease, and malnutrition soared. Local economic gains were transferred abroad through franchise fees. The dominance of the BDC supply chain rendered many other economic sectors irrelevant, and socio-economic inequality increased.

Later, supply of cheap oil diminished due to soil depletion and an assault on the soybean crops from pests and fungi. The BDC restaurants, and the development that they attracted, quickly ate up the limited developable land space. Water supplies grew inadequate, as people’s diets led to enormous spikes in toilet flushing. People became irritable and hostile towards each other, and the blame game began.

Some blamed ineffective medication and nutritional supplements for health woes, while others blamed it on insufficient parks and gyms for recreation; some blamed the shortage of water on the ineptitude of the State; some blamed a lack of prayer for the crumbling society; the list went on.

To grasp our current reality, substitute our suburban, car-oriented, gated community lifestyle for BDC; substitute subsidised automobile fuel for the cooking oil; and substitute parking lots for the large storage facilities.

Significant volumes of potable water are lost through leaks—which increase in number as more pipes are required to serve a spread out development pattern—and wasted in watering large, private lawns and power-washing long individual driveways and walkways.

The State and its advisers ignore the ways in which our development pattern: destroys the environment; leads to massive outflows of foreign exchange due to vehicle imports; drives our best and brightest—who enjoy exciting and intellectually stimulating places—abroad; reduces physical activity and increases rates of non-communicable diseases as walking is rendered an impractical form of transportation; and leads to social isolation, a decline of civic responsibility, socio-economic inequality and more.

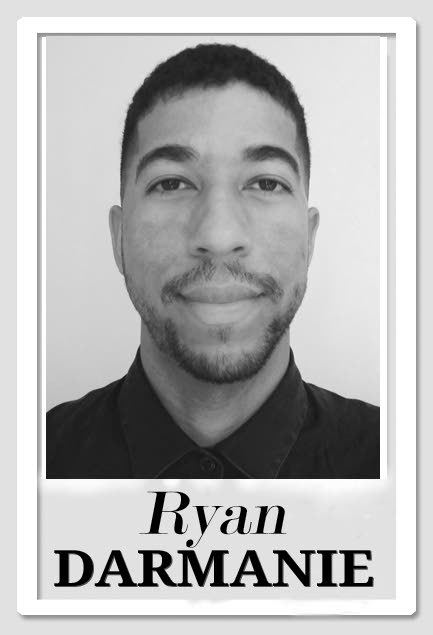

Ryan Darmanie is an urban planning and design consultant with a master’s degree in city and regional planning from Rutgers University, New Jersey, and a keen interest in urban revitalisation. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or email him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"Chicken and chips and urban planning"