Heroes and Villains

SHEREEN ALI

IS IT valid to write a scholarly biography about a person even if that person has done some terrible things? How can a biographer maintain an objective distance between a subject’s deeper significance and the biographer’s own personal feelings about some of their subject’s foibles and sins? And what about the wider public’s feelings and reactions to the areas of a biography that may straddle difficult morally or emotionally loaded themes?

These issues and more were hot topics at the May 5 session Heroes and Villains, part of discussions at the Bocas Lit Fest at the National Library, Port of Spain.

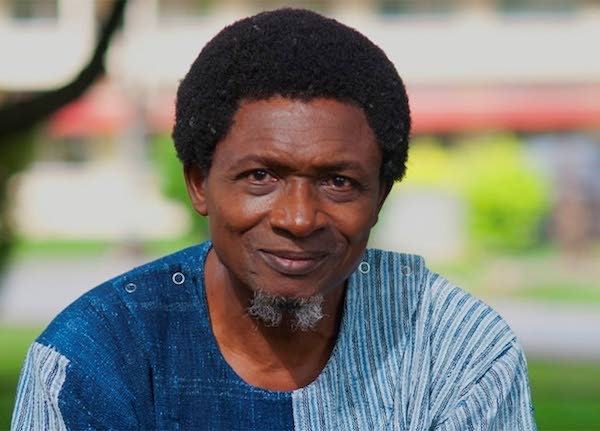

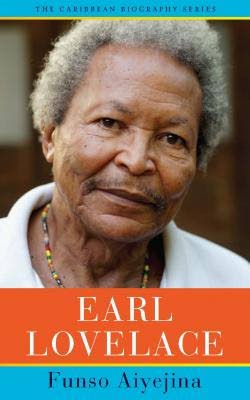

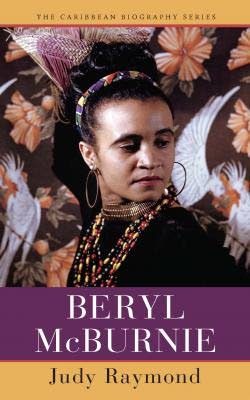

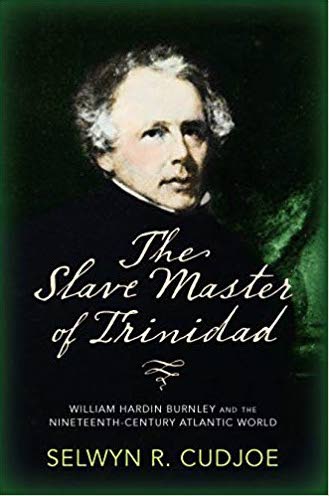

The session, moderated by Emerita Professor of history Bridget Brereton, featured writers Judy Raymond, Selwyn Cudjoe and Funso Aiyejina, authors of biographical works on three quite different Trinidad personalities: dancer and folk cultural activist Beryl McBurnie, businessman and slave-owner William Burnley and creative fiction writer and retired lecturer Earl Lovelace.

Challenges of writing biography

Good biography seeks to recreate in words the life of a person by drawing on all available evidence, combining aspects of historical research and literary skill. The Bocas Lit Fest Heroes and Villains conversation highlighted several challenges to writing any biography.

Practical problems include accessing the information in the first place; judgment calls on what aspects to focus on; whether to stick to a subject’s public life or explore their personal life too, and if so, how to get the balance right; crafting the work to be readable and relevant; and implicitly judging or framing a person’s behaviour within their own historical and environmental context as opposed to our present-day context. How do you go about framing a person’s truth, or truths?

Brereton noted of the three new biographies, author Aiyejina was fortunate in having a subject very much alive – Earl Lovelace – so interviews were possible. Raymond’s subject, McBurnie, died relatively recently, in 2000, so Raymond was able to interview her back then, and others who worked with her and knew her well.

None of this was possible for Cudjoe’s subject, Burnley, who died in 1850, and so Cudjoe had to rely on extensive historical research from documentary sources. Aiyejina said a main challenge for him was negotiating boundaries of close friendship with Lovelace to make judgment calls on personal qualities to write about – he did this tactfully, only including personal matter that illuminated Lovelace’s essence as a writer. Aiyejina also said having any kind of structured interview with Lovelace could be challenging – so he just let him talk, or be meditatively silent, and accumulated stacks of tapes from which he later distilled meanings. Deciphering Lovelace’s “crapaud-foot” handwriting was also an issue.

Raymond said she interviewed a cross-section of people to inform her book on Beryl McBurnie, as well as hunting through 35 boxes of water-damaged, worm-eaten old books and papers belonging to McBurnie and stored in the Heritage Library.

Raymond noted there were definite advantages to writing about someone dead, because a live person can have a vision of themselves or the meaning of their work that does not match how a biographer sees them or how other people see them – which can lead to a subject strongly objecting to what others write about them.

Cudjoe said crafting a biography about Burnley presented problems of researching material from many sources. He did lots of literary archaeology, digging broadly and deeply into UK archives, before shaping what he found with academic, intuitive and artistic skills to plot a non-fiction story.

Brereton asked: Does a biographer have to like or admire his subject? Cudjoe responded that for him, the question is irrelevant: the subject of slave-owner Burnley is important in a geographical, historical and intellectual sense. He said to understand slavery, one has to understand the roles of both the enslaved and the slavemasters, and that of all the Caribbean islands, Trinidad is the only place with absolutely no biographies or histories of slavemasters. The implication was that we cannot choose to ignore what we do not like.

Raymond agreed with Cudjoe that one cannot only write about heroes or people one admires, but she admitted she personally found it difficult to write about someone without having personal feelings about the subject.

She also noted that any subject will have faults, and the challenge of good autobiography is honestly to portray a nuanced life in its achievements as well as its flaws. She also commented some of the region’s achievers have tried to pre-empt biographies by writing their own autobiographies which usually leave out the “difficult bits” – such as Eric Williams’ Inward Hunger, or PJ Patterson’s memoirs.

Aiyejina said for him, it’s not the subject matter that is important: it is what you choose to say about it. “So you can write about the devil…It is what you say about the devil that I want to know.”

Earl Lovelace

The history of British colonialism and its negative legacies of racist, economic, spiritual and cultural oppression are triggers for the creative works of another writer, Earl Lovelace. Retired UWI literature professor Funso Aiyejina’s biography of him, published in August 2017 by UWI Press, explores the life of this award-winning Trinidadian writer of evocative, lyrical fiction, short stories, plays and journalism.

Born in Toco in 1935, with his early childhood spent in Tobago and his teenage years in Belmont and Morvant in Port of Spain, Lovelace has always been rooted in Trinidad, never leaving to write abroad as many of his contemporaries did. He quickly left an early job as a proofreader for the Trinidad Guardian to work as a forest ranger in Valencia as a young man, and later worked as a visiting literature lecturer at several US universities and was a full-time lecturer at UWI St Augustine from 1977-87 while working on his creative writing.

Lovelace’s major works include the six novels While Gods are Falling, 1965; The Schoolmaster, 1968; The Dragon Can’t Dance, 1979; The Wine of Astonishment, 1983; Salt, 1997; and Is Just a Movie, 2011.

“The castaway, the alienated, the rebel and the underprivileged would be central to his fictive constructs,” notes Aiyejina in the new biography, which eloquently and concisely explores Lovelace’s learning curve as a writer and as a person increasingly concerned with reparative justice.

Beryl McBurnie

Raymond’s new book, Beryl McBurnie, published in 2018, is about the determined, vivacious, temperamental Afro-Trinidadian dancer Beryl McBurnie (1913-2000) who founded the Little Carib Theatre and who revived African-inspired folk-dance culture in Trinidad. McBurnie was part of an anti-colonial movement that recognised the value of Caribbean culture in a context of widespread colonial snobbery and prejudice against indigenous (non-white, non-European) cultural forms in the region. The book Beryl McBurnie is part of the Caribbean Biography Series from the UWI Press.

McBurnie was a charismatic woman with a vision of the value of folk dance as well as an appreciation for many other TT folk forms such as local theatre, Orisha-influenced drumming, pan music and Carnival arts and crafts, and Raymond has written that it was McBurnie’s passionate example which helped motivate Jamaican scholar, social critic, choreographer and UWI Vice Chancellor Rex Nettleford (1933-2010) as a younger man in 1962 to form the world-class Jamaica National Dance Theatre Company, which continues proudly to this day. Sadly, McBurnie never achieved similar success in her own country, but the biography succeeds in evoking a complex, idiosyncratic and fascinating life.

William Burnley

Cudjoe’s new work, The Slave Master of Trinidad, published 2018 by University of Massachusetts Press, looks at the life of British businessman William Hardin Burnley (1780-1850), who was the richest, most influential landowner and owner of enslaved Africans in Trinidad during the 1800s. Born in the United States to English parents, Burnley settled in Trinidad in 1802 and stayed here until his death in 1850.

Thanks to a combination of his race, education, wealth, social connections and business ambitions, Burnley grew to become a major power player, businessman and societal influencer in colonial Trinidad, moving fluidly through the Atlantic world of the Caribbean, the US, Britain, and Europe to advance his business and personal interests. Among his friends were Alexis de Tocqueville, British politician Joseph Hume and British prime minister William Gladstone. Burnley often butted heads with colonial governors in Trinidad, whom he regarded as transient functionaries.

He built himself a mansion at Orange Grove Savannah to rival any British governor’s official residence.

Burnley was a spokesman for the planter class and vehemently opposed the abolition of slavery, preferring to profit from the forced labour of Africans and their complete subjugation in the plantation system, and advancing racist reasons to justify this.

Cudjoe has reported that when enslaved Africans were emancipated in 1834, Burnley alone received something like £40,000, which constituted most of the compensation that was paid to Trinidad planters at the time.

Comments

"Heroes and Villains"