The sea is poetry

"It’s the surprise of poetry that I’ve been all over. It makes you a traveller.” ---Ishion Hutchinson

FIRST, HE writes it all out on a yellow legal pad. The language flows, pages and pages. He works on a red wooden desk made from a repurposed door. He sits daily at this desk, up early in the mornings at 6 am, watching light rise over buildings in the distance.

He’s not in Jamaica any more. This is Salt Lake City, Utah, a place where there is no water, no sea.

Instead, he creates an ocean for himself, right there on the page, his images cascading, taking orbital motion, swashing, breaking, foaming, releasing ideas as a wave throws up flotsam.

He writes draft after draft, fluidly, over weeks, then types it all up, prints it all out. By the tenth iteration he senses he might be a little closer. He cuts, cuts, cuts. More cuts, themes are condensed, strands taken up. Until, years after he begins, he arrives at a pace that matches his intuition about what this poem should be.

“I needed velocity,” says award-winning poet Ishion Hutchinson, “velocity that could be so rapid as if it were mad brush strokes on a canvas in which the narrative is only within the strokes, the story crystallised to the point where it does not stand any more and all that is left is the speed of it.”

The resulting poem tells us about him.

“At nights birds hammered my unborn,” it begins. It continues, over the course of 14 lines that move with the velocity of water, into a stunning transformation. “I smashed my head against a lightbulb / and light sprinkled my hair; I rejoiced, a poui / tree hit by the sun in the room, a man, a man.”

This becomes the centre of House of Lords and Commons, a poetry collection that conjures, through words, the turbulence, erosion, motion of the sea.

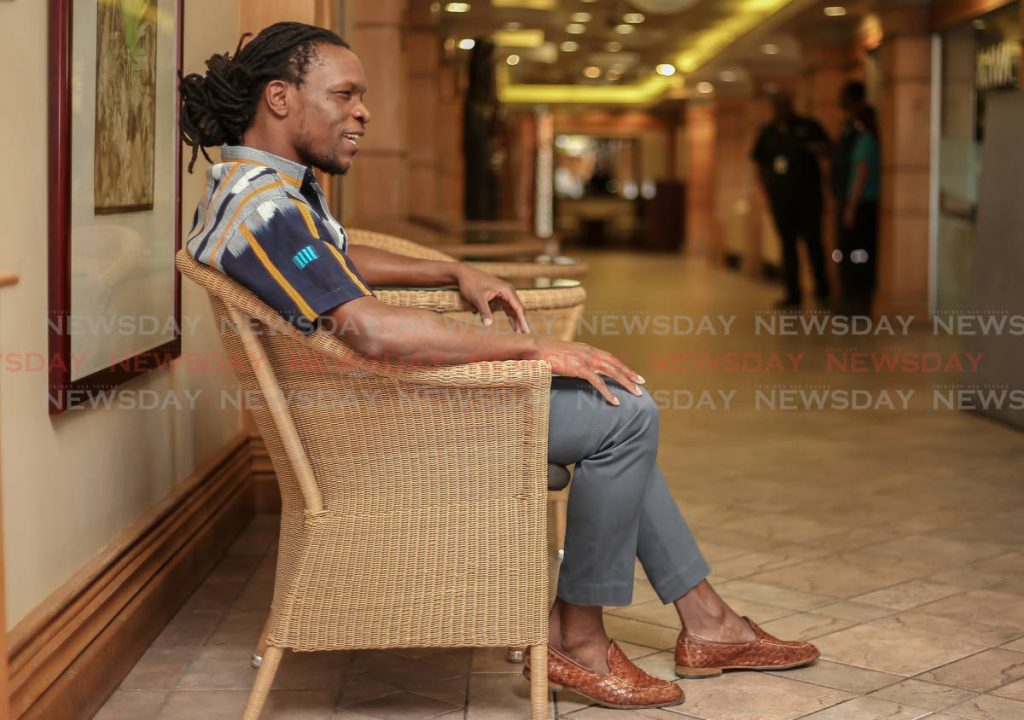

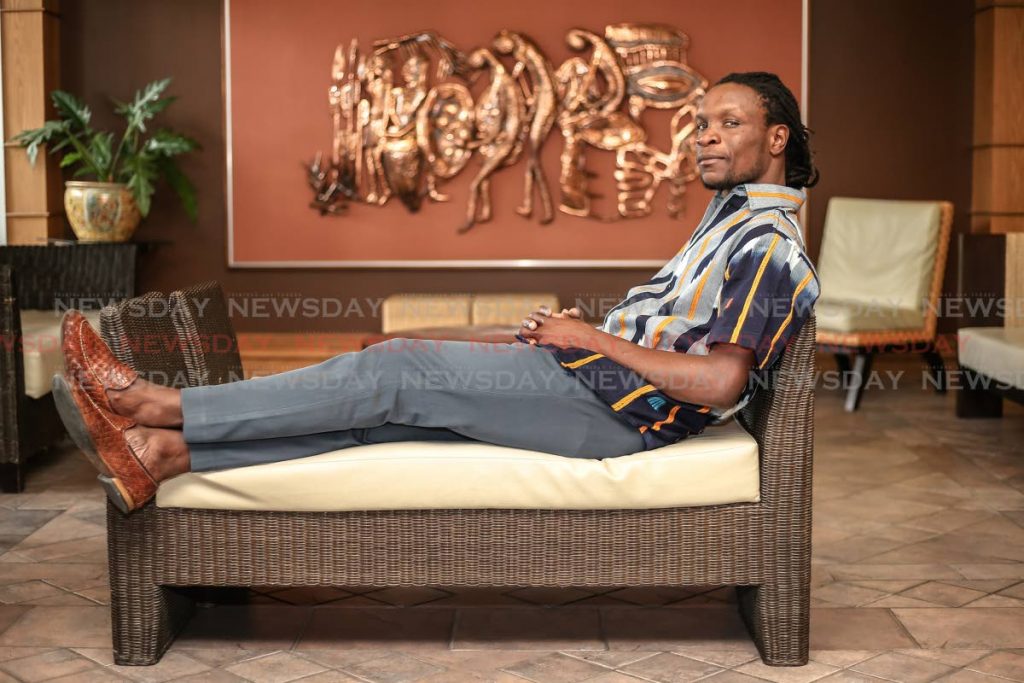

Hutchinson was in Port of Spain last week to take part in the inaugural Derek Walcott Festival, part of a series of events put on by the Walcott estate to commemorate the late Nobel laureate.

He sits in the lobby of the Kapok Hotel, at one time a haunt of Walcott’s, wearing a striped shirt from the Gold Coast. Just as his fashion crosses boundaries, so too does the poet. Since starting to write in Port Antonio, Jamaica, his poetry has taken him to places like Baltimore, New York, Rome, London, Berlin.

But his exploration of the world begins closer to home.

“Trinidad was the first place I ever travelled to when I was in my first year at UWI,” Hutchinson says. “I spent a summer in Tobago. It’s the surprise of poetry that I’ve been all over. It makes you a traveller.”

Yet no matter how far the journey he always returns to one place. “I was born in Port Antonio,” he says, “in a little town of the eastern section of Jamaica in a parish called Portland.”

His mother, Hermine, and father, Ira, were Rastafarians, and worked in the Port Antonio market. Poetry was not a word at the forefront of life, but the spear of language was. Hermine would set exercises in Hummingbird copybooks for her children.

“She would start a story and I would pick it up. I was eight years old at the time. My mother worked a lot with making things. She would crotchet and knit.”

More threads for his passion would be added when his father, Ira, moved to London.

“We wrote each other,” Hutchinson says. “This kind of communication was part of my young childhood. In one letter I was trying to figure out my own ambitions and I wrote that I wanted to be a journalist. The letters were weekly, from nine years old up to sixth form.” So whether in epistolary form or through discrete exercises, a feeling for narratives of becoming emerged.

Hutchinson’s close relationship with his grandmother May was also pivotal.

“She was a very quiet woman, very reserved. She always liked and preferred to be by herself. I clung to her.”

May was a baker, and Hutchinson came to live with her for extended periods.

“In my work there is the ghost of a place,” the poet says. “I always seem to be writing from the same place, which is specifically the landscape I grew up in, particularly my grandmother’s house, which is built on a hill in Port Antonio. This house overlooks the sea. In a sense my stirring into language was this specific place. This is the nucleus. Everything grows out of that.

“In front of this view the sea has a visual limit and seems as if something you could walk down to and arrive at.

“But in fact any kind of movement towards results in it moving away, becoming more distant. There is always this chase, as if I am lured to chase that image of the sea.”

Hutchinson might as well be describing the effect of his own poetry. Even when ostensibly addressing subjects that do not relate to the coast, such as Station or Anthropolog’ from his first book, Far District, his lines embody the ebb and flow, the multitudinous forces within the crest of a wave. Meaning and narrative are telegraphed and undermined, we surf and dive until we get a sense of the poet himself plumbing the depths, retrieving truth from the interstices of the complex wave play.

Little wonder Hutchinson has thus far received the US National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Whiting Writers Award, the PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award and the Larry Levis Prize from the Academy of American Poets. He was recently announced as a recipient of a Windham-Campbell Prize, alongside figures such as Kwame Dawes and David Chariandy.

All of it has allowed Hutchinson to deepen his love of language. West Ride Out – a more recent poem published in the Autumn 2017 issue of The Poetry Review – shows a writer committing even more unequivocally to a radical embrace of prose within the framework of flowing lyricism, turning back to John Donne yet moving forward into a line that is as sensual as it is broken: “And love grows angel in the gloam,” it begins, “with your calls through resistant stars.” In his language, the poet seems ever nearer to transforming, at last, into seawater.

Comments

"The sea is poetry"