The roots of dragon mas

SHEREEN ALI

DRAGONS stomped on the road, slithered like lizards and raged in fury at the chains binding them; some dragons even blasted real fire and smoke from their mouths in the Trinidad dragon mas of long ago.

TT dragon mas was the focus of a talk on March 12 at Castle Killarney (Stollmeyer's Castle), Maraval Road, Port of Spain, where three arts veterans shared thoughts on the roots of indigenous dragon masquerades. Leading the talks were craftsman and mas player Larry Richardson; arts manager Ronnie Joseph, and painter Ken Crichlow, the founding lecturer of the Visual Arts Programme of The UWI’s Department of Creative and Festival Arts.

A small, attentive audience of about 40 people learned that a man called “Chinee Patrick” – Patrick Jones (1876-1965) – brought the very first dragon mas to Trinidad Carnival after seeing a picture of Inferno (Hell) inspired by Dante Alighieri’s 14th-century epic poem The Divine Comedy, about the journey of the soul through nine circles of hell. Jones was a voracious reader.

“Chinee Patrick” was quite an inventive character: the Trinidadian son of a Chinese shopkeeper father and a Euro-African mother, he was a pyrotechnician, an anti-colonialist, a storyteller, and a calypsonian, in addition to being a Carnival bandleader. Carnival Institute director Dr Kim Johnson commented that Jones probably drew on his Chinese heritage in introducing more ornate costume qualities to an earlier tradition of “dirty” devil mas practised in rural Trinidad.

Johnson also commented on the influences of an African ethos in the way Jones’s devils operated. Their devils and jabs were not so much intrinsically evil or anti-God, but rather, they were reinterpreting the Christian concept of the devil in their own terms: devils were doing God’s work by punishing sinners and keeping you on the right path. “So it’s a peculiar combination of the Chinese, the European and the African, which to me symbolises the Carnival,” he said.

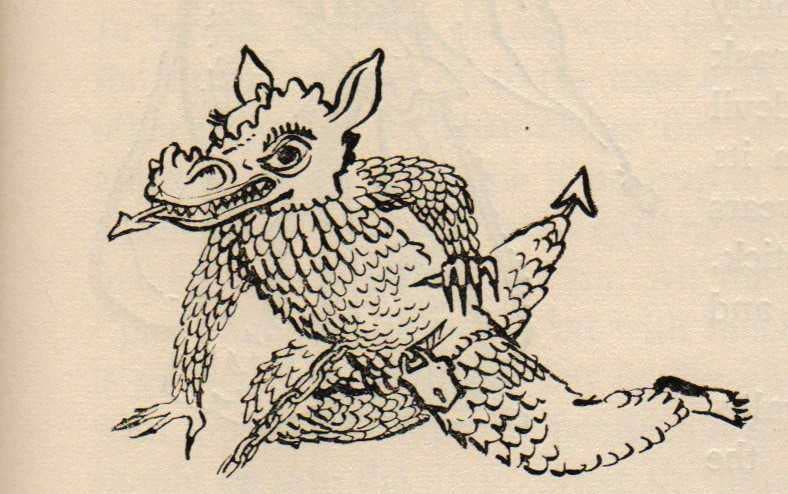

Historian Gerard Besson says in his blog archives that Chinee Patrick brought out his first dragon mas bands from 1906-1908, using cow horns, rope tails, and flexible flapping wings. In 1910, Jones brought out a band called Demonites, featuring Beelzebub, Lord of the Flies, enclosed in an iron cage and bound by nine chains, carried aloft on poles. In 1911 Satan joined the party, along with a book and a pen to record sins. In that year too, the Beast character first appeared in a costume made of remarkable moveable fish scales. Every year, Jones’s band would build the Dragon’s head in greatest secrecy to better astound spectators.

Patrick Jones introduced a fresh approach to craft making using simple materials like papier maché, bamboo and recycled matter to build a medley of tails, fins, scales and reptilian wings sprouting from all manner of imps, devils and beasts.

The University of the West Indies, UWI Department of Creative and

Festival Arts; and Larry Richardson, veteran masman, costume

fabricator and a player.

Artist Crichlow explained that traditional dragon mas grew out of devil or jab jab mas in the years before World War II. This was a time long before mobile steelbands, before streets became clogged with masses of people partying, and before calypso became the accepted music of Carnival. The devil/dragon bands were humble neighbourhood groups who invented their own arts, crafts and playful street dramas to be performed at their leisure, often just within a few blocks of their home communities in Port of Spain. Despite sometimes very limited resources, they improvised and still found ways to make costumes and have fun with them.

There were special conventions associated with these early dragon bands. Sometimes, a King Beast might take half an hour in dramatics just to leave his front door and reach the pavement: and he’d have to leave his house walking backwards! Indeed, each character would have to do his own special ritual to get out of his house just in order to join the band.

From just a handful of initial costumes, later dragon bands evolved a whole hierarchy of sometimes comedic, sometimes grotesque devils, imps, beasts, and female temptresses, with very specific roles to perform. The King Imp, for example, would ring the bell and blow the horn, signalling the start of the mas. The Axe Imp would clear the way for the band. The Key Imp would brandish a huge key to release the caged Beast and unlock the padlocks binding the chained dragon. The dragon or beast guarded the gates of Hell, which, when opened, would release a horde of imps and jabs to taunt, tempt and test the citizenry.

Meanwhile, the Imp of Justice would hold a set of scales to weigh your sins and pass this information on to Satan, so that Satan could put you in exactly the right place in Hell for you. Part of a traditional dragon mas involved theatrics around crossing water – whether water as symbolic holy water repugnant to evil spirits, water as a feared mirror of the soul, or water as a reference to the River Styx, which in Greek mythology was the river the souls of the newly dead had to cross to get to the Underworld.

In Trinidad mas myth-making, the river or water became the street-side canal, before which beasts and dragons would pause and enact complex anguished antics and acrobatics before being able to cross over them.

Some devils enacted their disturbance at seeing their own terrible reflections in water; others, it is said, were afraid of having no reflections at all. Canals or bridges were symbolic but also very physical impediments to progress, over which players had to improvise varied ways of dancing, leaping or skittering to advance.

“Duncan Street. Nelson Street. George Street. Queen Street. St James. Newtown. San Juan….and San Fernando. There is a difference in the makeup of the streets that really affected the dragon band,” said Joseph. “The dragon band needed canals, so that Duncan, Nelson, George Streets and so on were ideal.”

Larry Richardson reflected on the barrack-yard style of gritty working-class life influencing the mas. “I can vaguely remember stories that my grandmother told me: ‘Yuh grandfather used to lime in Lai Lai yard… the DNA has always been something of curiosity as to how these communities survived, how they provided entertainment for one another…What was the expense?...Was it an unconscious desire to become more than just where you worked, who you worked for, and who you limed with?”

In Trinidad dragon mas, influences were diverse. They ranged from the mediaeval Christian legend of St George slaying the dragon, in which dragons were seen as monstrous, evil destroyers of sanctified order, to the distant echoes of Chinese dragons, who were symbols of power, wisdom and supernatural strength.

Some early Trinidad dragon masquerades used the dragon as an aerial costume to be manipulated on poles above the head. Other dragon mas portrayals integrated the costume on to the body, with movable jaws in a papier maché head, glittering colourful strips of scales on a bodysuit, mobile tails, mandatory oversized claws, and small to moderately-sized wings which did not impede the need for the mas player to wriggle and writhe on the ground and enact the drama of an enraged, disturbed creature retreating and attacking, struggling to get free.

Some other dragon costumes sported seven heads, referencing the Sevenheaded Beast in the biblical Revelations of St John. There were caged king beasts, chained monster beasts, and free roving stray beasts and baby beasts.

The audience learned that back then, a person could not decide, just so, to play a King Beast on a Carnival Tuesday: you had to train for the part, and wait for the existing lead player of that role in the band either to die or to stop playing this mas character, before you could be considered worthy of inheriting the part. You had to earn that privilege.

There was always a huge class divide between downtown mas (lower-middle and working-class people) and uptown Savannah mas (wealthier citizens), the talkers reminded the audience. And most of the creative traditional mas forms, including the dragon bands, came from downtown.

Richardson paid respects to the extraordinary masman Narie Aproo, who both built costumes and played many commanding traditional mas portrayals, including imps, dragons, midnight robbers, Black Indians and many others. Said Richardson: “Narie is the authority on the dragon band…His father would have been in the original Dragon bands by Chinee Patrick.”

Later, Richardson commented: “That whole process of (performing) the dragon band is the most intriguing thing…How much of the unconscious it is about, and how much it is about a common unconscious that needed to be expressed at that time in our history, about who was good and who was bad, who was evil and who was sad?

He added: “I think in our collective unconscious, we may be kinda coming through a similar phase at the moment, where good and evil again find themselves being played out on the streets at Carnival time.”

This dragon mas conversation was part of Carnival at the Castle, a multimedia exhibition presented by the castle in collaboration with the Carnival Institute and the National Archives.

The exhibition runs until March 30, Monday-Friday, 10 am-6 pm and Saturday, 10 am-2 pm. Admission is free for all events.

For group visits, contact castlekillarneytt@gmail.com or 358-5755.

Comments

"The roots of dragon mas"