Mas divinity

SHEREEN ALI continues her exploration of spirituality in Carnival.

Trinidad Carnival has seen spiritual and religious influences of many different kinds in its music and in its masquerade designs and performances.

To take an example from the life of just one man, the calypsonian Garfield Blackman (Lord Shorty, later Ras Shorty I, 1941-2000) made a conscious shift away from the feelgood party music of his youth, after a period of deep soul-searching following some serious challenges in his life.

After an early life of carousing, drugs and singing risque calypsoes in the 1960s and early 70s, the former “sagaboy,” who is said to have fathered 23 children, found religion in the 1970s. During the 70s he was also experimenting with mixing African-influenced folk calypso forms with aspects of Indian music to help create the early sounds of soca (“soul of calypso”). His soca song Shanti Om, released on the 1978 album Soca Explosion, was a big hit of Carnival 1979 . Shanti Om borrowed from an Indian meditation mantra to make a cross-cultural appeal for peace and unity, using a blend of TT musical and spiritual influences.

By 1980 Blackman and his family had left city life for the Piparo forest. Blackman committed to changing his own life for the better, and proceeded to do just that. He adopted a strong Christian spiritual path to guide himself and his family. In Piparo, Blackman started composing a different kind of music with inspirational or cautionary messages, and formed a family band called The Love Circle, whose gifted musical members have gone on to varied musical careers.

By the late 1980s, the talented Blackman was mixing soca with Christian gospel influences in a style he called Jamoo (Jehovah’s music), writing hits such as the moving 1989 Watch out My Children, about the dangers of drug abuse. That song touched many people’s hearts, and in 2002, it was chosen as the theme song for the UN International Drug Control programme.

In a 2004 edition of Caribbean Beat, Georgia Popplewell wrote: “The definition of jamoo as gospel-soca didn’t begin to describe the nuances of this roots music, which incorporated elements of folk, reggae, jazz, and rock, and had plenty in common with the work of artists like Andre Tanker and the members of the rapso movement.” So in Jamoo music, we see Christian beliefs influencing soca music, which in turn branched out to embrace many other sounds, changing itself yet again in a process of cultural discovery and connection.

Orisha/Spiritual Baptist culture and Carnival music

The very sounds, music and expressive forms of some of our earliest traditional calypsoes owe a debt to West African Orisha religious traditions, says American anthropologist Frances Henry. She notes that in both the Orisha and Spiritual Baptist faiths, there are African traditions of rhythmic percussive music centred on drumming, call-and-response singing, and the use of the voice as an instrument – “doption” – as well as the use of movement and dancing (jumping and shaking, for example.) Spiritual messages and expressions happen through the body, not through preaching, and Orisha prayers are sung rather than spoken, so that the music is integral to the bodily forms of worship.

All these qualities – the use of the body, dancing, drumming, “doption” and call-and-response singing – helped shape calypso music, says Henry. She cites Raymond Quevedo (Atilla the Hun) as saying that some “kalinda” songs that became part of early calypsoes shared the same tempo and rhythm as Orisha religious chants.

Calypsonian David Rudder has drawn on many secular as well as spiritual influences, including Catholic, Anglican, and Shango/Orisha/Spiritual Baptist influences, to give life and add meaning to his rhythms and his songwriting.

Interviewed by Henry for her 2003 book Reclaiming African Religions in Trinidad,

The Socio-Political Legitimation of the Orisha and Spiritual Baptist Faiths, Rudder told her: “Basically all the things you hear in my music right now are the things I experienced as a child. These things manifest themselves now.

“In Belmont where I grew up I was surrounded by so many different influences, we had steelband yards, two of them, right on the road was a Catholic church and an Anglican church. On the hill just above where I lived, there was a Shango yard, and up the Valley Road, a couple of blocks from me was the Arada (Rada) Yard which was actually the first settlement in Belmont Valley Road, with Papa Nani, so that is how I got locked into these influences, really. When I create, they just tend to manifest, because I go back into where I came from and these things reveal themselves.”

Spiritual influences in the mas

In Carnival masquerade arts, crafts and street performances, there have also been many crossovers between the spiritual or sacred and the more secular, flamboyant aspects of street parades, if you choose to notice them. The influences can be subtle, indirect and disguised, or in the explicit use of religious themes in mas.

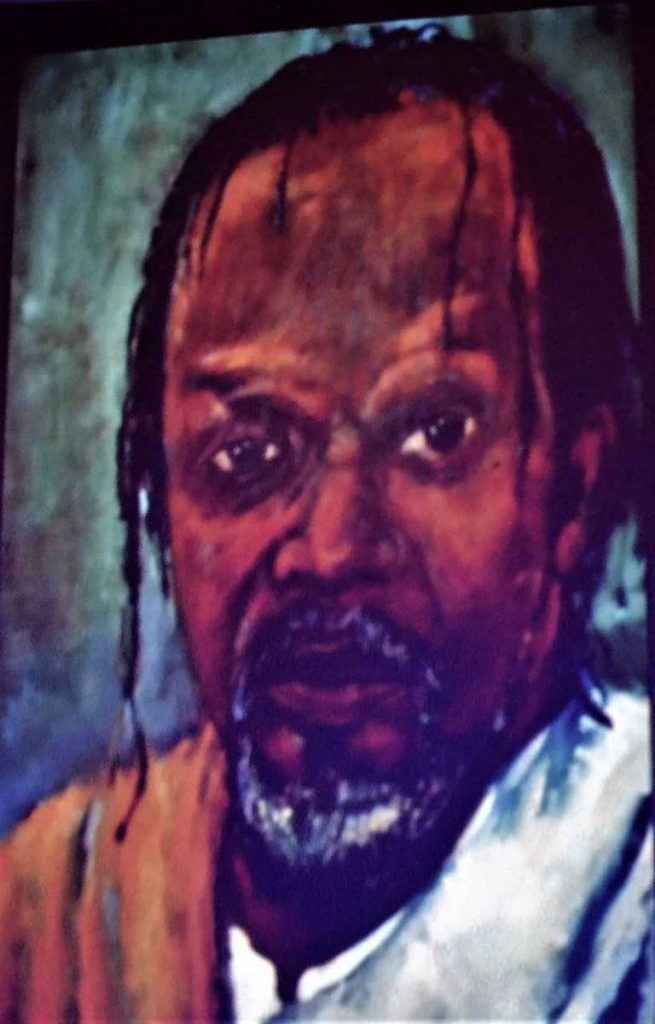

The work of artist and masman Peter Minshall is one example. Minshall has long believed the mas has the potential to make powerful social, artistic and spiritual statements. Minshall’s 1976 designs for the Stephen Lee Heung band Paradise Lost took as their starting point the epic poem by John Milton about the biblical story of the Fall of Man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

Minshall designed Paradise Lost in four epic movements: Pandemonium, the Garden of Eden, Paradise, and Sin & Death. Dozens of snarling hellhounds opened the mas; a morality tale of high drama, spectacle and artistry followed, including Fallen Angels, a burning lake, and a near-naked Adam dancing with a gleaming red apple in one hand and a serpent’s head in the other.

TT people had never seen anything quite like it on a Carnival road before: Minshall made his mas theatrical and into a form of participatory performance art with great emotive power beyond mere partying. In his subsequent artistic career spanning more than three decades, he has conceived many other inspirational mas productions and individual costumes that touched on matters spiritual or ethical, including his moving trilogy of good versus evil in the River (1983), Callaloo (1984) and The Golden Calabash (1985); and the praise-song trilogy of Hallelujah (1995), Song of the Earth (1996) and Tapestry (1997).

From another tradition, the West African Yoruba masquerades, there are other spiritual influences in our Carnival. Egungun refers to Yoruba masquerades connected to ancestor reverence. Egungun layered costumes and strips of cloth in rich fabrics and colours completely hide the masquerader in arresting designs; when he twirls, the strips fly, creating a “breeze of blessings.” Through drumming and dance, Egungun performers would become possessed by the spirits of the ancestors, spiritually cleansing the community, and giving messages, warnings and blessings. The memories of Yoruba, Akan or other African religious masquerades may be seen filtering down into Caribbean portrayals of pierrot grenade (Trinidad), pitchy patchy (Bahamas and Jamaica Jonkanu) and shaggy bear (Barbados Tuk bands).

This year, spiritual influences in the Trinidad mas bubbled up in two poignant 2019 portrayals, the Band of the Year winner, K2K, and the Mini Band winner, Moko Sõmõkow. Though quite different in scale and symbolism, both bands touched on ideas of spiritual transformation.

Christian church and moko jumbies

The band K2K, led by Kathy and Karen Norman, embraced the theme Through Stained Glass Windows, fusing high fashion and mobile-ribbed structural designs (including butterfly motifs) with the spiritual connotations of stained-glass windows in the fabrics. While stained glass can refer simply to the craft of making coloured glass objects, it is most intimately associated with the windows of Christian churches which since mediaeval times have used stained-glass windows as a major pictorial form to illustrate Bible stories and inspire worshippers through illuminated art.

K2K used the stained-glass idea as both a fabric design and a theme, unifying the entire band in a way that drew on ideas of spiritual transformation to inform how we piece together our selves and our lives: “Our lives are like stained-glass windows because they comprise...a juxtaposition of happenings that are soldered to memory. However, it is through the placement of those pieces that we discover the story of love conquering hate; a story of light piercing through the darkness; a story of hope dominating despair. Indeed our lives are a painted story: painted in colours so dark that they block out the light; painted in colours so vibrant that it lets the light in; painted spectacularly.”

Meanwhile, the small moko jumbie band Moko Sõmõkow expressed the metaphysical through diverse symbolisms and cultural influences suggested by Wilson Harris’s 1960 novel Palace of the Peacock. That story, about a group of multiracial men on a journey upriver in the Guyanese jungle to exploit indigenous people, becomes an almost hallucinatory exploration of liminal states between life and death, reality and unreality, Caribbean historical brutalities and strange moments of consciousness and transformation.

Moko Sõmõkow’s portrayal of Mariella, Shadow of Consciousness, played by Shynel Brizan, won the 2019 Queen of Carnival award this year. Artistic designer for the band is Alan Vaughan, whose mas designs since 2012 have consistently reached for sometimes intangible spiritual meanings through subtle symbolism and the sweeping flow of fabrics like sails or wings on the arms of stilt-walkers.

For Vaughan, the very form of a moko jumbie is especially meaningful. He says: “The sticks become as an altar – linking the earth and a spiritual force surrounding us like air in the sky. It is through the ritual robing of mas that we let the power enter us – and, certainly for me, it is an embracing, eclectic, ever-evolving force which is open to mark and celebrate the pain and joy of life.”

* Shereen Ali's first article Carnival: Sacred or Profane? was published on March 3.

Comments

"Mas divinity"