Power of statistics

The biggest challenge the Central Statistical Office (CSO) faces its lack of legislative clout.

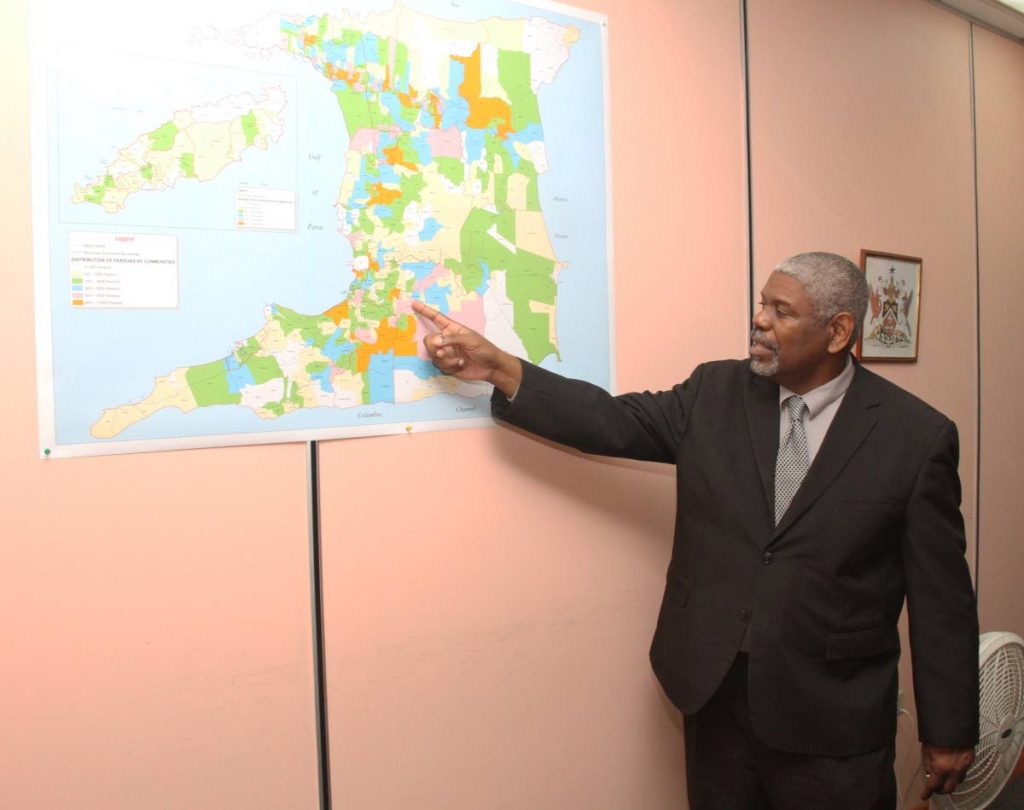

“The major constraint – the overarching constraint – is the legislative handcuff that the CSO is in. We have a mandate but we aren’t legally or legislatively empowered to fulfil that mandate,” Sean O’Brien, the director of statistics, told Business Day.

In a perfect world, along with collecting, compiling and publishing timely and relevant official statistics, the CSO as a national statistical office (NSO), would also be able to co-ordinate and train people throughout the national statistical system (NSS).

Instead, as it stands, governed by legislation that hasn’t really been updated since 1982, it can barely insist that it’s provided with data from other public bodies, much less insist that the data is formatted according to international standards.

It’s why, as far as O’Brien is concerned, the National Statistical Institute of TT (NSITT) can’t come fast enough.

“The NSITT would have the legislative potency that the CSO doesn’t have. It will have the mandate of coordinating the NSS. This is weakly stated in the current act but it is expressly stated in the new NSITT Act. That will lead to a lot more cohesion in NSS,” he said.

The act will also update key aspects of the organisational structure of the CSO, much of which hasn’t been updated since the 1960s.

This would include a modern human resource architecture, including provisions for positions like demographers, a web master or a web administrator, even an IT department.

“We don’t have an IT department. We have an electronic data processing department. So, while we have modern equipment, we don’t currently have the (facility) to pay for those positions because they are not part of the organisational chart. That’s why we need this transition. It’s not because the staff of the CSO isn’t any good, or we need new staff at the NSITT. It’s because the conditions the CSO operate under are not able to respond to new challenges,” he said.

The website, for example, is staffed by people who should be on the help desk or some other job, but have to double up – without compensation – to become web administrators.

“What you see on the website, what you see us producing – it’s produced under a lot of pressure and it’s totally outlined in all the International Monetary Fund’s Article IV reports. They outline it, though the media interpret those cries for help as the CSO being not good,” he said.

In the past, there have been superficial solutions, including moving to a more modern building with more modern equipment, but, O’Brien stressed, that was not the core problem. “People would wonder what’s wrong with us, but now that it’s finally being addressed in the NSITT, people, including the international ratings agencies, are starting to understand,” he said.

Among the challenges that will finally be able to be mitigated in some way, is access to information. The CSO relies on other agencies to give them data, but even though it can request that data, it can’t insist that it’s shared. Value added tax (VAT) data, for example, can’t be legally shared, even if the VAT office wants to cooperate. Then there’s the way data is collated. The CSO stringently adheres to the UN Statistical Division. And most major categories of public data have regulations, most public offices don’t necessarily keep up with the standards. It then creates double work for the CSO to clean that data to make sure it meets standards.

“CSO statistics are official statistics, which goes beyond just ‘statistics prepared by an official.’ Some people complain about late data, but much of that data is census data, which is valid for ten years. It’s still good,” he said, adding that the last national census was in 2011, so that data is good until 2021, although the next census will be 2020. Then there’s the continuous sample survey of the population, from which labour force statistics come from, but can only move as fast as the population is willing to assist in providing data.

Other data, though, like health or education, come from government agencies.

"Typically, a lot of data that is not available from the CSO are not available to the CSO in the first place. If we can’t get the data from the source we can’t invent it. The CSO is peer reviewed by the international rating agencies every year, so you have to make sure your data are of the highest integrity,” O’Brien said.

And since the CSO can’t force agencies to hand over data or even mandate what the style should be, it causes extra work for them to review and clean that data.

“Access is part of the problem. We need VAT data to compile timely and accurate GDP data but legislative constraints prevent it. But there’s also the problem that international methods are not intuitive, so you can’t produce it in accordance to those standards unless you are trained. At present a lot of the national statistical system don’t even know they are part of the national statistical system,” he said.

In fairness to them, O’Brien said, statistics aren’t a core part of their product so they just share the data they would naturally generate.

“We have to take it from them and process it into the standards,” he said.

This creates extra work but also, raises queries that need to be examined. For example, when the system at customs changed in 2014, a coding problem resulted in export data showing that TT exported several hundred tonnes of sugar – a decade after the sugar industry was shut down. Sorting that out and fixing it took a year, he said.

Once the NSITT legislation finally gives state statisticians some power, over their commodity, there’s still one final hurdle to overcome – public support.

“We need the cooperation of the public. The data can’t improve without, even if we move to the NSITT. Without a change in the mind-set of the public and various stakeholders, any change in administration will be cosmetic because we need people to respond to the CSO,” he said.

Under the current act, refusal to take part in the CSO’s surveys can result in six months’ imprisonment or a $2,000 fine. “We don’t think you can get quality data by threatening the public so we don’t put forward that face. We try to beg, encourage, pour our hearts out but we do have some legislative bite behind us. We don’t want this to go to that extreme. What we want the public to understand is the data we collect will help the government – whichever government is in power – serve you better,” O’Brien said.

Comments

"Power of statistics"