Imbert defends PM's finance figures

Finance Minister Colm Imbert yesterday defended the Prime Minister’s facts and figures in last week’s report to the nation, clarifying, explaining and annotating for the media just where and when the data came from.

“There’s a lot of uniformed, inaccurate information in the system,” Imbert said, adding that in an effort to ensure that there’s better understanding of what’s happening in the economy, he would be hosting a media conference every two months, or so, to give regular updates.

The first figure Imbert tackled was the oil and gas tax revenue from 2014 to 2016, when the country, rode a $17 billion high, down to a $1 billion low.

These numbers, he clarified, were just tax revenues from oil and gas companies, as opposed to the total revenue from the energy sector, which were a high of $28 million in 2014, before plummeting to $8 million in 2016 as global commodity prices collapsed. “The document being quoted by certain opposition elements (who are) attempting to dispute the (Prime Minister’s) figures (are) quoting from the 2018 Review of the Economy – my document. And they want to say my review of the economy document disputes the Prime Minister’s figures, well that’s nonsense,” Imbert said.

If the Prime Minister had quoted the higher figures, he said, it might have even proved his point better, and the “old talk” might have stopped. What the Prime Minister quoted instead were just the tax figures.

Public debt contained

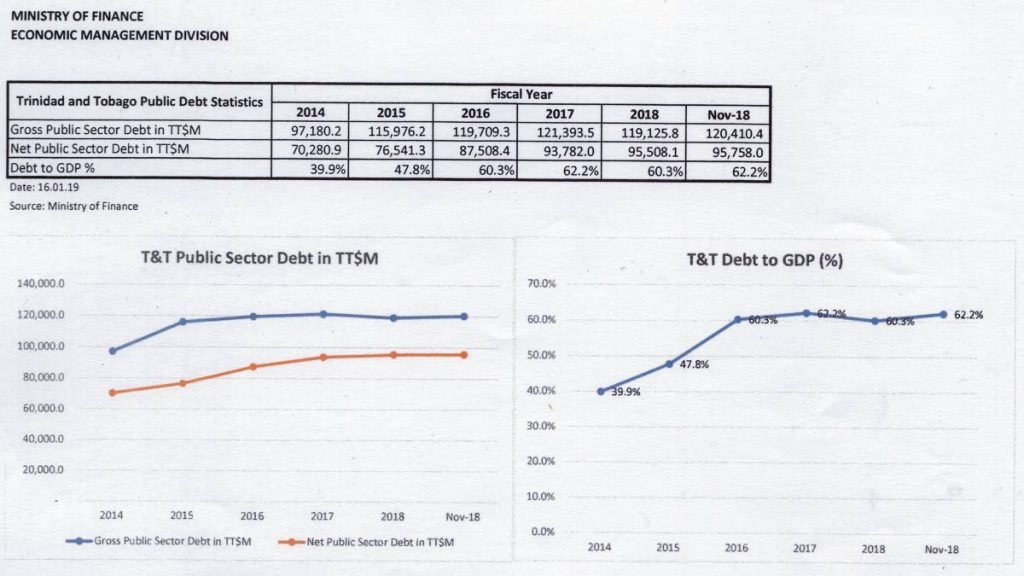

Next, Imbert clarified public debt. He started with a reference year of 2014, showing a steep increase in the net public debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio, which shows how much a country pays in debt in relation to how much wealth it creates. In 2014, the debt to GDP ratio was 40 per cent, but then spiked to 60.3 per cent in 2016 (which the Prime Minister had blamed on “election spending.”)

“We managed to contain it,” Imbert said, noting that while there was a slight increase in debt to 62.2 per cent in 2017, it dipped again in 2018 to 60.3 per cent again, and now it’s back up to 62.3 per cent. So we did quite well.”

The confusion arose when people used the gross public debt figures as an indicator, rather than the internationally accepted net debt figures. (Gross debt is the total amount of debt the government has issued, including debt owned by the government. Net public debt excludes debt owned by the government.) Even then, he said, the government had managed to stabilise the gross public debt.

“The net figure is what we actually owe. Debt to GDP more or less stable. So I think we’ve been managing debt quite well,” he said, dismissing his critics.

Regarding the government’s use of the overdraft facility at the Central Bank, Imbert said it was a good idea, because even though the government pays interest to the Central Bank (equivalent to the repo rate), at the end of the year, that interest is eventually returned anyway at the end of the year as revenue to the government in the form of profits from the Central Bank.

Imbert also defended the Prime Minister’s growth projection slide, which used combination of statistics from the International Monetary Fund and the Central Statistical Office. The IMF figures in particular had drawn much criticism, because the figure appeared much higher than the most recent country projection from the IMF in September 2018. Imbert said the government used the most recent figures from the IMF’s world economic update, and while he could not specify the date, he said at his next briefing he would provide the relevant data. The discrepancy, though, he said, was because of inaccurate data that had been provided, which is why the September figures were lower than the one used by the Prime Minister (0.9 per cent growth in 2019, compared to almost two per cent up to 2023).

Revenue back up

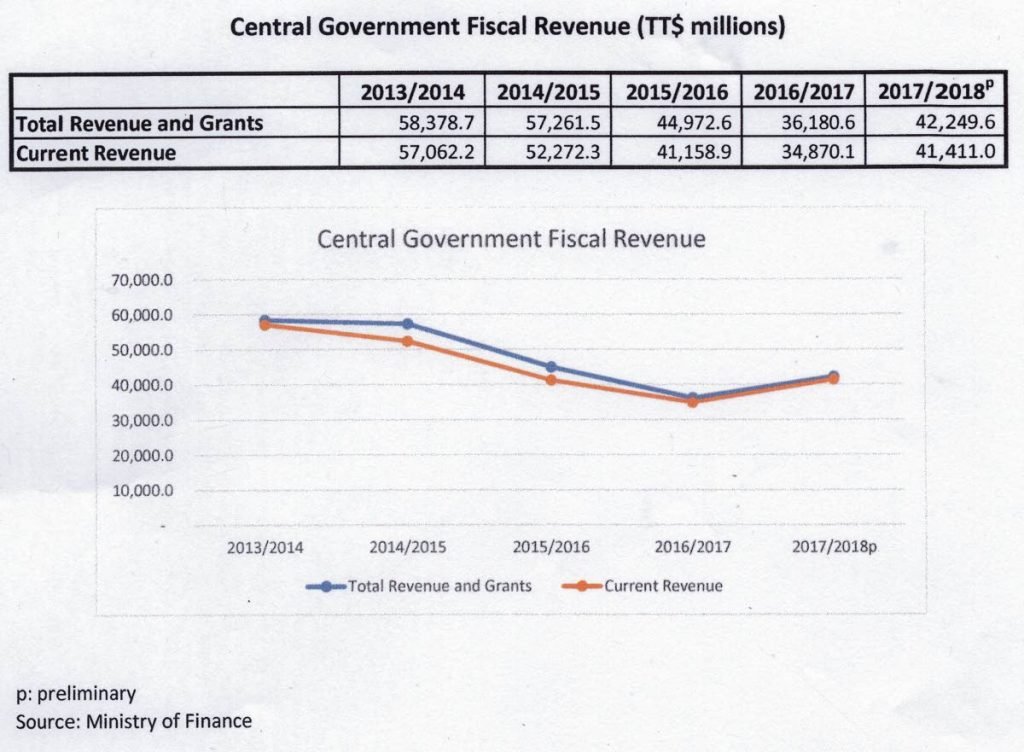

The most important figure Imbert pointed out was revenue which, when charted, he said showed clearly the turnaround he was talking about. There was a sharp drop in revenue, he said, from a high of $58 billion in 2014, to $36 billion in 2017. Now, it’s on the way back up, with $42.6 billion in 2018. “Now revenue is on the way back up. This is what I meant when I said the economy has turned around. Things are going back up. That’s what I meant that the economy has turned around. It actually has,” he said.

And for the first three months of fiscal 2019 (October to December), the country earned $11.3 billion, more than the estimated $9 billion to $10 billion. While Imbert admitted oil prices were lower, the country was buoyed by gas prices higher than the budgeted US$2.75/mmbtu. “When you balance the two we are meeting our targets,” he said. His outlook for the year, he added, was positive.

Comments

"Imbert defends PM’s finance figures"