Godfrey’s legacy

When some people receive an HIV-positive status, they think of it as a death sentence. But when Godfrey Sealy learned the news in 1988, he dedicated himself to improving the lives of the people of TT with HIV/Aids.

Sealy’s younger sister, Ann Marie Sealy, said her late brother, a playwright, director, actor, singer, producer, and HIV/Aids activist, contracted HIV while at school in Los Angeles. He got drunk at a party and slept with one man–and that was all it took for him to become infected.

After retuning home to tell his family the news, he visited his uncle, a professor at a university in Miami, to research the virus and see how best to deal with the situation. She said initially her 29-year-old brother was not interested in taking medication and instead focused on a more holistic lifestyle–eating right, controlling his stress levels, and living a better life.

Thankfully, he had the support of family, friends, neighbours, his theatre community, and even people on the street who simply knew of him.

“We were very close," she said. "Your family has to give you the love. It’s not just about clinical treatment as long as you have a great support system. I think that is what kept him for that period.”

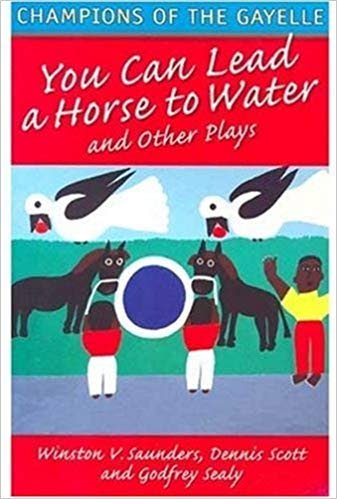

That year, Sealy staged his controversial play One of Our Sons Is Missing, the first in TT to address HIV. His sister said it was later adapted and became the focus of the Rural Aids project, a mobile Aids education programme staged in over 30 communities throughout the country, as well as in Jamaica, Barbados and St Martin. In 2005, a year before Sealy's death, the play was published by Macmillan in You Can Lead a Horse to Water and Other Plays.

After that he threw himself into activism.

Ann Marie said Sealy used his artform to educate and motivate people, but in a light-hearted way they would respond to, because he felt it was his responsibility as an artist. Because people loved and respected him, it was easy for him to find ways to encourage others to get tested.

“He became a teacher, mentor, brother, friend, companion, counsellor, facilitator to all who came into his life, and they were all welcomed with open arms. He worked with prostitutes, drag queens or female impersonators, bisexuals, the poor and downtrodden, people who were affected by some form of abuse, even vagrants.”

Educating people about HIV

Sealy worked on a number of community outreach projects and NGOs, gave motivational speeches, lessons in etiquette and discipline, and called for recognition of people’s rights. He did workshops at UWI, out of which came the idea for an HIV awareness production for primary school children, and co-founded CARE (Community Action Resource) with Bishop Clyde Harvey, then Fr Harvey.

“He took on the responsibility of organising medication, foodstuff and providing counselling for those infected and affected. For many years CARE was the only support group for persons living with the virus.”

In addition, she said he did several research studies on the gay community and in 2005 became a consultant with the Caribbean Regional Network of People Living with HIV/Aids (CRN+) on MSM (men who have sex with men) related issues. He also worked with several international agencies, including the Caribbean Epidemiology Centre, the UN Development Programme, the Pan American Health Organisation, and United Nations Aids.

“All of his work was educational. He wanted to educate people. He was blatantly honest. He wanted to motivate people. He wanted them to know there was still hope after being diagnosed with what was then a terminal disease.

"A lot of the programmes TT has now–meals, the medication, benefits, housing–he introduced or tried to implement. He really enhanced people’s lives on a national scale.”

Ann Marie said although those were times of discrimination and stigmatisation, Sealy’s status did not affect his career. In fact, his plays won seven Cacique Awards over his professional career. But, she said, as for any local artist, it was more productive for him to go abroad to work.

So in 2001, Sealy left to live and work in Miami and later London, where his work was highly appreciated.

“He was talented and had a passion for what he did. He used to help everybody. It was a gift that God gave him, and he truly had the passion for what he did. He gave people energy, had them pumping, and you felt that love. Everything he did, he did with love.”

However, while in London, Sealy decided he wanted to return home, because the city was too dreary for him and he loved TT. Ann Marie said by that stage, even though he was getting excellent medical care, he was confined to a wheelchair. As a social, friendly person, it helped heal him when he helped others, and so he returned home.

She recalled that his home at 33 Murray Street, Woodbrook, which was affectionately called Bohemia and is now the Big Black Box, was open to any and everyone.

“Having a brother like Godfrey was a fabulous experience. I learned so much about life."

So did other people, and he has not been forgotten. Even now, she said, "I meet a lot of people who ask me if we would not be staging any of his work. Funding is the main problem. but we are hoping that next year we can take a shot at it. with the assistance from a few corporate companies.”

Motivating a generation

Sealy was a mentor to many young people who wanted to get involved in sexual health and HIV/AIDS advocacy. One of these was Salorne Mc Donald, vice chairman of the National Aids Coordinating Committee.

“Godfrey Sealy was an icon. He was one of our first advocates who had gone through the gamut of getting on medication, but he literally gave his life for TT’s fight against HIV.”

He said Sealy told him he came out publicly as HIV-positive because one of the challenges in TT society was that people with the virus felt they had to hide, and they needed to see someone else do something before they would take action.

Sealy said if people kept hiding, the virus would be pushed underground, they would not have the support they needed to face their health issues, and no one would know when and how they died.

“He was one of the individuals that made connections regionally and internationally to understand how HIV was impacting various communities...He said someone had to be the first one on the ground and lead the charge. He said Normandy was not won by cowards hiding in the dark.”

Mc Donald added that Sealy did not have to return to TT, but he loved his country and came back to support and help with the fight. Sealy, he said, offered his home as a place to meet, carry out training, and hold dialogue. “He also offered it as a sanctuary to people who found that they were positive, who were cast out from their own homes.”

Sealy’s home was also a haven for the theatre community.

Actor, director and singer Wendell Manwarren of 3canal confirmed that Sealy opened his home for play rehearsals and practice, and others would come to lime and watch.

“It became a kind of community centre for people in theatre, which was now beginning to blossom – that commercial theatre outside of the established theatre workshops."

A fresh kind of theatre was taking place.

“Godfrey was fearless. He was very short in stature, but very big in personality. He was courageous and very sure of himself. He was committed to the idea that theatre performance was a viable career, and he was an example to those upcoming in the art.”

He said as members of the Tent Theatre, he and others received a lot of training from Sealy and his contemporaries such as Raymond Choo Kong, Ronald Guy James, Dwight Arthur and Mary-Ann Roberts.

Creating awareness through theatre

Manwarren described Sealy as a livewire, the life of the party, and a man who was not afraid to put himself on the line to deal publicly with what was a touchy subject in those days. His own first performance with Sealy was in 1990 as a pierrot grenade in the play, To Hell Wid Dat, when Godfrey used traditional Carnival characters to transmit safe sex messages.

“That show was then taken to Berlin at the World Aids Conference several years later. I believe Godfrey was a speaker at the conference, or had enough clout as a representative of this region to carry a contingent to the conference. I knew he was doing his advocacy on the ground here, but that’s when I realised how much of an advocate he really was.”

Manwarren said while he was not particularly involved in activism, people in theatre at the time were doing plays dealing with HIV/Aids and he was involved in that work.

“In the field we were working in, we were inherently involved, because it was life happening all around you. You were dealing with people on a real level, it was the living reality: you were losing friends and people you know. You couldn’t separate yourself from it, so you didn’t have to deal with it on an official level."

In addition to medical research, in the 1990s the virus was dealt with from a social perspective, with more and more plays and movies about it. Manwarren believed that marked a turning point as people learned how to protect themselves, change their behaviour, the different choices they had, and how to deal with the virus.

He lamented the lack of active education and awareness campaigns at present, however. He said it could not be assumed that people already knew about safe sex and would make the right choices, and believed the Caribbean would see a rise in new instances of HIV/Aids because of this lack.

He went on to compare HIV to lifestyle diseases: people were dying of diabetes, heart disease, and stroke which, most of the time, were due to their choices, but those people were not being stigmatised, even though their choices could result in their death, and their care came at a high cost to the State.

Just as people with lifestyle diseases were not discriminated against, he said, Sealy worked to ensure those with HIV were not treated with prejudice.

“He was a strong, clear voice advocating a message of awareness of the choices you make. He was way ahead of his time, because he was insistent that everybody had a space in society and a right to equal treatment, not to be discriminated against, that the State had a role to play in helping to tackle the epidemic at the time and fund medication.

"He certainly made an impact at the time.”

Comments

"Godfrey’s legacy"