Knowing the other side of the story

FROM as early as 1990, there are writings by Prof Selwyn Cudjoe about William Hardin Burnley. In the book Caribbean Women Writers: Essays From the First International Conference edited by Cudjoe, he wrote in the introduction:

“In 1823, William Hardin Burnley, the major slave owner in Trinidad who believed that ‘absolute power is the foundation of the Slavery, without which it cannot exist with advantage either to the governors or the governed,’

insisted that any legislative measure that was introduced to forbid the ‘flogging’ of female slaves would be detrimental to the well-being of slavery and slave family.”

It took Cudjoe ten years to complete the book The Slave Master of Trinidad: William Hardin Burnley and the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World, which tells Burnley’s life story and the role his life played in the evolution of TT.

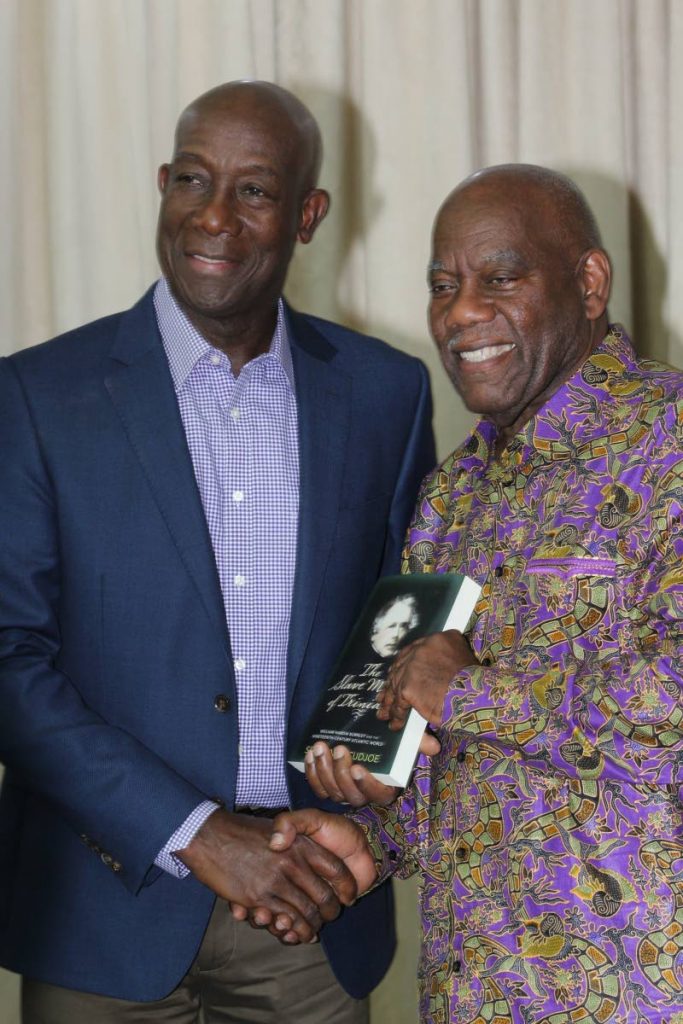

Cudjoe launched his book at the Central Bank on December 13. It prompted the Prime Minister Dr Keith Rowley to say, “This is solid, scholarly work which must find a place on the shelves of our schools. Not just for the children of slaves whom Burnley owned but for any person, man woman or child who would want to know about TT, the Caribbean, the diaspora.”

Similarly, Professor Emerita Bridget Brereton also recommended the book to everyone “with a serious interest in this nation’s history,” saying, “It is, in my professional judgment, a valuable and important contribution to the historiography of TT and by extension, the Caribbean. And I do sincerely congratulate him on its publication.”

Cudjoe also has some surprising personal connections with Burnley.

He said at the launch, “Burnley’s story is very much my story...it parallels my story. In 1830 my great grandfather was born in Tacarigua.”

He said in the 1905s, while growing up in Tacarigua, he knew a large, faded mansion in the Orange Grove Savannah that “had seen the last of its glories.” The mansion “stood there as a colossus on this magnificent expanse of land which, at that time, was one of the largest savannahs in the country second only to the Queen’s Park Savannah in Port of Spain.”

He was then a young boy and “could not have known that in this residence there once lived one of the most important men in the West Indies, during the first half of the 19th century.”

That man was William Hardin Burnley. The estate was a plantation that was central to the life of every person that lived in the district of Tacarigua.

“A century before or even 50 years before, there was several sugar estates in the area: El Dorado, Paradise, Laurel Hill, Macoya, etc. But by the 1950s, they all ceased to operate.

“Only Orange Grove remained as the central sugar estate in the area, around which all life turned. At crop time, that is from January to May, the entire village came to life. It was the source from which all the villagers received the necessary cash to buy items such as kerosene or clothing. Along with their meagre salaries they received from Orange Grove, they made ends meet by cultivating their provision gardens and tending their chickens, goats and cows,” Cudjoe said.

Cudjoe’s grandfather, uncle and even Cudjoe, himself worked at the estate during crop time. His family rented lands from the estate until the mid-1960s. That was when he began to become aware of Burnley’s immense significance.

“It was the late 1960s, when the Black Power (movement) and Marxist radicalism stepped in and I began to understand that William Hardin Burnley, the biggest slave owner in the country, was responsible for shaping much of the island’s policy between 1810 and 1815.”

Burnley, Brereton said, was born in New York in 1780, educated in the UK and came to TT in 1798, the year after Britain took Trinidad from Spain.

He became a permanent resident in 1802, Brereton added, and “had an immensely successful business career...He ended up owning many sugar estates, some he was outright owner, some he was part-owner or had partnership interest, including Orange Grove.”

She said at the time of Emancipation in 1834, Burnley owned around 1,500 human beings – enslaved people – and that made him the largest, single owner of enslaved people in TT “and one of the largest resident slave owners in the entire British Caribbean.” Burnley received the largest single share of the compensation handed out in the 1830s by the British Government to the former owners of human property in TT, Brereton said.

Some people, she said, might still be puzzled as to why Cudjoe had devoted so many years of his life researching the life of an owner of enslaved human beings, a defender of slavery and “an out -and-out racist.”

But historians, she said, “are trained to pay attention to individuals who are important actors and players in the movements of their time, not because they are admirable people, not because they are on the right side of history...but because they significantly impacted on the evolution of events and social developments in the time that they lived in.”

Dr Rowley said for him, the book represents the completion of the “education we need.”

“And I am sure all of you gathered here would want to read this, and I would like to believe when you read it, you too would feel that there was a space in your education...as certificated as we all are, there are huge gaps in our education which this book fills, not just as a history book but as a piece of ourselves. We will see ourselves in it.”

The society, Rowley said, needed to acknowledge and complete the record of its history by treating with the period of Burnley in a “more comprehensive way.”

The book, he said, answers “the question of who we are, where we came from and why we are so.”

A book like this did not exist among “the massive textbooks” that children read, he said, but perhaps it should. “And if it gets there I am confident that it will contribute to the development of the next generation.”

Comments

"Knowing the other side of the story"