Don’t cry for me, Olatunji

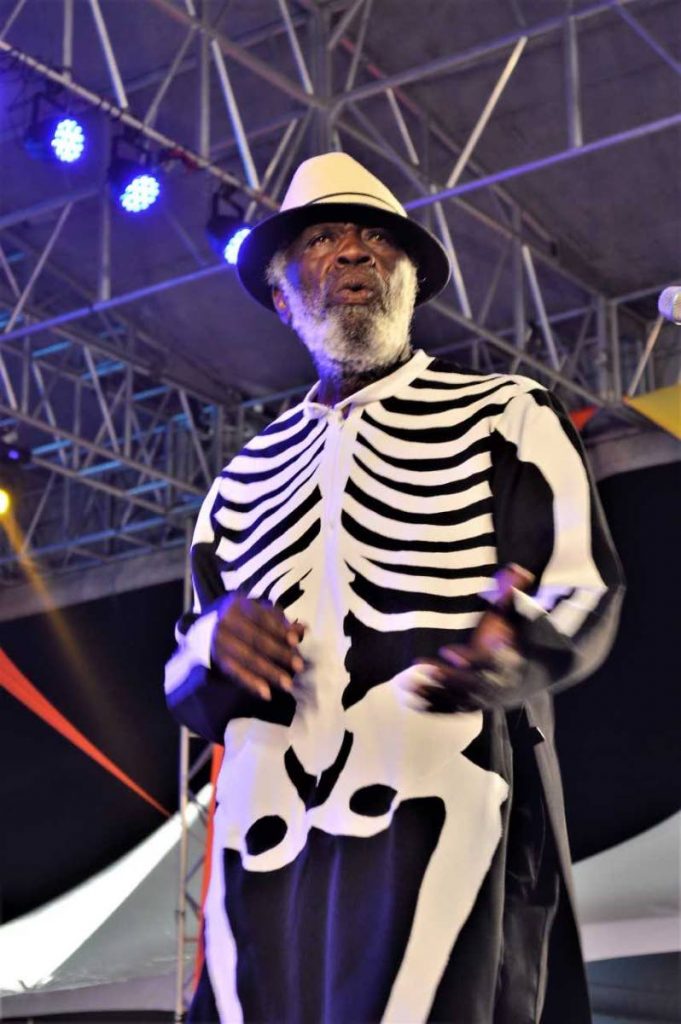

With homes and possessions swamped by clay-coloured water last weekend, Olatunji’s X Factor departure was the last thing on people’s minds. Days later, the death of Mighty Shadow threw Ola’s fate into perspective once more.

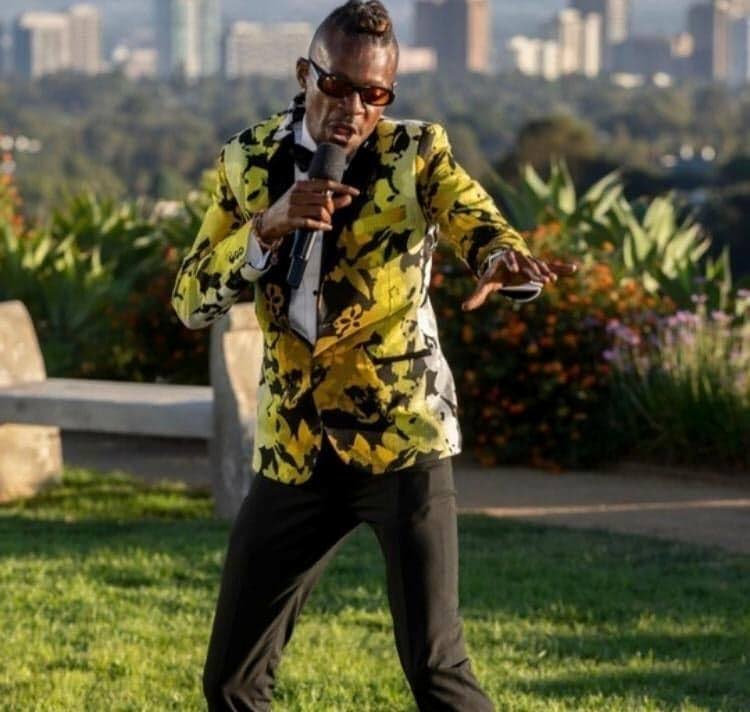

Shadow would never have entered X Factor and I wish Olatunji hadn’t either. I despise X Factor for the mortal wounds it has inflicted on the music industry. So, when I heard that former Soca Monarch Olatunji had entered the talent show I wasn’t gripped with excitement, as many were. I found it demeaning that an established artist should go among amateurs and perform for the approval of so-called judges.

To his credit, he performed some of his own material. But he also sang Mambo No 5, and that’s my biggest issue with X Factor: the karaoke element. Judging talent based on how well somebody can reproduce something. Often something cheesy, clichéd and done-to-death. Rewarding unoriginality.

Ola was never going to win X Factor because he’s not a pop star. And thank God he didn’t. As I told a friend who entered Miss World and should have won but lost, it’s a blessing in disguise. Opening doors and spotlighting TT internationally is one thing, but when you have to wear a crown for life that has no artistic merit that’s something you can’t shake.

Ola’s experiment does, however, open an important conversation about the artistic merits of soca in general. This week, a European expat told me that soca has no substance. He compared it to reggae and calypso, and the cultural, social and political importance of those genres, nationally, regionally and worldwide. As far back as the 60s, ska and reggae commented on Jamaican life in the same way calypso did in TT. I have long questioned why soca stars don’t use their platform to say something about social issues and promote peace – like Bob Marley, Ras Shorty I, David Rudder and Shadow did, and like Voice is now doing.

A counter narrative might be that soca’s strength lies in its apolitical nature. Like the acid house movement in Britain, the point of soca is to dance. Dance music allows us to forget about social problems. At a stretch, it challenges the prominence we place on societal issues, urging us to shrug off those bad vibes and think of other things. But what other things? Acid house was about euphoria, ecstasy pills and being transported to other worlds, even if you were in a tent in Crawley. Soca is, essentially, about rum and women’s bottoms. There is social rebellion in the pounding beats but none in the hackneyed words.

“Girl lemme see you wine up yuh bumper, and bring it closer to me,” was Olatunji’s opening line on his 2015 Soca Monarch-winning track. It wasn’t exactly Wordsworth, but it was infectious, groovy and effortlessly cool.

Shadow and his ilk were less concerned with the proximity of bottoms to groins and more with people’s lives. They were less interested in the influences of the blinged-up world outside Trinidad. But somehow, the preoccupations of calypso have boiled down in soca largely to those of sex and aesthetic materialism. It runs through today’s soca industry as it does in dancehall and rap. The masses don’t want to hear political comment when they’re trying to wine. That’s why calypso has become irrelevant to the younger generation. Arguably, Calypso Rose’s recent re-emergence, singing about the problems women face in TT, while wining and putting smiles on faces, proved, as Shadow did in the past, that entertainment and sending a message are not mutually exclusive.

X Factor isn’t concerned with messages, it’s concerned with outfits, hairstyles and marketability. Things that, while important, ought to be secondary to the music. Putting soca on the international map is important, as is pinning its origins firmly to the Trinidadian flag. As a foreigner I am acutely aware that, just like calypso and steelpan before it, the outside world sees soca as a generic Caribbean creation, not one forged here in TT and identifiably Trinidadian.

But selling your identity to a manufactured pop charade isn’t the way to market the genre.

Before his final X Factor performance, Ola sent thoughts and prayers to the flood victims back home. But where are the soca stars organising an impromptu benefit concert to raise funds for those who’ve lost everything?

Overseas, Nicki Minaj tweeted words of support for the victims. Let’s hope a nice fat cheque is in the post.

For those sleeping in shelters in La Horquetta or Warrenville right now, music may be the last thing on their minds, but if they are looking for a sign that someone out there understands their plight they probably won’t find it in tales of fetes and flowing drinks. Unless of course they are searching for escapism, which is when soca comes into its own.

Comments

"Don’t cry for me, Olatunji"