How do you grieve?

Tomorrow would have been my mum’s 63rd birthday. Her final birthday, her 60th, was spent in Paris. It was a surprise. We wandered down the Champs-Elysée and friends and family appeared before her eyes. She cried. She was happy. She was very ill. She still insisted on walking everywhere.

Three months later she died at home. I’ve lived on for 994 days since. There was a time, long ago, I didn’t believe that would be possible.

“If you die, I don’t think I could go on living,” I told her.

“Don’t say that,” she said, with tears in her eyes.

Now I know why I am writing this. I thought it was to discuss grief and its strange, creative, desolate forms. To reveal how quick the passing of time goes and the world changes. But writing this is a part of my ongoing grief process. The grief that may go on, beneath the surface, forever. I hope that in writing it, it may be of use to other people too.

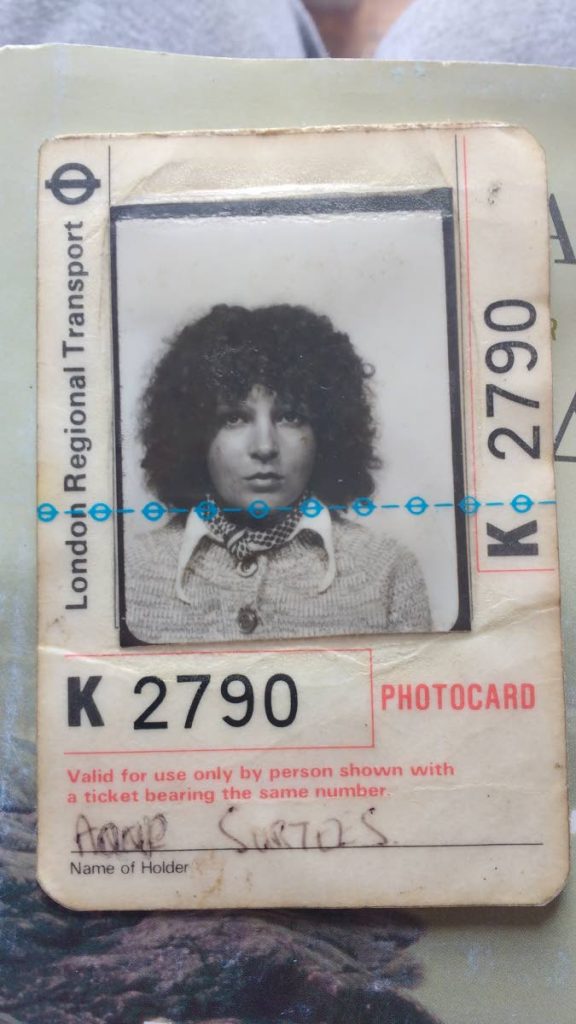

My mother died five days before David Bowie, of the same illness. It was the year many people died. It was the year of Brexit and Trump. She died before all that, before seeing how utterly changed the world is. Before I got a job at the UN. Before I went back to university to do a masters. Before my sister did the same. We both used the money she left us to further our education. She’d have liked that. Education, education, education was her thing. Learning, pushing oneself, never ceasing. Whether learning to play piano, ride a horse, climb a mountain, paint pictures, deliver babies, renovate a house or write a novel. Life was too short to not achieve things. She did all those things. And her life was short.

The other morning when I awoke, I could smell her house in France – the farmhouse she renovated from wreck to beauty. The wood-burning stove cinders from the night before, the wine fumes still in the air, the lingering afterthought of her delicious meals. The dogs curled up by the fireplace. My mother outside cutting grass. Croissants, a baguette, terrine, camembert laid out. Coffee brewed. The slight must of the wooden staircase and bookshelves. The nearby dairy farm wafting southwards. The summer meadows. The honeysuckle. All these smells came to me. I was thankful for that phantom aroma. It was her.

I still don’t know what grief is. It has not paralysed me nor triggered depression as I thought it might. There have been many happy times since she died. Before she died, she instructed me, in a seriously written letter, not to be overwhelmed by grief. I have honoured that request, mostly, though with some outpourings. I cannot hear hymns she used to sing without immediately being overcome.

But private, individual grief is perhaps the easier form. How we deal with grief as collectives, as families, is more difficult. Sadness does not wash over everybody at the same moments. Honouring memories means different things to different people. The realisation of shifted responsibilities and how we negotiate the right path forward, become tricky tests, post-matriarch.

My mum used to urge me to read books she’d finished. Some, like Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life, and Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage, I only read after she died. I felt bad when I realised that she probably wanted to talk about them with me. For her birthdays, my sister has begun a new tradition, Anne’s Book Club, where we give a book by one of mum’s favourite authors to each of her grandchildren. She’d have liked that.

The difficulty we have in grieving, as individuals and modern societies, comes from how we are taught not to linger on sadness. How completely detached we are from ancient mourning rituals. When too strong a sudden wave comes over me I exhale once, quickly, forcefully, as though pushing away the grief. Then I get on with whatever I'm doing. Expulsion instead of immersion.

I talk of mum every day, like she’s still here. I hear her, the outrageous rebel and hustler, recounting how, while breastfeeding, she would squirt milk across the room into the faces of my father’s awful sexist friends. I hear her telling of the time she drove the nursery van packed with kids and parents into Glastonbury Festival without paying, because security thought we were one of the acts. At the end of family holidays in Italy or Spain, she would often have run out of money and would simply pack up and drive away from the campsite, waving goodbye.

My wife has a habit of saying I love you, far too often. Because she never got to say I love you to her dad before he died suddenly. I had a long time to say I love you to my mum. But now I understand that too often is, in fact, never enough.

Comments

"How do you grieve?"