Suriname's infinite mystery, beauty

In a 4x4 jeep my wife and I are speeding south towards the Surinamese jungle. As we negotiated the morning rush hour we caught a glimpse of the intriguing mix of people and material surroundings in the gritty but captivating capital, Paramaribo.

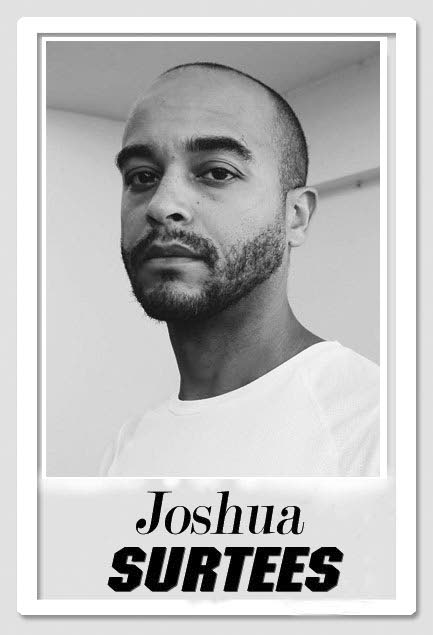

Now, a dozen kilometres down the highway, as long grasses, marshland, creeks and logging trucks colour the flat landscape around us, our tour guide Dustin eases off the accelerator pedal.

In an expansive area of flattened forest, a few elegant kapok trees stand visible on the horizon.

“Some people think that if you cut them down you will die,” Dustin says.

The government is clearing land for a housing complex but not even the developers are ruthless enough to fell these holy trees.

That first insight into Suriname stays with me. It speaks of the integrity of the people we encounter on our short stay here.

The unassuming beauty, naivety and authenticity of life here – multi-ethnic cultures preserved deeply from their sources in West Africa, India, Indonesia, China and the Netherlands – is an unexpected delight, even if some ventures into modern aesthetic design appear to have stalled in the mid-90s.

As a travel writer, I am sometimes loath to uncover hidden gems for fear of inviting off-grid tourists, but I feel certain Suriname will never be overrun. So close to fashionable, recognisable names like Brazil and Venezuela, it remains overlooked except by Dutch travellers.

And yet, it has everything an inquisitive traveller could wish for.

After noting that the people are very friendly, our next pleasant discovery is the food.

It begins at a roadside café with bakabana – plantain fried in flour and served with peanut sauce. It’s so good I could eat it daily, except I’d eventually die like Elvis from heart failure.

Later, we eat noodles drizzled with chicken sauce, barra (similar to saheena), thick broccoli and pea soups, smoked fish sandwiches – not dissimilar to gravlax – called bang bang, pickled mangoes, oddly textured Java apples, and a fruity hot pepper sauce known as sambal. We drink the heavily-marketed local beer, Parbo, a watery lager – refreshing when accompanying the salty, outrageously flavourful foods.

Passing disused bauxite mines (once a necessity in Suriname’s aluminium producing industry) and active gold mines (owned by Canadian and American mining corporations), we near Brownsberg – a lush jungle surrounding a huge man-made lake.

Dustin shows us the panorama of the lake from a lodge where adventurous holidaymakers sleep in hammocks. In the 1960s, countless villages in the valley were flooded to create a hydroelectric dam. Villagers were moved from their homes with the promise of new dwellings with running water and electricity. In places like Bieradumatu, Makambie and Kadju, some are still waiting for the promised supplies. The watery expanse is beautiful, but cruel.

Surinamese dancehall pumps out of the vibesy villages, that are supplied by big Chinese grocery stores selling everything from DIY tools to dried ginger.

As the tarmacked road ends and a wide reddish-brown mud track opens up, cutting into the forest ahead, Dustin invites us to ride on top of the jeep. Clinging to the side bars and wire mesh on the roof we surge fitfully over the bumpy, wet course until we reach a stony track that winds into the rainforest. All around us, vines plunge from the hanging branches of giant trees, and enormous blue marvel butterflies glint like winged sapphire jewels fluttering in the sun.

We park the car and hike to two waterfalls. Dustin tells us the sounds of honey creepers, screaming pihas, “forest roosters,” and frogs. He knocks the hollow-sounding trunk of a cavernous “telephone tree” to provoke the high-pitched catcall of one of the 200 bird species in the Brownsberg forest.

We hike past “Indian pipe trees” used to make rolling papers and tribal Amerindian penis gourds, the “Mabebe tree,” which heals itself into welts when cut, the female turtle vine which makes a tea to induce labour in pregnant women, the “Bush candle tree,” whose sap can be used as firelighters for barbecues, the “camina vine” used to make huts, and the parasitic abrassa tree that strangles other trees to death.

A family of Guyana red howler monkeys passes over us silently in the forest canopy and we gape in awe.

On our way home the rain begins to pour and the three-hour drive back to town becomes an endurance test in the dark.

The next day in the murky brackish water where the wide Suriname River meets the Atlantic Ocean, we spot playful young dolphins, grey on top, pink underneath, leaping and splashing around our boat. We visit an old plantation village originally settled by indentured Indian and Indonesian labourers and now only accessible by water. At dusk, on our way back to the jetty, snowy egrets roost in the riverbank mangrove trees as darkness descends over this magical land.

Comments

"Suriname's infinite mystery, beauty"