1950s life reflects Trinidad decades later

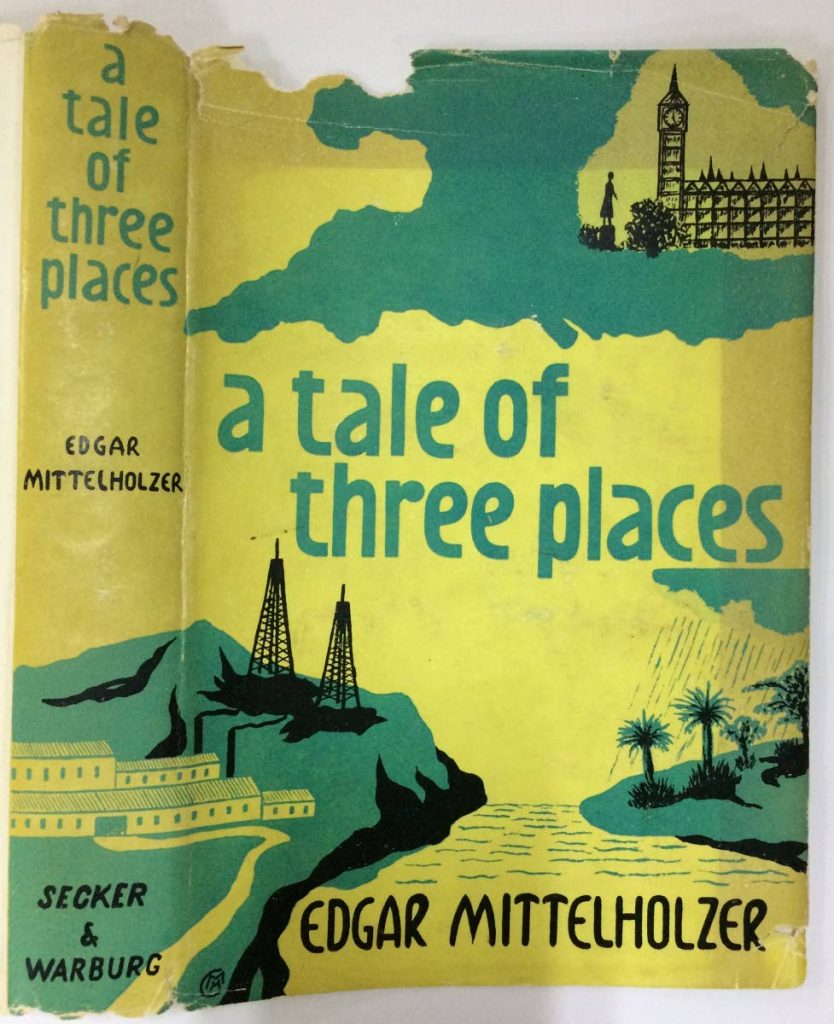

KEITH JARDIM reviews Edgar Mittelholzer’s Novel A Tale of Three Places.

One of the first and best critics of Trinidad’s social problems after World War II, problems that would eventually lead to the present state of unrest, religious zealotry and criminal industry in the island, is the Guyanese novelist Edgar Mittelholzer (1909-1965). His 1950 novel A Morning at the Office analyses the post-plantation mores of 20th-century Trinidad.

But Mittelholzer’s far better achievement is the still-out-of-print A Tale of Three Places (1957). In this novel, divided into three parts – Book One: Trinidad, Book Two: England, Book Three: St Lucia – the first part could easily stand alone as a self-contained narrative, a moderate-length novel and a genuinely fine accomplishment that shows why an upper-middle-class young man, Alfred Desseau, leaves Trinidad, abandoning his job, family, friends, and girlfriends to be something of a layabout and more in England; and then later, in Book Three, in St Lucia, where he pursues an ideal of love in a rainy Eden while remaining open-minded to possibilities of a different kind of island life, mainly through how we love one another – in particular, the love between men and women.

Alfy isn’t the only one who has departure in mind: sickly sweet middle-class Trinidadian Elsa goes to England with her parents, mainly in the hope of reuniting with Alfy; and Sidney, a violent man from the all-too-familiar nouveau-riche class of Trinidad, pursues Elsa, love and marriage on his mind, threatening to kill Alfy if he touches her. Sidney even has a gun, which he waves around to back up his threats.

The last chapter of Book One: Trinidad is titled Prelude to Departure. Escape is on Alfy’s mind, yet he senses wistfully the beauty in Nature, in the Trinidad landscape:

“He had to come to a halt and gasp at the loveliness of the upper hillsides which were aflame with immortelle blooms – a cool, soft, scarlet conflagration poised as though to sweep down in a benign blast upon the cultivated lands below and the tiny cottages along the river’s edge. The scent of the river came to his senses – a mossy, clear-water scent tinged with a faint vegetable reek… the stinging muskiness of some wild blossom joined the scent of fresh water, exotic and seductive – almost aphrodisiac.

An aroma one could follow as though it were a diablesse of the woods beckoning a promise of fleshly delights in the shadow of some vine-coloured vault.”

I was surprised at how persuasively Mittelholzer depicted my thoughts, my yearnings and my friends’ for opportunity, love, hope, ambitions and friendships, as if Mittelholzer had known me and written me down – all of us. There are even conversations and incidents in A Tale of Three Places that seem freakishly lifted from the late 1970s to 1990s and taken back to the 1950s. To see and hear people involved in the same situations I experienced with my friends being repeated in living rooms at parties in Mittelholzer’s 1957 novel, similar lives confronting the same problems we had, is uncanny.

In the St Lucia section the search for a different life, a better one with the sweet melancholy pull of a Jungian Eden quest, is revived but sobered. (Alfy’s experience in Trinidad tempers it.) Discussions of values, of political independence from England and human purpose, ensue. There are exquisite descriptions of weather and landscape in this section: both appear to act consciously, as they do in many of Mittelholzer’s books. The days of blue and green, so dew-clear and silent you can taste hope in the air reveal all the hisses of the rotten Eden story: an old and still-authentic plantation, with a couple of scheming overseer types with hints of temptations brought on by the powerful and powerless, remains.

Yet it’s here, in the spectacular setting of St Lucia, where nature is so profoundly, mesmerizingly and beautifully intrusive, that the reader can’t resist the idea of another life.

Mittelholzer’s contribution to building Caribbean civilisation in his accomplished works may have just begun, as some of the new criticism on his work by Kenneth Ramchand, Juanita Cox, Rupert Roopnaraine and Raymond Ramcharitar implies. If only more people would read him.

* Keith Jardim is the author of Near Open Water, a collection of stories. He teaches fiction workshops at the Naipaul House in Port of Spain, Trinidad.

Comments

"1950s life reflects Trinidad decades later"