TT's green road

Kermit the Frog was on to something when he sang it’s not easy being green.

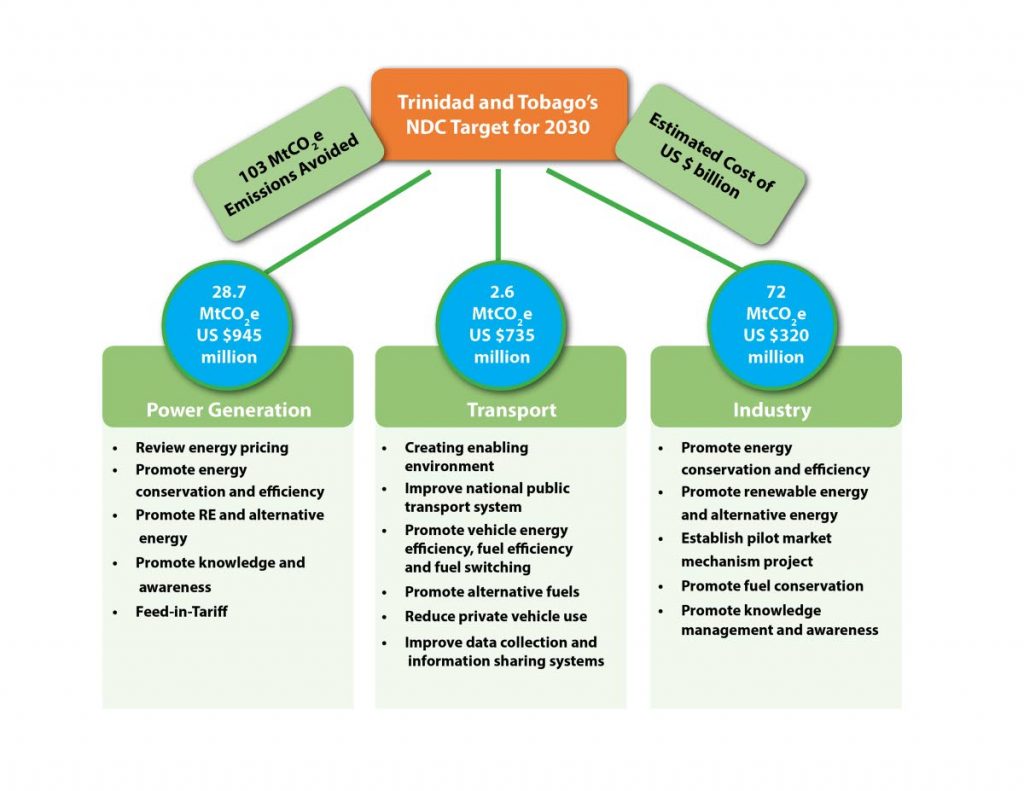

Trinidad and Tobago’s transition to a more environmentally-conscious society, in keeping with the terms of the Paris agreement on climate change, is estimated to cost US$2 billion if the country is to reach its target of cutting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 15 per cent — or 103 million tonnes — from what it is today, cumulatively, by 2030.

Even though the country accounts for less than one per cent of greenhouse gas emissions, as a small island developing state, TT is at risk from the adverse effects of climate change, including rising ocean temperatures, changes in precipitation, coastal erosion— already evident in places like Cedros and Mayaro – and as hurricanes Irma and Maria proved last year, the increased likelihood of being affected by more intense tropical storms.

The United States is the only country in the world that has not signed on to the Paris agreement, a global commitment to reduce greenhouse emissions that came into force in November 2016. Even though TT was a signatory, it didn’t actually ratify the agreement (make it effective as policy) until February 2018.

“We didn’t just rush in. We looked very carefully at what was required of us, the cost and effect on the country, and when we were satisfied the arrangement was what we could live with, we did,” Prime Minister Dr Keith Rowley had said a few days after the signing, acknowledging that some of the concessions to TT will be on hydrocarbon reductions — the primary economic earner for the country.

To combat climate change, the Paris agreement recommends a nationally determined contributions (NDC) outline to help each country structure its goals according to its ability, as part of its commitment to achieving a low-carbon output future.

“The NDC is basically each country’s public commitments to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and is tailored to meet their own national circumstances, capabilities and priorities for the post-2020 period and is an important element of the Paris agreement, making the transition to a low-carbon economy inevitable,” said Sasha Jattansingh, an environmental engineer and public policy consultant who developed TT’s NDC Implementation Plan. That document has been submitted to Cabinet and once approved, will be TT’s guide for reducing carbon emissions and achieving the country's Paris agreement goals. It’s been with Cabinet for nearly a year.

Most of TT’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the power generation, transportation and industry sectors.

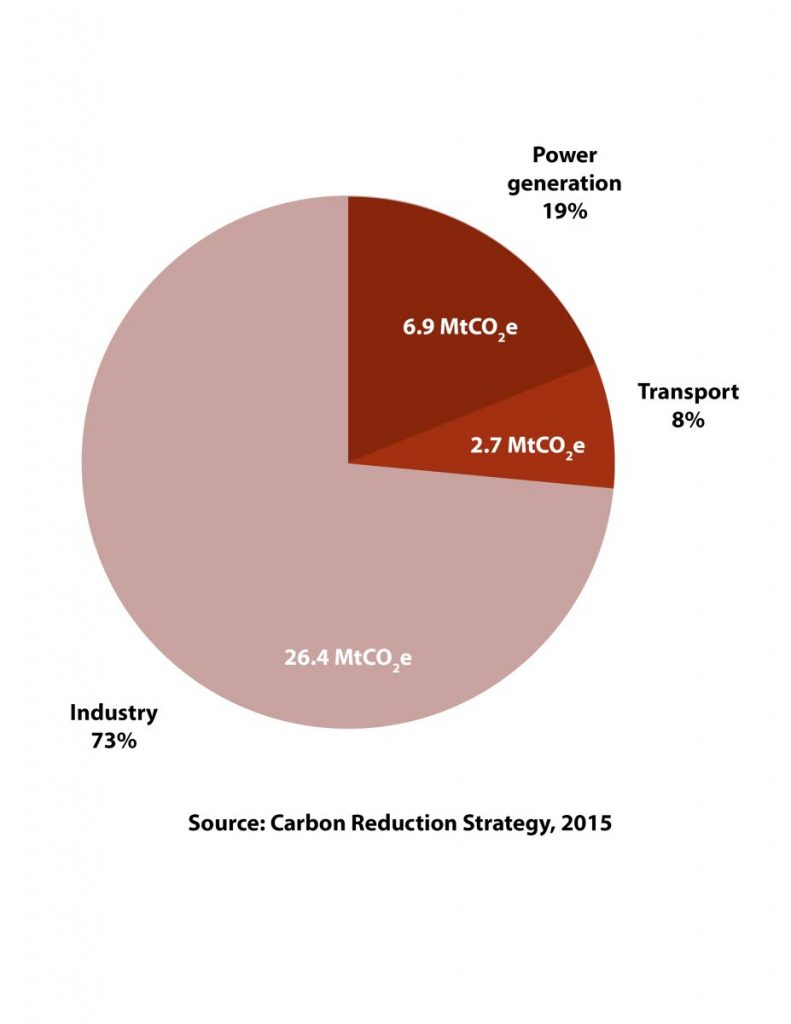

According to the Ministry of Planning and Development's Carbon Reduction Strategy (2015), industry is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the biggest contributor to the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, producing nearly 27 million tonnes annually, or 73 per cent. Electricity generation is 19 per cent, producing nearly seven million tonnes, and transport contributes eight per cent or about three million tonnes.

Government has sought the assistance of the United Nations Development Programme to help it figure out an NDC strategy that focuses on these sectors.

Most of the funding for these lofty aims may be accessed through various international environmental funds, including the Green Fund. Some Caricom countries have already tapped these resources, with Grenada receiving US$42.16 million for its climate-resilient water sector project, and Barbados, US$27.6 million, also for a water sector resilience nexus for sustainability project.

The Public Sector Investment Programme and the Green Fund will be domestic sources of funding, through which Government hopes to focus on public transportation emissions, reducing that by 30 per cent or 1.7 million tonnes, by 2030.

Government has already announced some of its initiatives, including a thrust to make compressed natural gas the fuel of choice for fleets at the Public Transport Service Corporation (PTSC), recycling programmes like iCare, and proposals to close landfills and more effectively manage waste disposal.

There’s also talk of producing ten per cent of electricity from renewable resources — including waste. The challenge to that, however, is that currently, while TT’s electricity is produced from cleaner burning (although non-renewable) natural gas, the country already has an overcapacity of electricity — TT needs about 1.2 megawatt hours but produces 1.9 megawatt hours. And because the state electricity commission, TTEC, already is engaged in take-or-pay contracts with electricity providers, it’s hard to modify the current system.

Nevertheless, Public Utilities Minister Robert Le Hunte has said renewables are the future, and the ministry is looking to partner with private sector firms to produce electricity on a small-scale to start — perhaps three megawatt hours.

While Jattansingh acknowledged Government’s attempts to spur some kind of culture change, she noted the continued lack of an official coordination strategy for low carbon development, with projects and initiatives among public, private and civil society sectors. Without a guide, there’s an unwillingness or even lack of motivation from partners — like the private sector and individuals — to start making more meaningful changes.

“It’s happening in a piecemeal manner with limited sustainability of the action and little or no monitoring and evaluation to determine if overall policy goals are being met by these initiatives,” she said.

The NDC Implementation Plan can serve as such a coordination strategy since it is the initial road map to coordinate TT’s transition to a low carbon economy. Continued delay by Cabinet in approving the NDC Implementation Plan implies a lack of political support and commitment towards low carbon development and greening the economy, Jattansingh added.

The private sector should be the leaders of innovation and investment in finding solutions for sustainable development, but it requires long term, predictable and supportive policy and regulatory regimes which would facilitate the transition to a low carbon economy, she said.

Climate resiliency and sustainable development is, however, a potentially lucrative business. The UN Environment Programme estimates that US$5-7 trillion is required annually to finance sustainable development and the Climate Group estimates that US$90 trillion is required to achieve the aims of the Paris agreement over the next 15 years.

Jattansingh emphasised the importance of private investment in a green economy.

“The private sector has a significant role in achieving the Paris agreement and the SDGs (sustainable development goals) through mobilising climate investments and as a driver for technological change and innovation towards low carbon technologies as well as enabling economic growth and employment opportunities, particularly in ‘greening’ existing industries or new green industries.”

Comments

"TT’s green road"