T&CP’s role in the climate crisis

The latest United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report makes it clear that addressing the climate crisis, and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, requires key changes to land use regulations, which, in our case in TT, requires action at the Town and Country Planning Division (T&CPD)

According to its website, “for a decade, UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report has compared where GHG emissions are heading against where they need to be, and highlighted the best ways to close the gap.”

The nation is seeing some, albeit not nearly enough, progress, particularly as it pertains to awareness, dialogue, and specific high-level policy directives. However, signing onto multilateral climate agreements and being able to recite the Sustainable Development Goals means little without transformative action that filters down to regulatory agencies in particular.

It is clear from the report that urbanisation can play a key role in addressing the current climate crisis.

Unfortunately, our attitude in TT considers urbanisation and environmentalism to be opponents instead of allies.

Our urban planning ideology, whether we acknowledge it or not, is inherently based on anti-urban notions of development, or an arcadian concept in which we are supposed to live in commune with nature. The result is the idea that dense agglomerations of people, multi-family living arrangements, and – consequently – highly social and intimate urban environments should be reduced (decentralised) as much as possible.

These are thought to be antithetical to the notion of liveability. Where density and multi-family living is necessary, it should be designed to provide the illusion of a bucolic setting.

This ideology has found its way into the very code that determines our urban form, which the UK Government Office for Science defines as “the physical characteristics that make up built-up areas, including the shape, size, density and configuration of settlements. It can be considered at different scales: from regional, to urban, neighbourhood, "block" and "street.”

Due largely to our land use regulations or code, our environment has degenerated into what we planners define as automobile-oriented suburban sprawl, which the report calls the “least sustainable model of all.”

One reason for this is that sprawl makes it very difficult to provide sustainable transportation – a sector that contributes enormously to GHG emissions.

Street networks made up of loops and cul-de-sacs – where few streets connect – combined with other anti-pedestrian and anti-bicyclist design factors create longer and circuitous routes, and conditions that are only comfortable for driving. This renders walking and bicycling unattractive modes of transportation. An important point, since “short journeys account for two thirds of transport emissions in urban areas and could be replaced by active modes.”

Just this week I read a recent outline planning permission letter from T&CPD for a land development scheme, which stated the typical requirement that “proposed roads must be designed in such a manner as to permit integration with the existing road network. Alternatively, proposed roads must end in a cul-de-sac.” The latter, frequently employed option leaves the door wide open for inefficiency.

Low-density development, where most homes are detached single-family structures on 5,000-square-foot or larger lots of land, leads to an inefficient dispersion of people, which leads to fewer potential riders of public transportation within any given catchment area. The per-capita cost of providing public transportation will be higher.

Another reason is that the single-family homes found in sprawl are typically larger than multi-family units in urban centres.

According to the report, “future floor area demand is a crucial variable for GHG emissions and more intensive use can result in significant reductions of both material and energy related emissions,” as the typically larger homes require more material to construct and more energy and water to meet household needs.

Further, it states that the process of urbanisation, that is, people moving from suburban and rural areas to dense urban centres, can reduce GHG emissions, but “in some locations, spatial planning prevents the construction of multifamily residences and locks in suburban forms at high social and environmental costs. A reform of planning rules could bring about multiple benefits in this regard.”.

This is especially critical since average household size tends to decrease as income increases. This creates more household units, which are no longer sharing resources as efficiently as larger ones do. These smaller households downsizing into multifamily dwellings can offset this. Our average household size has gone from 4.1 in 1990 to 3.3 in 2011 – converging to the US size of roughly 2.6.

As the report also notes, buildings can have a life span from 25 years in some East Asian countries, to over 100 years in European countries. The way that we lay out streets can affect us for an even longer time. What we build now and how we build it will be with us for a long time.

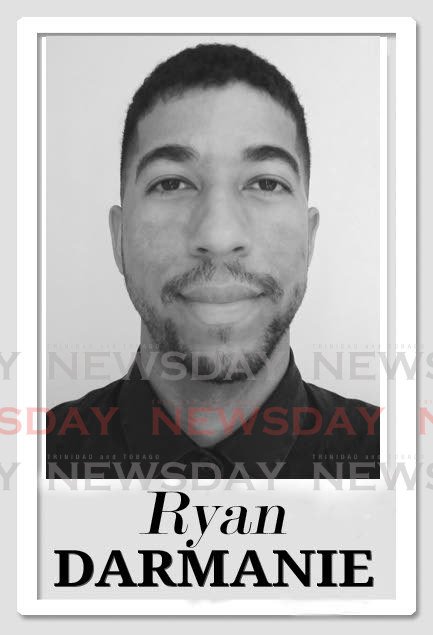

Ryan Darmanie is a professional urban planning and design consultant, and an avid observer of people, their habitat, and the resulting socio-economic and political dynamics. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or e-mail him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"T&CP’s role in the climate crisis"