Trinis led the way for Africa

For decades, TT has been at the centre of the quest for answers to the question by poet Countee Cullen, “What is Africa to me?”

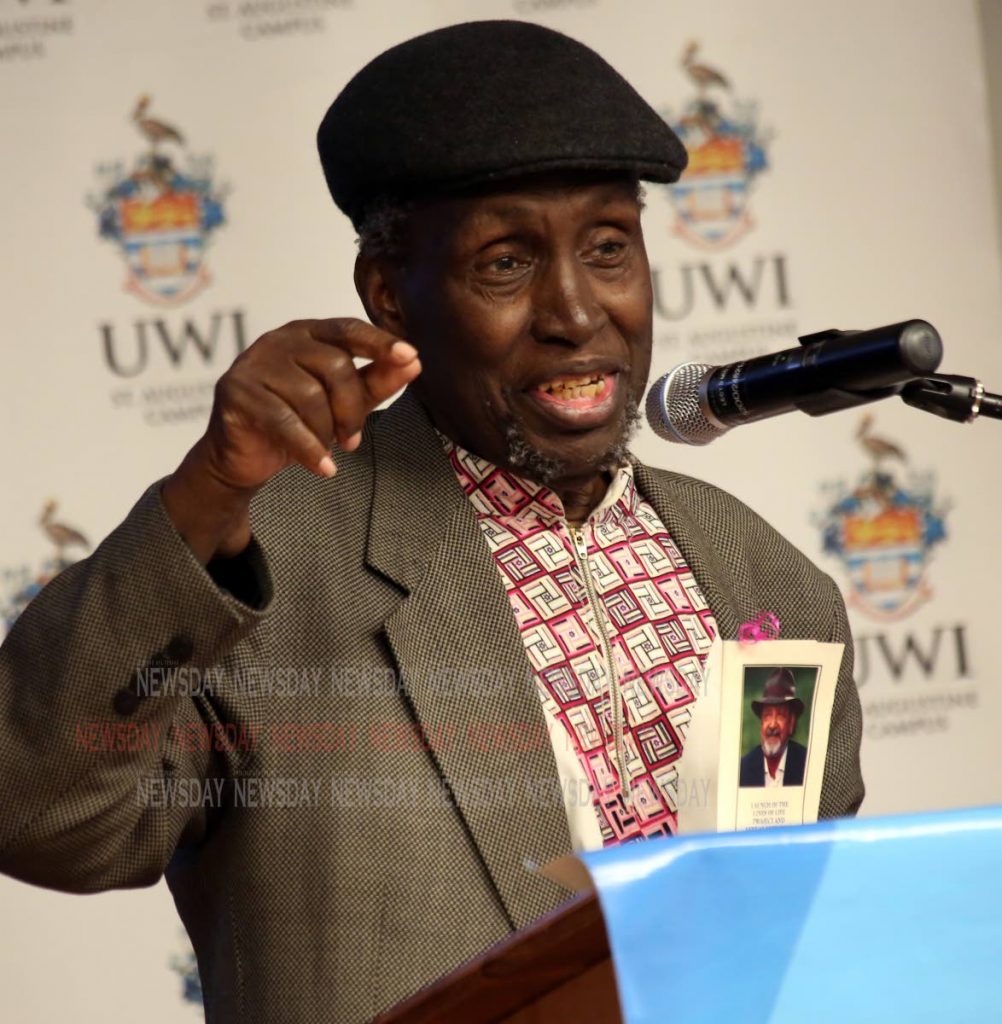

This connection was explored by award-winning, world-renowned Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o at the launch of the Lines of Life project and annual memorial lecture at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine, yesterday.

The project is a website bringing together discussions, research, essays, video interviews, and general information on the life and works of the late Trinidadian Nobel laureate Sir VS Naipaul.

Thiong’o said there has been debate about the place of Africa in the consciousness of people on the African continent and the diaspora.

He recalled an argument between Naipaul and Barbadian novelist, essayist and poet George Lamming. Naipaul argued that Africa had been forgotten by the Caribbean and mention of the continent produced embarrassed laughter, while Lamming said it was because Africa was not forgotten that the Caribbean produced such laughter.

Thiong’o questioned Naipaul’s argument, since the influence of Caribbean people, including Marcus Garvey of Jamaica and Toussaint L’Ouverture of Haiti, regarding Africa has reached all over the world.

“Henry Sylvester Williams organised the First Pan African Congress in 1900, George Padmore followed suit with the momentous fifth Pan African Congress at Manchester in 1945, and Stokely Carmichael, aka Kwame Ture, organised the Black Power Movement.

“There is also Claudia Jones, who would not let prison or exile or dislocation deter her from activism. She was the founder of West Indian Gazette in 1958, the first major black newspaper in England. Her career of social activism in Trinidad, the USA and Britain, climaxed in her founding the Notting Hill Caribbean Carnival in 1959.”

Thiong’o said he and Naipaul had met only once, but had several African connections. Both their wives (in Naipaul’s case, his second wife, Lady Nadira Naipaul) were born in Kenya, and Naipaul held a writing fellowship at Makerere University College just before he did. Naipaul was also on the jury which awarded him the 2001 Nonino International Prize for the Italian translation of his book Moving the Centre.

He explained the book was based on the struggles of the University of Nairobi in the 1960s to stop the literature curriculum from being Eurocentric and instead make Africa the centre. He said Caribbean writers of the 1950s and 60s were an important part of the debate and the solution.

It resulted in residences for Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite and Lamming, as well as visiting lecturers from Barbados, Jamaica and Nigeria instead of Europe.

Thiong’o said he was introduced to Caribbean literature in 1961, when he borrowed In the Castle of My Skin, by Lamming, from a history professor as an undergraduate at Makerere.

“I felt Lamming’s narrative power spoke to me and my Kenya situation so directly that, as I have acknowledged in my memoir Birth of a Dream Weaver, it influenced the theme and the writing of my novel Weep Not, Child.”

However, he became engrossed in Caribbean literature while at the University of Leeds, England from 1965-1968, as it opened a new world to him.

“It was through the eyes of Caribbean literature that I had been able to see and critique the Eurocentric basis of our organisation of literary knowledge. The title of my book Homecoming was meant to be a tribute to a literature that had made me find my way back home.”

To illustrate the global reach and effect of Caribbean writers of Lamming and Naipaul’s generation, Thiong’o told of how he was put in a maximum security prison in 1977 for his theatre work with the Kamiriithu Community Centre in Kenya. He was released a year later thanks to a campaign led by several London-based Caribbean activists and intellectuals, including Trinidadian John La Rose.

Later, many Kenyan progressive intellectuals were imprisoned after an attempted coup.

“The Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya was formed in July 1982, with John La Rose as the chair, and the same group of Caribbean intellectuals who had been at the forefront in the campaign for my own release now making the core of the new committee.

“John La Rose, who never lost his roots in trade unionism in Trinidad, ran the New Beacon bookshop in London, from which he inspired an international black intellectual movement which combined within it Third Worldism and workers’ movements. Among the speakers at the inauguration of the Kenya committee was CLR James...

“The fact that any regime anywhere finds it necessary to imprison writers, force them into exile or even kill them bespeaks of the power of literature and the centrality of writers and writing in society and the world.”

Recalling his time in prison, he said he would watch birds fly outside his window during the day and wish for wings. He would fantasise about what he would do with those wings – visit his family, create mischief for his captors without their knowing the source of their ills, or simply walk the streets. He realised that through his imagination he was escaping his captors. That realisation led him to write the novel Devil on the Cross in prison on toilet paper in the Gikuyu language.

Imagination, he said, was his wings of glory, and was as important to human beings as the body and soul. He said while the body needs food and water, the soul needs spiritual nourishment. One system of nourishment was through the arts, which are enabled by imagination.

“That is why, in every known human society, there have always been artists, as storytellers, singers, dancers or painters. Even the cave dwellers had developed rock drawings.

“The role of the arts, once produced by imagination, is to feed the imagination the way food feeds the body, and morality the soul.”

He called artists and writers angels of imagination, who make people look, feel, touch, and listen again. He said Naipaul in particular had the gift of sight.

“And no matter how uncomfortable he may make you, Naipaul forces you to look again and again. No reader can be indifferent to his work.”

Comments

"Trinis led the way for Africa"