Mutiny and survival

SHEREEN ALI

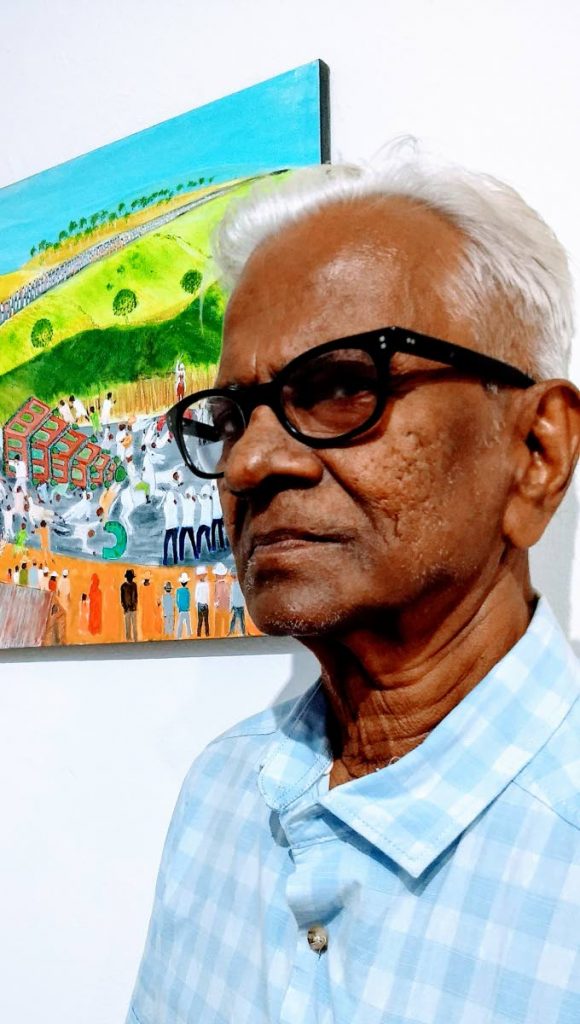

“I cannot deny my roots. I’ve always had a desire to find out where I came from. And I couldn’t suppress all these images that were burning in my mind, seeking release,” says the mild-mannered David Subran, an educator-turned-artist whose current exhibition at the Frame Shop in Woodbrook tells a poignant story of East Indian trauma, journey, indenture and survival in Trinidad.

The oil-painting exhibition opened on May 25 and runs until June 22.

If current history books don’t always tell the Caribbean’s stories and heritage from a Caribbean point of view, then Subran’s art is a way of visually documenting and expressing a sense of collective self for the descendants of Indian immigrants in Trinidad.

While some people may know bits of their history, many haven’t a clue, or have only the vaguest notions of the journeys and actual experiences of their great-grandparents and other ancestors who came here to shape a better life for themselves.

Subran’s exhibition, The Story, takes viewers on a visual, historical journey from the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny in Lucknow, India, where brutal British reprisals forced many Indians to emigrate, to more recent experiences of Indian indentured life on Trinidad sugar estates, such as getting up by the call of a conch shell in pre-dawn moonlight to work from dawn till dusk. The paintings are in a style like naïve art, using childlike simplicity and frankness to portray historically researched or personally experienced events. Subran, a self-taught artist and retired UWI lecturer in education, is 79.

The art has varied themes. There’s a portrayal of an eerie, drought-parched Indian landscape of famine, desolation and desperation, surreal in its suggestion of emptiness and death, a huge burning sky scorching most plant life and agriculture beneath it. Many Indians came to Trinidad to flee such harsh environmental conditions.

Another painting shows British officers tying Indian mutineers to cannons to blow them up (yes, this happened). Yet another work shows the brave queen of Jhansi on horseback, her sword in the air. This was an Indian queen who, after her husband’s death, had all her property stolen by the British Empire (based on the British doctrine of lapse which disinherited widows without a male heir). In response, the Indian queen amassed an army and joined the mutineers, fighting back with all her might until the British killed her.

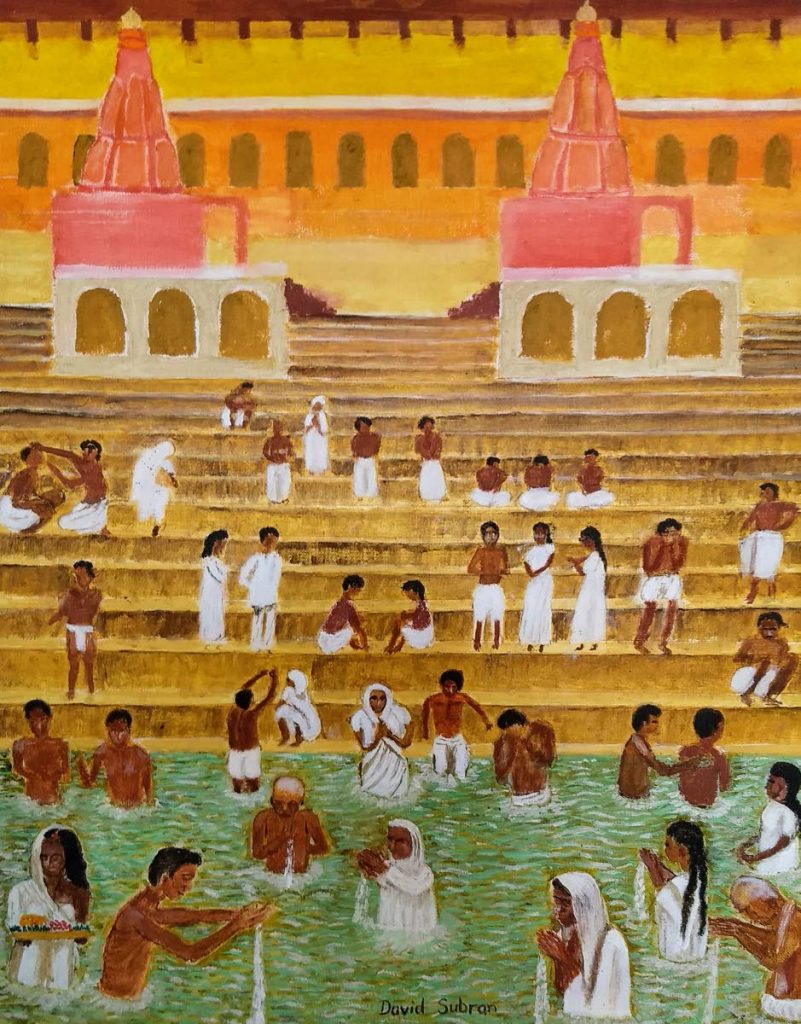

There’s an image of a recruiter spinning tall tales of the good life in Trinidad to unsuspecting Indian peasants. Another image shows Indians bathing in a river at Varanasi before boarding a boat to take them down the Ganga river to the Caribbean-bound ships.

The painting Below Decks – Family Quarters reminds viewers of the hardships of the long sea voyage, where an average ten to 40 people would die on each trip across the Black Water, or Kala Pani, of the Atlantic Ocean.

Subsequent paintings show images of Indian immigrant life in Trinidad, including fanning home-grown rice which people grew to sustain themselves; harvesting sugar cane; selling vegetables in Chaguanas market; Tamil men walking on burning coals; and the Hosay Massacre of October 30, 1884, when Muslims and Hindus united for the Hosay procession and 17 were killed by the British at Cross Crossing and Toll Gate in San Fernando.

Bhaisas Return to the Pen is a pastoral image with a surreal sunset sky, showing a herd of buffalo going to their pen at dusk, responding to the gong-like sound of a boy striking a discarded disk plough.

In an interview, Subran emphasised that the legacy of Indian immigrants to TT means much more than just the foods they brought, or the new dress styles, language forms, music and religious traditions which entered Trinidad in the 1800s with the onset of indentureship. Fundamentally, the Indian heritage also includes the huge sacrifices these early Indian immigrants made for their children and later generations of family: sharing, thrift, self-discipline, family-building and community self-help were crucial. Indian self-help took many forms and included building their own schools when no education was made available to them in colonial times: one painting, Cowshed Schools, shows this idea.

Subran began his career as an apprentice welder with the Shell company, where he learned technical drawing skills. He would make quick sketches for equipment to be fabricated.

“But I had such a busy life that I did not have time to concentrate on painting until ten years ago,” says Subran, whose grandparents were born in India. His father (born in Trinidad in 1913) worked as a tailor in Chaguanas and as a factory clerk at the Woodford Lodge sugar factory, responsible for delivering molasses.

“I am very close to this theme (of Indian heritage),” comments Subran, whose grandparents were from the Indian village of Bansdih in the province of Ballia in Uttar Pradesh, a state in northern India.

“My grandmother came from India; my uncle was born in India; and my father was born here but had a brother born in India. And I grew up in Chaguanas, where there were all these artefacts and evidence of indentureship. People tell me of their experiences. I saw people who actually came from India.

“So it was very close to me. Indian culture fascinated me and I wanted to explore it in greater depth. Imagine, people landing in a country, they can’t speak a word of the language, nobody understands them, some people despise them, and they come here now as ‘strike-breakers’ to replace the slaves.

“So they could have been very lonely, but their sense of community and their strong culture helped them to survive and even prosper.

“I listen to people saying things like: ‘There can be no Mother India’ and so on, but I cannot shed my heritage. I enjoy being in Trinidad, I love Trinidad, I don’t want to go live in India, but I cannot deny my roots.”

“As a boy I had close contact with the barracks. The painting Early Morning Cooking in the Barracks shows what the people lived in. During the daytime, this thing was hot like an oven. They cooked there. The man would leave 4 o’clock in the morning for the fields as the conch shell blew.

“My father used to converse a lot with me about how the life was. And I also witnessed these things first-hand in the 1950s because I worked for a short while as a child worker at Woodford Lodge Estate, helping to load cane.”

His art shows scenes of harvesting cane, such as a mule-driven winch with a cable lifting loads of cane to a derrick, and the ever-present figure of a white overseer on a horse.

There is also a painting of a 1949-era Chaguanas street scene, with an Indian woman selling produce.

“I might have been like the boy pushing the box cart,” quips Subran: “My father always had me with a box cart.”

Going to market every Saturday morning was (and still is) an important Indian family ritual, says Subran, who added: “We all planted rice.”

“Some Indians received five acres of land, during a certain period of about 20 years, for not going back to India. Our five acres of land was by the Caroni Swamp. I had a big pond they dug, they used to plant rice. Most homes in Chaguanas had a big tall rice box. And people would plant their pumpkin and different things.

“That is what helped the indentured Indians to move up and to become self-sufficient, selling the surplus.

“One of the motivational reasons for this art series is that I look now at their descendants, and I sense some people take these things for granted. I wish to remind the younger generation of the hardships and endurance of their ancestors, who suffered so that they may prosper. People of today should not take that sacrifice for granted but try to build on that foundation. These people sacrificed all for their children.”

* The Story runs at the Frame Shop, corner of Carlos and Roberts Street, Woodbrook, until June 22.

Comments

"Mutiny and survival"