Neither paean nor pedestal

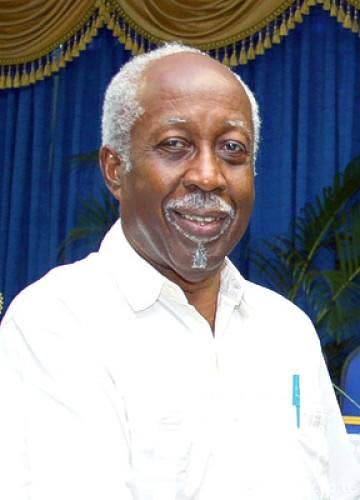

REGINALD DUMAS

ON HIS third voyage in 1498, Christopher Columbus came across an island which he named Trinidad (there are still people in this country who prefer to use the Eurocentric colonial word “discovered”). In sailing west to reach east, Columbus had the right idea. But there wasn’t any Panama Canal at the time, and he kept bouncing off land, unable to reach the Pacific Ocean. However, he deserves marks for thought and determination. Equally, he deserves nothing but vilification for the mayhem he initiated, and fostered, in the western lands he and his European successors reached.

In his biography of Bartolome de Las Casas (the so-called “Protector of the Indians”), Evan Jones writes: “In 1492” (the date of Columbus’ first voyage) “Hispaniola…had been inhabited by more than one hundred thousand Indians of the Arawak tribe…Now” (in 1502) “the island was ruled by the Spanish, and the Arawaks had already begun to disappear from the family of man…To the conquerors, the Indians were a sort of animal…Consequently, they could be murdered, tortured, or enslaved without any question of right or wrong.”

It was Columbus who had started the rot, gratefully expanded by later arrivals from Spain. They forced the Indians into bondage to look for gold, they smashed babies’ heads on rocks, they cut off women’s breasts and men’s hands and noses, they Roman Catholicised “at the point of a sword” (Jones), and so on.

Nor did Columbus spare his own European settlers. Those who grumbled and rebelled because they felt he had conned them (which he had) into believing that great riches lay in these new lands were slaughtered without mercy by his goons. So extreme was his cruelty that the Spanish monarchs who had sponsored his trips sent a team which took him back to Spain in chains.

I now hear that Columbus is “a part of our history” and that his Port of Spain statue should therefore be left alone: if you remove it, you would be “rewriting history,” and that would mean changing several things, like the country’s name (which is, apparently, Trinidad. Good to know). I fully agree that Columbus is a part of our history, but the logic of these arguments wholly defeats me.

The Spanish ambassador to TT, Javier Carbajosa, seems comfortable with it, though. In a published letter, he says: “History cannot be rewritten to the taste of the consumer. It is what it is…(and) is part of our legacy. We should accept it…”

The letter oozes sarcasm and condescension, as if he were a Spanish conquistador chiding the natives, and ends with what sounds very much like a threat: “I think it would be wise to think twice about the consequences of our actions.” What “consequences” does His Excellency have in mind? And since Columbus statues in the USA are also being targeted, has his Washington colleague written in the same vein to the American people?

I found Carbajosa’s letter impertinent. More, he neglected to tell us that, not quite one year ago, the remains of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco were exhumed from the fancy site (the Valley of the Fallen) where they had lain for over four decades, and reburied in a less than exalted cemetery. The Spanish Prime Minister, Pedro Sanchez, was delighted: the move, he said, closed “a dark chapter of our history. No enemy of our democracy deserves a place of worship or of institutional respect. This is a great victory for Spanish democracy.”

Was Sanchez “rewriting history?” Or correcting a historical wrong which his government (and many Spaniards) didn’t “accept?” And can Carbajosa assure us that no mosque left by the Moors who occupied Spain for nearly 800 years has been converted into a Roman Catholic cathedral? Has Spain yet “accepted” its history?

As a general rule, should we view historical figures in a vacuum, ignoring the contexts in which those figures were located? If so, should there be monuments to Adolf Hitler, who was a major 20th century phenomenon in world history, and whose influence is still being felt? If not, why?

I repeat: Columbus is part of our history. We cannot excise him from that history, nor should we try. But we must remember what he was: an ultimately failed explorer, a torturer, an enthusiastic practitioner of genocide, a plunderer for whom material wealth held more than an ordinary attraction. Such a record doesn’t, in my opinion, entitle anyone to either paean or pedestal.

His statue should be removed. But it shouldn’t be thrown away. I support those who say it should be put in a museum of our history. Such a collection, long overdue, should help us improve our generally minimal familiarity with our past.

Comments

"Neither paean nor pedestal"