Marias’ magical gift

KEITH JARDIM

concludes his review of the writings of Spanish author

Javier Marias.

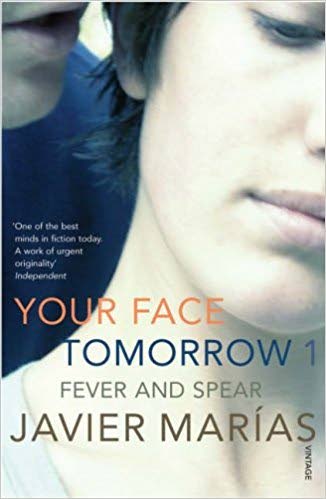

In his novel Your Face Tomorrow: Volume One: Fever and Spear, set in Oxford, England, Javier Marias introduces us to Jaime Deza, separated from his wife in Madrid and somewhat adrift in London. There he meets an old friend, Sir Peter Wheeler, who recruits him for British Intelligence.

Much of the novel concerns how this happens.

They spend much of the night talking, with Wheeler interviewing Deza, who eventually tells Wheeler about his father, and his denunciation by a former friend in the Spanish civil war.

Deza’s ability to see behind the masks that people wear makes him invaluable to Wheeler.

The sense that Marias is writing extremely close to actual events in his life, and of course to the lives of his friends and family, is uncannily there.

Marias has a magical gift of blending the elements of fiction with those of autobiography and history, of letting you think you’re actually getting close to a real someone who is sharing, carefully and hesitantly, secrets about actual life, its horrors and disturbances, that can be revealed only through disguises channelled into digressions and artful indirection, a process ultimately resulting in a confrontation with truth – of some kind.

The reader quickly learns to trust the narrators because they admit to their insatiable curiosity and not knowing, their fear of being misled; they are ever cautious, instinctively in touch with the omnipresent unease in our world, and they doubt.

What they do know, they assert often in an odd voice graced with humility and a register of distant, but still acute, pain, a signature of true experience earned the hard way.

“Telling is almost always done as a gift, even when the story contains and injects some poison, it is also a bond, a granting of trust, and rare is the trust or confidence that is not sooner or later betrayed, rare is the close bond that does not grow twisted or knotted and, in the end, become so tangled that a razor or knife is needed to cut it.”

The gist here seems to be that there really is no truth, and for this reason human existence is all the more dangerous, precarious, fragile.

The fundamental importance of democratic societies looms: without them things happen violently and suddenly.

People disappear. They are murdered.

As one of Marias’s narrators says: “Listening means knowing, finding out, knowing everything there is to know, ears don’t have lids that can close against the words uttered, they can’t hide from what they sense they’re about to hear, it’s always too late.”

* Keith Jardim teaches fiction workshops at the Naipaul House, St James.

Comments

"Marias’ magical gift"