Imagining a city

Marina Salandy-Brown

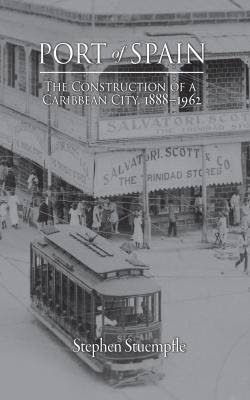

“A disappearing city,” is how Stephen Stuempfle described Port of Spain in a session of this year’s NGC Bocas Lit Fest. His book Port of Spain: The Construction of a Caribbean City 1888-1962 was the basis of a discussion between the author, conservationist architect Rudlynn Roberts and historian Bridget Brereton, and led by writer and Newsday editor-in-chief, Judy Raymond.

When one thinks of city landscapes the image of buildings pops up in our mind’s eye, but Stuempfle turns that on its head by focusing rather on how human history of interaction and ambition, our arts and culture have shaped that material landscape.

The NGC Bocas Lit Fest was started eight years ago as a celebration of our literature and a means of encouraging our people to re-engage with it. Doing that in an urban, public place was essential to the plan. It was a touch of genius that our wonderful National Library was constructed in downtown Port of Spain, the traditional heart of the city, and that the then Ministry of Arts and Culture invited us to use, as the home of the annual festival, that well designed, people-friendly building that opens onto the many historic buildings and roadways of Port of Spain and onto its iconic Woodford Square. We are fortunate too that the National Library abuts the culturally and historically important Old Fire Station and that the library’s architect, Colin Laird, was able to imagine the old and the new together in a continuum and achieve the architectural linking of the 1890s stone building with the floating, almost ephemeral white mass that is the modern library.

Uniting the different elements of the sprawling and chaotic capital city and managing all the competing demands of the diverse population has always been a challenge. Stuempfle found this pertinent line from an editorial from the 1910 Gazette newspaper: “Port of Spain is admittedly a difficult city to administer... a wide and well-defined boundary and something like equal treatment is the only way out of many of the present city problems.”

The colonial city was growing at a pelt and attempts to manage that did not always end in success. Carnival, in particular, with its myriad bands criss-crossing the capital city embodies the people’s spatial occupation of the city, despite attempts to create boundaries. Carnival grew out of the poor city dwellers, who had flocked in and continued to arrive daily from rural Trinidad, taking over the street parade in 1847 and by the late 1870s organising themselves into proper bands created in the barrack yards of their different neighbourhoods. The calypso tents and panyards, the open Savannah, all define the city as much as do the symbols of the State – Parliament, cathedrals, the odd mosque or temple, and other official buildings.

These essential elements of Port of Spain and the people’s culture find voice in the festival through the inclusion of traditional characters such as the Midnight Robber and his apocalyptic robber talk, through biting extempo, satirical ole mas competition and the stand-and-deliver open mic sessions. As if mirroring the intention of the festival’s programming, Stuempfle writes of Port of Spain, “While outdoor spaces offered greater possibilities for physical mobility, diverse social encounters and a multiplicity of sights and sounds, indoor venues provided contained and predictable experiences.”

Subjects of national concern are very much taken up by our writers inside the Library: an example is Naipaul’s classic political satire Suffrage of Elvira that was written sixty years ago this year. Its protagonist lives in the capital but his political constituents are the exploited Indian voters of fictional Elvira in Central Trinidad. Professor Emeritus Kenneth Ramchand, who produced a dramatised festival reading from the novel that is set around the time of the 1950 general election and still completely relevant, remarked in his presentation that, “The scientific observations contained in The Suffrage of Elvira contradict many of our analysts who see race as the defining factor in Trinidad politics. The novel recognises the influence of race, and registers that it is the mindless fall-back position. However, it casts doubt on the promotion of race as the exclusive and dominant active factor. It exposes the discontinuity between our culture and the systems and institutions that we imitatingly work, and cavalierly bend to suit our partisan purposes. The humour and comedy of the work thrive on these and other incongruities. This is why Lloyd Best described The Suffrage as the exemplary work of an artist and scientist.”

Stuempfle’s book is the work of an artist and scientist and it captures all that is at the heart of our urban culture and what has shaped the most dynamic and exciting city of the region, even as new replaces old.

Comments

"Imagining a city"