Caught in a rush

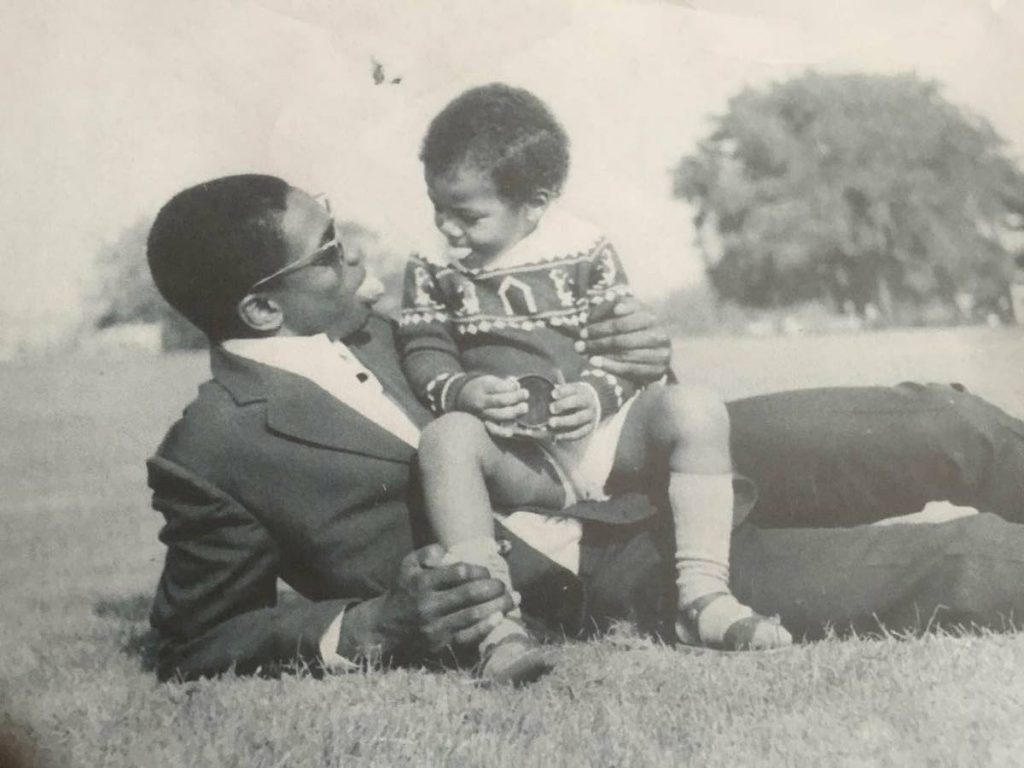

WHEN Olga and Mervin Braithwaite left the Caribbean for the UK, they envisioned a better life for themselves and their six children. The journey on British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the flight to a better life.

But the dream of that better life stood in jeopardy as many from the Windrush generation faced deportation and detention by the UK’s Home Office. However, the UK’s Prime Minister Theresa May has since apologised for this and said, according to a UK Sun April 17 article, those who came to the UK legally after World War II can stay indefinitely.

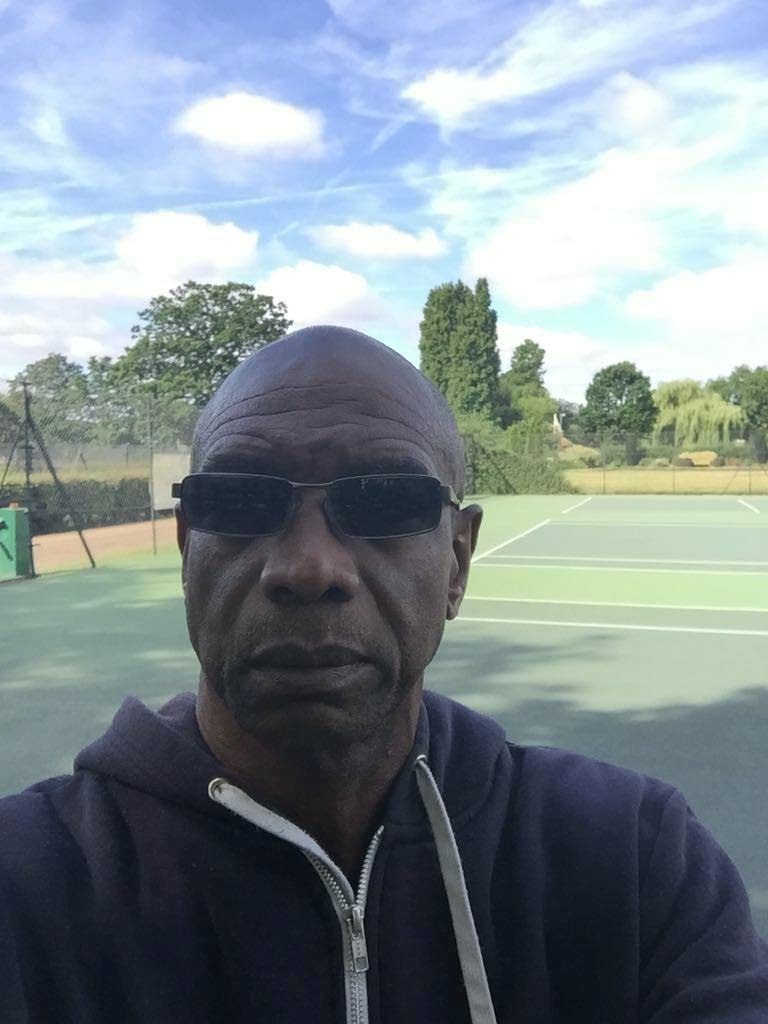

People like Michael Braithwaite, now 66, who went to the UK with their parents in the hope of a better life faced

the backlash of the then home secretary’s policy on immigration.

Braithwaite lost his job as a special-needs teaching assistant at a primary school in North London last year after a Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check flagged an irregularity with his status.

But Braithwaite received a call from the primary school to come to a meeting with its headmaster on April 23 and is hopeful he will get his job back then.

He has lived in the UK for 57 years and worked at the school for the past 15. Braithwaite lost his job on February 3 last year, but was flagged in September 2016. While Braithwaite’s story has been widely aired in the UK media,

other people from the Windrush generation also faced risk.

The Windrush generation went to the UK between 1948 and 1971 to help rebuild the country after World War II. Their name comes from the troop ship on which they voyaged from Jamaica, the Empire Windrush. An April 16 BBC article said of the current situation, “Thousands of people who arrived in the UK as children in the first wave of Commonwealth immigration face being threatened with deportation.

“Despite living and working in the UK for decades, many of the so-called Windrush generation are now being told they are here illegally because of a lack of official paperwork.”

Although an April 17 Sun article says, “Thanks to measures announced in the Commons yesterday, that threat has finally been removed,” Braithwaite wants to ensure that something like this will not happen again.

In a phone interview with Newsday, he said, “I am still confused in a lot of ways at how governments can let these things happen to people.

“As far as they are concerned, you are nothing. You have no right to be here. They are sending you back to a place, it was my home but it is not my home any more. It is my roots but this is my home.”

After applying and waiting for a biometric card (a form of UK identification) for almost two years, Braithwaite will collect it today from his solicitor. But that has already come at a cost; his job.

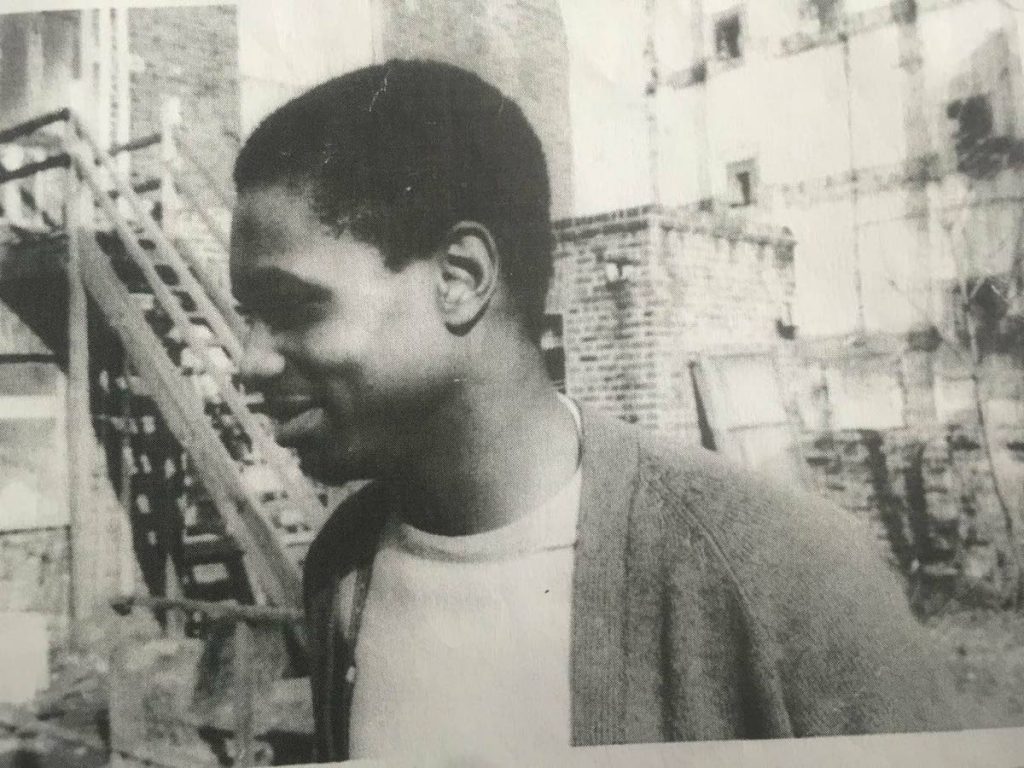

Braithwaite and his siblings were born in Fyzabad. They went with their mother to live with their grandparents in Barbados after his father went to the US.

When his father moved from America to Britain, the family also moved. Braithwaite and three of his brothers arrived in Britain in 1961. His father worked in the post office and his mother at a hospital.

The move was a shock. He recalled, “It was cold and coming in November as well. We were wearing short trousers at the particular time.”

fight continues on Page 4B

Barbados could fit into Camden, the borough he now lives in. To him, the journey was “like an endless travelling into the dark.”

He had to get used to the culture and different ways people spoke – as well as racism.

“People would want to touch you and touch your hair. They wanted to do all these things because they weren’t familiar with black kids at the time.”

He attended primary and secondary schools there. His first job was as an electrical engineer’s apprentice.

After he later went to college and got “some certificates,” he was offered a job at a north London primary school as a special-needs teaching assistant. “I have been working there for 15 years. I am a member of the team. My specialty is working with kids with behavioural problems and learning difficulties.”

He believes that as much as any other citizen he has contributed to his environment.

“I think being a black man in that environment helped. Like a role model kind of thing. Not just for my people but everyone,” he said.

He remembered the day the check on his DBS status came up and he was told by the school’s human-resource department that having indefinite leave to stay was not enough.

“I needed to have a biometric card...I was not deemed as legal.”

The school gave him a time limit to get a biometric card “or proof of who I was...I went to my solicitor and went through all the variables of the right route that suited me. Home Office took over two years to get back to me about my status.

“In the meantime I lost my job. I was borrowing money from people to keep me,” he said.

The UK is home to him, his wife, Jessica, their three children and six grandchildren.

He strongly believes that his parents, especially his father, who served in the world war, are probably “turning in their graves,” knowing that they actually helped build the country where he has been treated like an unwanted stranger.

The work of many people like his parents, he believes, has received little to no recognition in the UK.

“After the 70th anniversary of the Windrush, to have this happen and people being deported, my mom and dad would be turning in their graves. They would be disgusted with the whole situation.

“I think they would try to turn back the hands of time. They would not have come here,” he said.

Brathwaite’s story has been aired his story on UK national television and print media, and he said he also had a great team around him, which is how he was able to get his card. But others, he said, might not be as lucky as he.

UK television station Channel Four made a documentary on his situation, and soon after it aired, “The Home Office phoned the editor of Channel Four and said, ‘Michael would have his papers dealt with immediately.’ After two years of wrangling, it took that to put the situation right.”

While PM May has issued an apology for what has happened, it has not quelled Braithwaite’s feelings of disgust, heartache and pain over something he believes should never have happened. He described the apology as “half-baked.”

The only way to right this wrong, in his book, is to have recognition and something fair done “since many of them were part of the establishment.”

“I don’t want to see any underhandedness, where two years (from now) they bring back another policy. I want them to make a statement saying whoever came here as Windrush babies have a right to be here,” he said.

His biometric card means he can now work again and get on with his life.

When I came here I knew I had to work. My mom and dad worked hard and I respected that. For me I love to work and I love doing what I do.

“To have that put on me after all those years, it was a shock to my system. You have dug a hole and put me in it,” he said.

Comments

"Caught in a rush"