Dearest Jahmai

The following is columnist Debbie Jacob’s eulogy on her former YTC student Jahmai Donaldson, 26, at his funeral at San Fernando Methodist Church last Wednesday. Donaldson was one of two young men shot dead in Pleasantville on January 10.

My dearest Jahmai, I stand here today with a broken heart, knowing I can only pay tribute to you in the way you rightfully deserve by imagining you standing here beside me.

I want one more class with you. I see you so clearly almost a decade ago sitting in YTC with a group of teenage boys who changed my life in unimaginable ways. Together, today we will give everyone a lesson on taking the wrong path, going down the wrong road and finding redemption.

That first day of class I thought you would be the one to give me trouble, and I was relieved when your classmates announced in the second class, “Jahmai will not be back until further notice. He’s in lockdown.”

But Donna McDonald from the programmes’ department refused to let me go down the wrong road. She would not give up on you, and she insisted that I not abandon you either. “He’s always in trouble, but he’s a likeable boy,” she said.

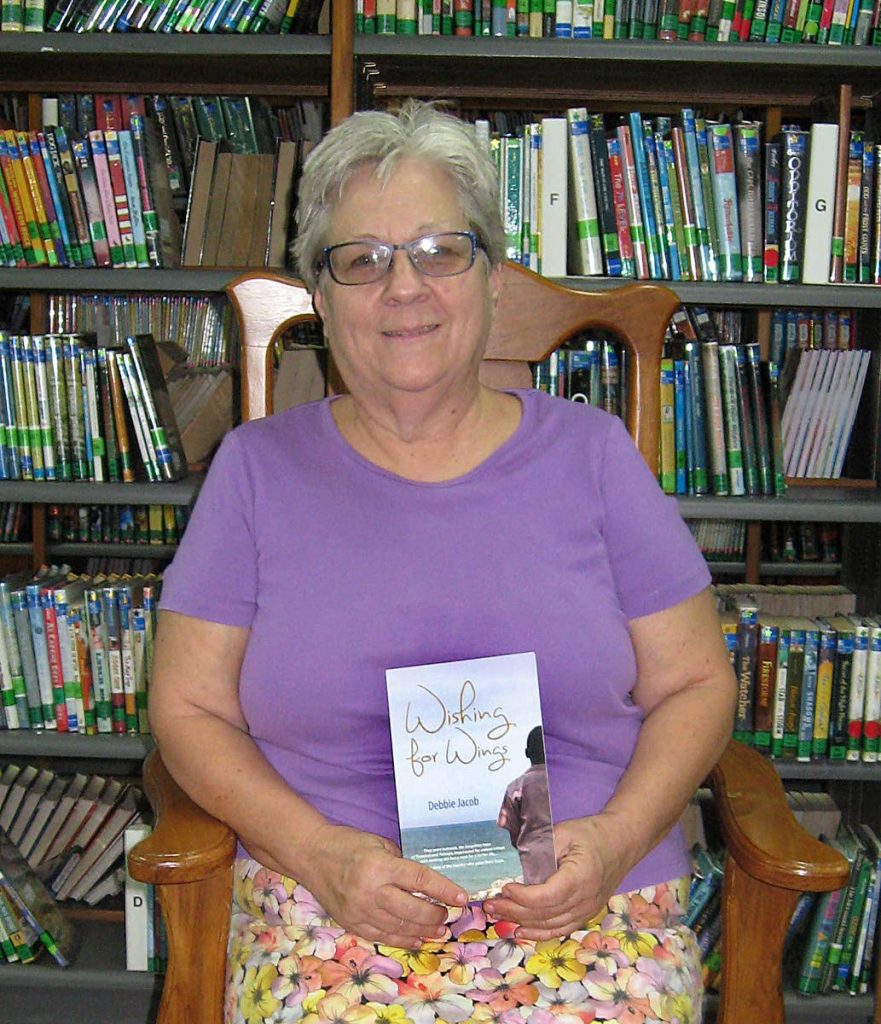

I wrote in Wishing for Wings, the story of our academic journey together, that had I succeeded in getting rid of you, it would have been the worst decision I made that year. It turns out, it would have been the worst decision of my life.

For two months, I taught you without ever seeing you. With impeccable handwriting, you completed the assignments I sent. We wrote notes to each other: You wrote: “Jahmai means “May the Lord protect.” And then, “I am always angry, and I don’t know why.” I told you, “Read. You will find the answers you are searching for.”

Later you wrote, “I am full of emotions, not only hate and anger – as some people seem to believe.”

Once you wrote, “To leave out of this essay about myself that I love my family, especially my mother Susan Grace Donaldson will be totally inconsiderate of me. I have made personal defeating choices that were in absolute defiance of her teachings and I am truly sorry. I know my heart, it is not dark, I am not evil.”

You, Jahmai, loved reading. Jane Eyre was your favourite novel.

“Reading allowed me to meet different types of people and understand how they think and feel,” you wrote. “Reading expanded my mind and helped me to accept things. Reading gave me the opportunity to go places even when I was in lockdown. In King Solomon’s Mines – I went to Africa. No one could take away my independence.

“I liked classics. I liked how the characters spoke. Their tone wasn’t modern. It came like it was before all the mess in my life. What was modern represented what I was in. Classics were a way to express some kind of comfort in the past.

I marvelled at the changes you made in your life.

“They can change,” Sterling Stewart said when he served as superintendent of YTC. “Society believes these boys are redeemable. That is why they send them here.”

But that same society asks questions every time a young man is killed. They asked me those questions: “Was he in a gang? Did he go back to his old ways? Did his past catch up with him? Was he in the wrong place at the wrong time?

“I will not entertain such questions or provide anyone in this society with a feeling of false comfort by rationalising a single murder in this country. We cannot make sense from senseless acts so that people don’t have to face their fears or do anything constructive to solve the problem of crime. Every life is important.

As we struggle to cope with this unimaginable loss I remember when you wrote: “You can get through any situation…once you are surrounded by people willing to share the pain with you so the burden, would not seem too unbearable.”

Here is what I want people to know about you, Jahmai. You were loved by your family: your mother, father and siblings: Stacy, Vaughn, Keisha, Aisha, Jahi, Ajala, Jahmila, Allan, Andre and your girlfriend, Krystal. I grew to love you as one of my own children.

You taught me to be more open-minded and to accept people for who they are – not by how society labels them. As teenagers, you and your classmates learned how to take responsibility for your actions.

In Wishing for Wings, you and your classmates put yourselves out there emotionally in ways no one should ever have to do so that you could help people understand wrong roads, responsibility, and the need for a more relevant education. Together we proved we could tackle education in daring, innovative ways. You followed my unconventional methods of teaching and got a one in CXC English language.

You all held hope for the future, but you tried to prepare me for your reality: that most of you would not live to be 30. If you have a past in Trinidad, it seems you have no future. And still you tried. You all permitted me to tell your stories in the newspaper and in Wishing for Wings with one restriction: “We don’t want pity,” you said and the class agreed. “We can handle anything: disappointment or even hate—but not pity.” You all said you wanted to do something that mattered in this life. And you did.

I want all those people who write off life in this country so casually to understand how much you accomplished, Jahmai.

You helped me prove that people can work together regardless of age, race or socio-economic status to make this country a better place. You inspired me to start The Wishing for Wings Foundation, which does work in our prisons.

Your personal stories in Wishing for Wings brought in hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants and donations from individuals, book clubs, government ministries and companies for books, classes and skill-based programmes to help young men succeed in life. Your story inspired Children’s Ark to build a library in Port of Spain Prison so inmates could discover the joys of reading and even read to their children.

In our schools, I read passages from Wishing for Wings to 150 students at a time, and you can hear a pin drop. Librarians and teachers tell me how important your stories are to students.

When I asked my friend, film maker Miquel Galofre, “How can I ever read Wishing for Wings again?” he said, “You will because someone you may never see or know or talk to will be saved by that book.”

When I told another friend how broken-hearted I felt, he said, “I have been a police officer for almost fifteen years. I’ve seen many young men who are full of potential die this way. Keep strong and continue to encourage and support them, for many have given up on them.”

Because of you, Jahmai, I will spend the rest of my life doing the work we started together as a class. I will keep trying to convince people that one of our greatest resources in this country is our young men, who are vanishing before our eyes.

Please know in spite of my grief, I have the strength to carry on because of you and my beloved boys that I wrote about: the forgotten boys of Trinidad, the outcasts who gave me the gifts of love, perseverance and hope. Your stories resonate with today’s troubled youth.

And so I end this lesson on wrong turns, wrong roads and redemption hoping the next time that someone is shot down in this country, people will not ask useless questions. Instead, ask, “What can I do to stop this violence?”

I love you, my dear, dear Jahmai. We accomplished so much together, and we will continue to do so because I know you will never leave me. You are in my heart. God bless you. May God give you wings.

Comments

"Dearest Jahmai"